Don’t slap them, count them

CCS students make a mission out of mosquitoes

CCS students make a mission out of mosquitoes

The mention of NASA brings to mind things hurtling through the air—for third graders at Charlotte Central School, those flying objects are mosquitoes, and their mission is to figure out when those pesky summertime visitors are going to show up. As part of The Globe Program, Mission Mosquito is a citizen science project that helps NASA scientists identify patterns in mosquito growth and infectious disease around the country.

According to The Globe Program’s web site, “NASA scientists are interested in understanding how changing weather patterns, extreme weather events, insect ecology and human behavior affect the range, frequency and distribution of mosquito vectors that can potentially cause disease.” Third grade students in Leslie Thayer and Ena Jesset’s classes worked with Champlain Valley School District Director of Digital Learning and Communication Allan Miller to collect data and create mosquito traps to figure out when mosquito larvae were going to hatch in Charlotte.

Students placed traps in different locations around the school grounds—some swampier and more dramatic to walk to than others—and monitored the temperature of the water in their traps over a series of weeks. Students also noted weather conditions like sun, cloud cover, wind speed, and maximum and minimum air and soil temperatures.

On Monday, June 10, students brought clipboards with their Beaufort scientific observation charts outside to inspect their mosquito traps and collect data. Third grader Story Holmes, heading out into the hot sun, said, “I hope there’s larva or eggs,” and his classmate Mavis Carr noted that the hot weather over the weekend was an encouraging sign that things could be developing in the larvae department.

Though students didn’t find any in their traps that day—a cold spring could be the culprit—Miller said, “Not finding any is just as valuable as finding them. NASA wants to know where they are, and where they are not.”

Before the end of the week, students will upload their data using an app developed specifically for the project, and their information will be compiled with that of other schools from around the country to create a big picture for NASA scientists of where mosquitoes are hatching and compare that to where infectious diseases from mosquitoes are spreading quickly.

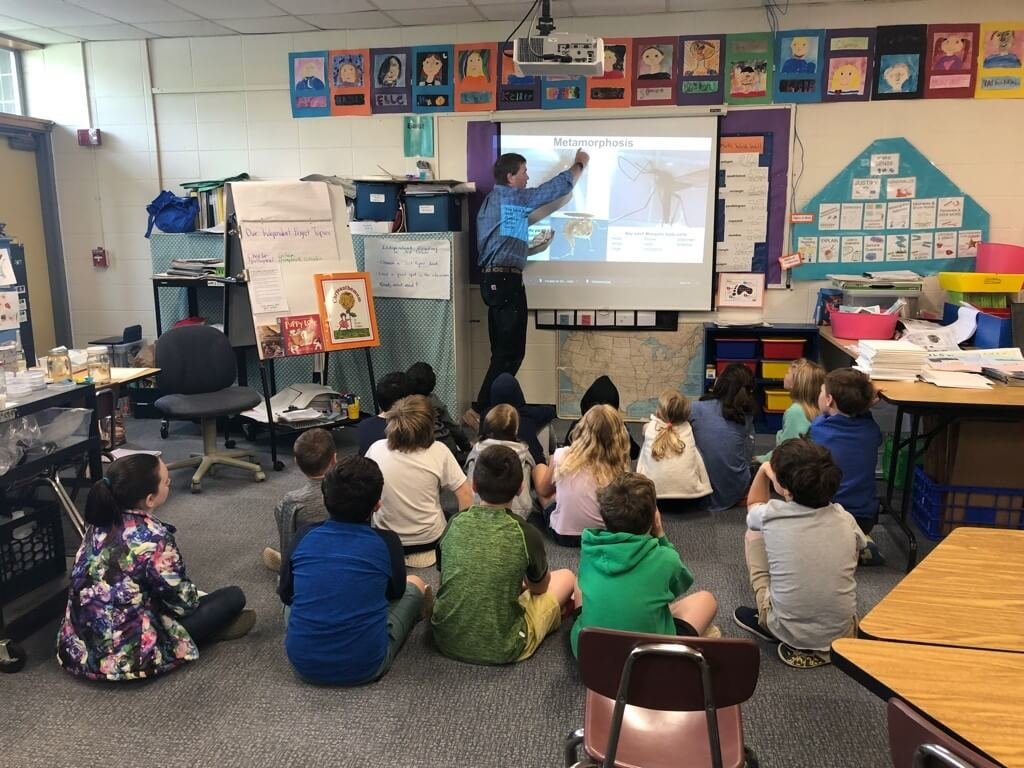

Interdisciplinary classroom work was part of the project as well. Students used hand lenses at their desks to inspect mosquitoes at various stages of development and then created scientific drawings, labeling the parts of the insects.

Interdisciplinary classroom work was part of the project as well. Students used hand lenses at their desks to inspect mosquitoes at various stages of development and then created scientific drawings, labeling the parts of the insects.

Students also video conferenced with scientists in London who are working on the Mission Mosquito project, who reminded them to work together, as a team, to get the best and most accurate data. Jesset reminded her wiggly group of nine-year-old scientists of this fact as they worked during the afternoon on one of the last days of the school year.

Though no mosquito larvae have turned up yet, a few more sunny days could do the trick, students said. “We want eggs to hatch before school ends,” Holmes said. That would mean just in time for those mosquitoes to hit a barbecue or a graduation party this weekend.