Celebrating only Revolutionary War battle fought in VT

The Battle of Hubbardton may be more significant in our country’s founding than Independence Day. On July 4, 1776, or Independence Day, a document was supposedly signed explaining the resolution for the separation from Britain that Congress had approved two days earlier on July 2.

Even whether July 4 is when the formal Declaration of Independence was signed, after it had been hastily written to explain the colonists’ reasons for giving Britain the boot, is in doubt. Nowadays, many historians say that the Declaration of Independence was actually signed a month later on Aug. 2.

However, a date a year later — July 7, 1777 — may be an even more crucial date in the formation of our country. On that day, the Americans lost a battle but, as subsequent events turned out, won the Revolutionary War. The successful drive to independence may have begun at Hubbardton.

Yugin Roh at 10 months was the youngest reenactor, dressed in her historically accurate clothes.

On Saturday and Sunday, July 12 and 13, about 150 reenactors relived that monumental battle on the site in Hubbardton, and with the advantage of hindsight, shared stories of the consequences of the fateful engagement, the only battle of the Revolutionary War fought entirely in Vermont.

When Lexington and Concord happened, initiating armed confrontation with the British, Ethan Allen saw an opportunity to sustain Vermont property rights. He knew that Forts Ticonderoga and Crown Point were weak and poorly garrisoned, and felt that if he captured the forts in the name of the Continental Congress, Grants leaders could leverage the victories to achieve independence.

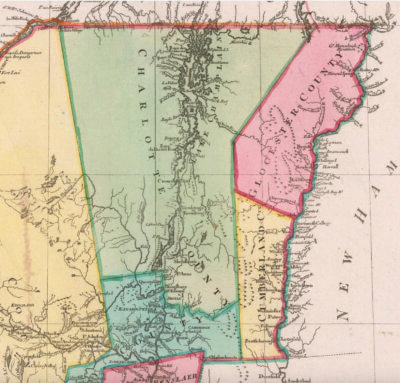

By 1775, the people of the 138 towns, in what was known then as the Hampshire Grants but came to be known as Vermont, had been resisting the Royal Colony of New York’s claims on their land.

These westernmost grants were the wild frontier in those days; the people interested in settling tended to be independent-minded miscreants and rebellious misfits who came north in family groups to hack out a homestead in the wilderness. Most had a sour relationship with the established Congregationalist churches that controlled much of life in their communities. One historian commented that when the settlers moved north they failed to pack religion among their belongings. What they did bring was an egalitarianism that was remarkable for its time.

Ethan Allen, a born rebel, had been kicked out of two towns in his native Connecticut, and following the premature death of his father, had assumed the responsibility for the futures of all his siblings and his widowed mother. He felt that land speculation in the Hampshire Grants was his best chance to establish family wealth; but when he and his extended family arrived in Arlington in the Grants, he was met with a controversy over the land titles.

For more than a decade, Hampshire Grants leaders had been confronting escalating altercations with the New York authorities. New York claimed all of what would become our state, basing their claims on a vague 1664 charter. Despite a stinging rebuke from Lord Shelburne on behalf of George III in 1767 that stated the King himself had sustained the Grants charters, and no colonial governor had the authority to override it, the New York administration continued to become more belligerent and aggressive in attempts to dispossess the people of the Grants.

If they were going to strike a blow for independence as a separate political entity, they would have to call themselves something. Initially they decided on “New Connecticut,” but were advised that the name was already taken by an area in western Pennsylvania. Allen’s good friend and volunteer military surgeon, Dr. Thomas Young, is sometimes credited with suggesting the territory’s name be adapted from the French words for “green mountain” (“verde mont”), and the Green Mountain Boys went to war under the banner of “Vermont.”

With the bloodless capture of both forts, Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys became household names throughout the colonies. The forts yielded more than 130 cannons, which, at the direction of Gen. George Washington, were dragged overland by Henry Knox to the heights above Boston to threaten the British occupation there. With British troops and forts no longer along Lake Champlain and with the withdrawal of the British from Boston, Britain’s influence in New England was gone. It was a big deal.

And Britain chafed to regain what had been lost.

The leaders of Vermont, believing we had demonstrated both our independence and our competency, petitioned for the recognition to the Continental Congress that would sustain our property rights, but were basically told to go pound sand and accept New York sovereignty. When Vermont declined, we were considered in rebellion, not only against our neighboring states of New Hampshire and New York, but now also against the fledgling United States.

Nonetheless, Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys found themselves on the battlefield fighting with New Englanders against the British.

Gen. John Burgoyne led a large army south from Canada in 1777 to drive a wedge between the colonies and isolate New England. The Vermonters recognized the threat to our region and begged Congress to provide troops for our defense, which Congress summarily rejected.

Burgoyne outflanked the colonial troops that garrisoned Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence, and on the morning of July 6, 1777, the Continentals were forced to beat a hasty withdrawal, leaving Vermont open to invasion and almost defenseless.

Closely pursued by regiments under the command of arguably Burgoyne’s finest field commander, Simon Fraser, the British caught up with the exhausted rear guard of the colonial troops at Hubbardton on July 7, 1777.

These troops consisted primarily of Green Mountain Boys and militia from New Hampshire and Massachusetts under the command of Seth Warner and Ebenezer Francis, who fought Fraser’s men to a standstill in a fierce battle. Casualties were high on both sides. With the subsequent retreat of Warner’s men, Burgoyne could claim a victory.

However, the tenacity of the untrained Grants settlers and regional militia was a blow to British confidence. The Continentals’ battle strategy shifted to rear-guard action, covering the retreat. This was called by some of the reenactors the greatest rear-guard action in history.

The bulk of the soldiers managed to get away to Saratoga where they contributed to Burgonye’s defeat and surrender on Oct. 17, 1777.

Historians have suggested that Burgonye’s surrrender at Saratoga may be the most significant turning point of the war. Besides being a great morale boost, this victory helped to convince France to join the war on the Continentals’ side, which meant a boon in money, soldiers and munitions, but which also meant that Britain was now engaged in a worldwide naval war.

(Dan Cole is president of the Charlotte Historical Society and a volunteer guide and researcher at the Ethan Allen Homestead in Burlington.)

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair