Quench melancholy of time by staying alert to nature

Tonight, I am feeling reflective and somewhat consumed by introspection and melancholy. I am looking back on my life while Merle Haggard is singing to me: “Are the Good Times Really Over for Good?” on livestream on my laptop.

I think back on the time I spent with my father. It seems like the older I get, the more nostalgic I become. Memories flood back to me regularly and they warp my thinking that the “good times really are over for good.”

My friend Doug catches me doing this and calls me out with his wisdom informing me that this is called “euphoric recall.” He’s usually right about it. But Doug is also much younger than me, so I’m not sure he’ll be able to maintain that enlightened state when he’s my age.

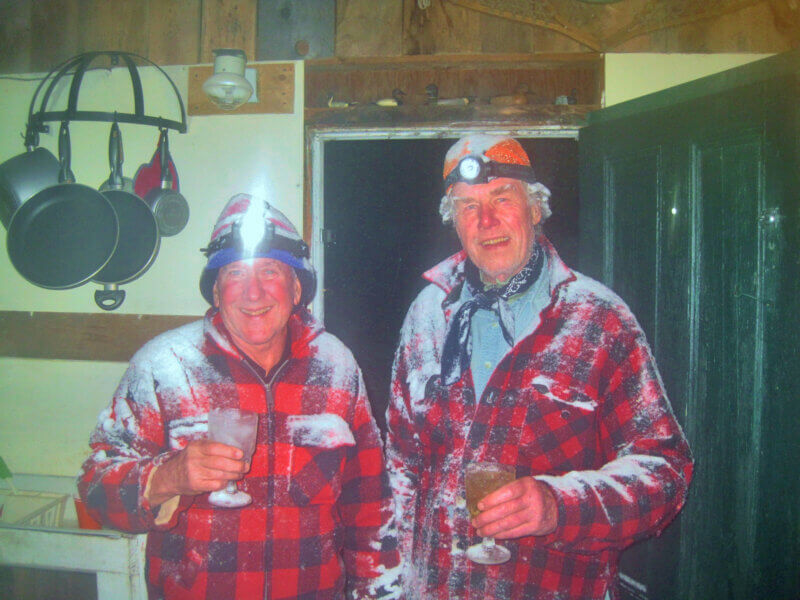

My dear friend Hank Hagar called me last night, and we spiraled into a joyful vortex of reminiscence about days past at deer camp.

There was the time that Kennedy Snow slipped and fell on his back in front of the camp, and when we leaned over to see if he was alright, he proudly stated that he hadn’t spilled a drop of his beverage.

There was one night when I sat up in my bunk because I heard someone speaking in the middle of the night. I peered down to the dining area and there was the proprietor, Johnny McDonough, talking to a mouse that was sitting on his haunches listening to Johnny talk from his rickety red chair in front of the wood stove. The mouse knew that Johnny meant no harm to him as John told him “You know, you little #$%%&^ someday this will all be yours.”

Memories of squirrel hunting in Pennsylvania where I spent my early adolescence haunt me. At the time it felt like unadulterated teenage angst. But once my father bought me that old Glenfield .22 and, having passed the Hunter Education course, that badge meant that the world was my oyster. Into the woods I would disappear trying to imitate a squirrel’s chipping and scolding vocalizations.

My father was a stalwart workaholic, which is probably why I was a carefree, lazy and undisciplined student. The only education I wanted was the one I got from my time outdoors. I was so difficult to reign in that when my family talked about moving to Switzerland, for my father’s business, I told them that, at the wise old age of 16 years, I would be moving to Vermont. I knew early on where my soul needed to be.

Failing in public school in a steel mill town that worshiped football and manufactured sophomores made from the Steel City’s iron ore and stood 6 feet 2 inches, weighed 250 pounds and were being scouted by NFL teams while still in high school, this was no place for me.

When I tried out for junior varsity, the hazing program was simple. I had to hold up this big cloth wrapped punching bag roughly 6 feet high and weighing around 200 pounds while these genetically abnormal beasts came running at me.

The coach’s instructions were “try to stop them.” After being pummeled several times, I realized that I did not fit in. I wanted to live with my lungs fully functional.

I think my soul left me after the third time. I was left gasping for air on the ground. I was somewhere in the Great White North, tracking monster bucks. I began to daydream of moving north. I imagined hunting the big bucks that Field and Stream and Outdoor Life wrote about, where the legendary Benoit family lived and must be somewhere north of the 45th parallel.

I applied to Vermont Academy under the premise that a good portion of the curriculum would be performed outdoors. Finally, I found where I belonged. So much so, that I was able to convince my parents that we needed to move here. We moved to Stowe, and I learned to ski and hunt the big woods.

Again, here I wasn’t popular, because I was “just another flatlander coming in to change the place.” But what happened was that my father and I finally found our connection. We built a tree stand made of large pieces of lumber on the back side of Round Top.

On opening morning of rifle season, I fell asleep in the stand, 30 feet up in the trees. My father, who was sitting beside me, woke me and whispered, “There’s a buck! Take ‘em, Bradley!”

I replied. “You take him. He’s on your side.”

“Nope. Just crawl over me and shoot it.”

The old Winchester Model 94 30-30 rang out, echoing through the valley. This was my first deer.

I remember the long drag back to our house a mile away. I remember everything like it was yesterday. It was snowing and the air smelled fresh and clean as we dragged the fork horn past the neighbor’s barn. It was lit up inside by a yellow glow where the cows were being fed. I could smell the manure, and instead of a flatlander’s reaction, I inhaled as if it were some life-affirming, earthly fragrance.

John Denver was singing “Back Home Again” on the radio in the barn. The cows seemed to be enjoying it. The feeling of accomplishment for the extraordinary effort that we had put into this adventure bonded us, and I finally understood my father as he must have been as a child in central Pennsylvannia.

Years began to pass more rapidly, and I accumulated more and more memories. Some by myself. Some with friends.

With my father gone for several years and witnessing friends pass on or make life choices that took us in different directions, the acknowledgment of the insensitive way in which time passes now that I am in my 60s seems like the present rarely measures up to the euphoric recall of my past.

For me, when I sit on a pickle bucket out on the ice, staring down a white cylindrical shaft, I grieve for the friends I’ve lost and the humor of past deer camp members. How can anything live up to the memories of my days already spent outdoors?

For me, the cruel beverage of melancholy for the time that has passed can only be quenched by one thing. Get back on the ice. Get back in the woods. Listen to a squirrel as he chips away on an acorn in the treetops, watch for the slightest movement on a distant hillside during the last few minutes of legal shooting time or notice the tiniest pulse of the rod tip bowing down to the hole in the ice, is all that I have now.

And now, knowing myself as I do, the meaning of any moment is in the practice of staying alert to all sounds, all movement, every wind direction, the smell of fresh acorns and butternuts, or the smell of fresh cut hay and the distant honking of geese. This is the meaning and purpose of my good fortune to still be walking on this planet.

One day, I, too, will become a memory, and I hope that when people hear the honking of geese, the smell of fresh manure or feel the cold North wind stinging their face on their boat ride to the duck blind, I will be there. It is where I belong. Now and then.

(Bradley Carleton is executive director of Sacred Hunter.org, a privately owned limited liability corporation that seeks to educate the public on the spiritual connection of man to nature through hunting, fishing and foraging.)