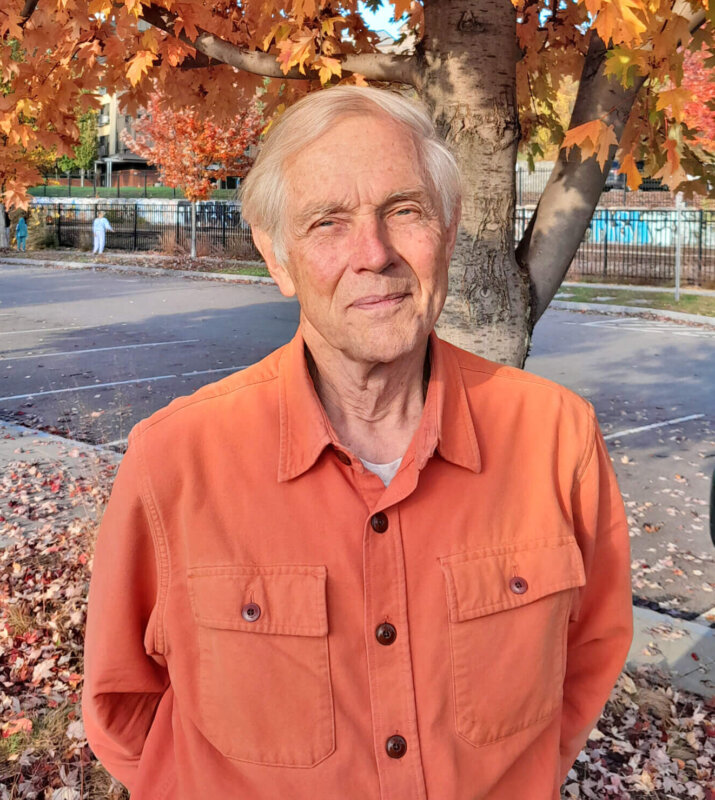

Net zero means a lot to this sustainability advocate

After over 40 years in the Baltimore area, Wolfger Schneider was looking for a new home when he retired in 2010.

He took a two-month trip across the U.S. and Canada. He was familiar with Vermont from previous hiking and skiing trips and thought the state was aligned with his values.

Schneider decided to settle in Charlotte and picked Champlain Valley Co-Housing for this newest phase of his life.

“I didn’t want to live in a 55-plus community,” he said. “I enjoy the voices of children and the company of people of all ages, so I thought this was the right amount of age variety.”

Schneider almost immediately immersed himself in the causes he holds dear, joining a Montpelier-based organization called Better (not bigger) Vermont. Originally named Vermonters for Sustainable Population, the non-profit has been around since the early 2000s. In 2015, Schneider became the organization’s president. He is also a long-time member of Sustainable Charlotte and two years ago, he joined the Charlotte Energy Committee.

Schneider is not new to sustainability issues. He has been involved in environmental organizations with sustainability emphases since reading Donella Meadows’ 1972 book “Limits to Growth” and was part of a group in Baltimore which was affiliated with the Sierra Club.

One of the goals of Better (not bigger) Vermont is to switch from relying on the gross national product as an indicator of a country’s health to a measurement that does not value growth above other factors. Better (not bigger) Vermont is also in the process of trying to create a Vermont Happiness Index.

The main concern of Better (not bigger) Vermont is sustainability. In 2013, the organization issued a report indicating that the state was close to sustainability, but Schneider said we are slightly above that watermark at this junction with food production costs and energy consumption the major issues preventing the state from reaching its goals.

“Our impact on the environment is a product of our standard of living and our population,” Schneider said.

Schneider’s environmental concerns are addressed on a personal, as well as organizational level. He lives in a net-zero home that was built using insulated concrete forms which he described as huge, thick, Lego-like blocks with a center cavity filled with concrete and rebar. The resulting product is a good insulator and prevents rapid temperate changes although Schnieder admits that the upfront energy costs are high.

For four decades, Schneider worked in the applied physics lab at Johns Hopkins University, in areas as diverse as the defense industry, spacecraft design and biomedical research.

“It was rewarding,” he said. “It was a challenge to be creating solutions for different projects.”

In addition to his committee work and his position as president of Better (not bigger) Vermont, Schneider has been involved in hands on projects like Sustainable Charlotte’s Repair Cafes and Window Dressers, a volunteer organization that produces and installs low-cost insulating window inserts. He is the head of operations and management at his co-housing community and enjoys gardening and reaping the benefits of backyard chickens.

Schneider isn’t overly optimistic about the state of the planet because he doesn’t see much progress toward sustainability.

“There is a lot of denial about things like global warming and our impact on the environment,” he said. “Vermonters are an exception in being more on board with these issues than the rest of the country.”

Schneider is fine with that because he believes the future is based on local actions including those involving agriculture. He thinks farming is becoming more and more significant because food is the most important energy source. He does worry about a group called the Vermont Futures Project which has a goal of increasing Vermont’s population by 1.8 percent per year to reach 802,000 people by 2035, something that Better (not bigger) Vermont opposes.

“I think we should honor what we currently have in Vermont in terms of natural resources,” Schneider said. “We should do our best to protect them because in the end, we are all dependent on nature and its healthy state.”