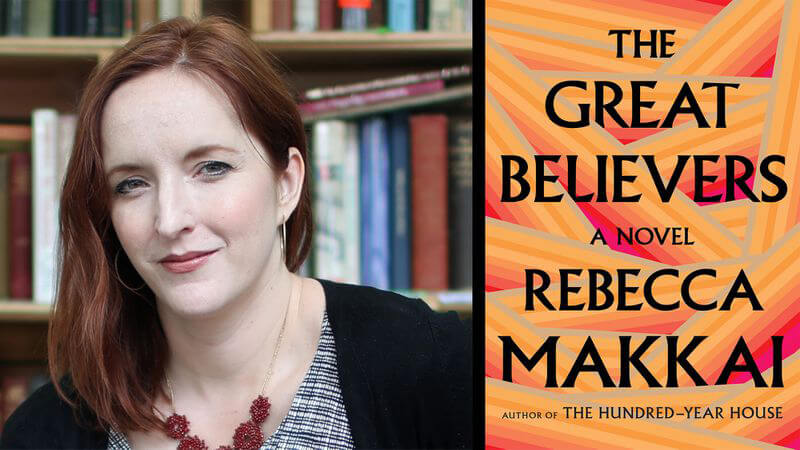

The great believers

An epigraph is a short, stand-alone quote, line or paragraph that appears at the beginning of a book. Epigraphs are most commonly a short quotation from an existing work.

Many novels (you have no doubt noticed) have an epigraph or epigraphs. They are easy to miss, like the dedication. And tempting to skip, because, if you are like me, you want to just dive into the story, no introduction or preface necessary, thank you. (I hate long introductions and prefaces.) But I do make myself read epigraphs, because they are illuminating. Not always right away, but eventually, usually.

“We were the great believers. I have never cared for any men as much as for these who felt the first springs when I did, and saw death ahead, and were reprieved—and who now walk the long stormy summer.” (F. Scott Fitzgerald)

“The world is a wonder, but the portions are small” (Rebecca Hazelton)

These are the two epigraphs that stand at the gate of Rebecca Makkai’s novel, The Great Believers. I probably read them when I first began the book, and likely I appreciated them, in an offhand way. But coming back to them after finishing the novel and after having a couple of weeks to digest it all, I see they make a good deal more sense in hindsight and have the effect now of resounding like a chord within me—not an opening chord, as I suppose these fragments are meant, but as a closing one…creating a sound that vibrates longer, maybe, than was intended, like one of those Buddhist singing bowls.

These are the two epigraphs that stand at the gate of Rebecca Makkai’s novel, The Great Believers. I probably read them when I first began the book, and likely I appreciated them, in an offhand way. But coming back to them after finishing the novel and after having a couple of weeks to digest it all, I see they make a good deal more sense in hindsight and have the effect now of resounding like a chord within me—not an opening chord, as I suppose these fragments are meant, but as a closing one…creating a sound that vibrates longer, maybe, than was intended, like one of those Buddhist singing bowls.

“Men who felt the first springs when I did, and saw death ahead…” “the world is a wonder, but the portions are small”

The Great Believers is a novel that takes place in two different times—the 1980s and 30 years later; a double narrative, with some overlapping characters. The story begins with Yale Tishman and his partner, Charlie, making their way to a party at their friend Richard’s house. The event is a gathering of friends following the funeral of Nico, a young man who “had made it clear there was to be a party” before he passed away. “If I get to hang out as a ghost, you think I wanna see sobbing?” he had said. “I’ll haunt you. You sit there crying, I’ll throw a lamp across the room, okay?” (He goes on to say something about a poker and what he will do with it if there is too much public display of sadness, but because this is a family paper, I won’t include it.) Nico’s friends and associates had spent three weeks mourning, “and now Richard’s house brimmed with forced festivity.” Julian, Teddy, Nico’s sister Fiona, Nico’s lover Terrence…people mingled and flooded in, while the house loudened by the minute. “Two very pretty, very young men circulated with trays of little quiches and stuffed mushrooms and deviled eggs,” the book goes on (I am just gathering fragments here, to give you an idea…).

“In any case,” the novel goes on, “this was infinitely better than that strange and dishonest vigil last night. The church had smelled nicely of incense, but otherwise there was little about it Nico would have liked. ‘He wouldn’t be caught dead here,’ Charlie had said, and then he’d heard himself and tried to laugh.”

“Nico’s illness had been sudden, immediately debilitating—first a few days of what had seemed like just shingles, but then, a month later moon-high fevers and dementia.”

I had no idea what this book was about when I first began it. It was a book club pick and a total mystery. All I knew was the title, the author and that I had only a couple of days to read it (not enough, as it turns out). I had no idea how it would take me back to the 80s and the whole AIDS epidemic, a time when one by one young men in our midst were falling ill and dying, no cure in sight.

I remember the time well. Or now I do. I hadn’t forgotten it, I don’t think I could ever forget it, but I hadn’t really thought about it for a while. But this book stirred my memory, big time. It all happened back when I was living in Miami Beach. I had heard rumors of a disease that affected the immune system and was spread by unprotected sex, blood transfusions and needles And then suddenly, like a Florida rainstorm, it was upon us. Out of the blue, young, young friends of my husband and me were falling ill, developing rashes, coughs, lesions, blindness and—surreally—dying. People our age and younger; people who had just been living full, fit active lives. I remember visiting them in hospitals: Frank, Jeremiah, George, George, Tim—young men who had been so beautiful, healthy, fit and spirited…now crippled, diminished, fading, gone. I remember haunting, uncomfortable interactions with friends, one day so vividly alive, the next: sinewy, pale, tethered to IVs in hospital gowns—one sitting in a chair, turning his head, unable to see us because the disease had taken his sight—so many trying to make light of the situation, to find some humor in the horror to ease their visitors’ sorrow and shock. I remember funeral after funeral, remember throwing rose petals in the ocean, remember a mother throwing herself into her son’s coffin, sobbing, overcome. This book took me back to so many memories and aspects of that time. It has helped me remember and honor those lives lost—both the lives of people I knew and the lives of so many thousands I didn’t—and to recall also the tragic and woefully inadequate response of the government to the carnage of the AIDS epidemic, which is touched upon also in this book.

I found this a powerful read. Very well written. I felt I really knew the characters, and not a one struck me as a caricature. Each has his/her idiosyncrasies and motivations, ways of speaking, styles and nuances of humor and self-reflection. The plot is interesting, and there’s a lot going on. I didn’t want to put it down, but dreaded finishing it, too. Some books are just that way.

Lots of texture and complexity here, but not, in any way, overwhelming. There is a lost person who someone is desperately trying to find. There is relationship drama. Betrayal. Disappointment. Hope. Love. There is some political activism, and a coup involving a collection of 1920s paintings that happen to be in the possession of an old woman who was once an artist’s model in Paris during the time of Modigliani. There is a fleet of interesting, amusing, distinctive characters. There is humor and tragedy both. I loved it.

And not that this has anything much to do with the book, a strange thing happened while I was reading it. I will tell you, quickly. So, on Jan. 28, I saw on Facebook a photograph of the Space Shuttle Challenger exploding midair spiraling thick smoke, along with a short tribute explaining that Jan. 28, 2022, was the 36th anniversary of the tragic explosion. Meanwhile, I was midway through reading The Great Believers, hustling in hopes that I could finish it before book club. So, I saw the photo on Facebook, then went back to reading. In less than an hour, I came upon a scene in the book wherein one of the characters is in a hotel room and turns on the TV, and sees the Challenger Space Shuttle explode. Jan. 28, 1986.

Weird, right?

Anyway, to bring this all full circle, let’s get back to the epigraphs…and the idea of “men who felt the first springs when I did, and saw death ahead…” coupled with a reminder of the brevity of life: “the world is a wonder, but the portions are small”—so perfect for that time, those lives, those relationships—so perfect for this very good book, which the Chicago Tribune describes as “remarkably alive despite all the loss it encompasses.”

Hope you are all well and enjoying the snow, enjoying life.