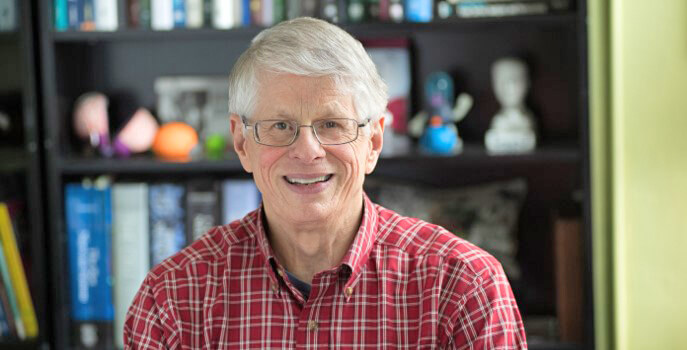

Rex Forehand: Helping parents help their own children

Rex Forehand has made a career out of training psychologists, but he’s written a book that can help those in need of their services do some of their work by themselves.

This month, the fourth edition of his book, “Parenting the Strong-Willed Child: The Clinically Proven Five-Week Program for Parents of Two- to Six-Year-Olds,” became available.

The book stems from an intervention program Forehand helped develop for therapists working in a clinical setting with young children with behavioral problems. Aided by Nicholas Long, a colleague from the University of Arkansas Medical School, Forehand turned the program into one that parents could do on their own without clinical intervention. For the fourth edition of the book, the duo teamed up with a third author, Deborah Jones of the University of North Carolina. The new edition contains suggestions for parents on how they should de-stress themselves before dealing with their children and recommends that they reach out for help with their own issues.

Psychology wasn’t Forehand’s first choice for a career. An interest in individuals with developmental disabilities led him to pre-med studies, but he didn’t think that was his strength. He tried social work but found the field too nebulous for his liking. Although he is a licensed psychologist, he has always been drawn to the academic side of the field and is happy to have a role in guiding students in the profession.

Forehand’s primary interest is in family stress and how that affects children’s psycho-social adjustment. It stems from some post-doctoral work he did at the Oregon Health and Science University where he worked with a woman who ran intervention programs.

“My concern has always been for children,” he said, “so if I can help parents help their own children, that’s even better.”

Forehand and his wife are from southern Alabama, and he spent 31 years teaching at the University of Georgia. Despite those Southern roots, Forehand’s wife hated the heat and whenever she saw job openings in New England, she would prod him to apply. Twenty-one years ago, he did just that, applying for a job at the University of Vermont where he taught until the end of 2022.

Forehand said his hardest adjustment to life in Vermont wasn’t the cold weather, but the fact that it gets dark so early in the winter months. “After the first year,” he said, “we just decided to put on our pj’s and get ready for bed early.”

Forehand has served as a member of 10 different editorial boards. In addition to his teaching and writing, he spent four years as the administrator of the Vermont Biomedical Research Network which used to be known as the Vermont Genetics Network.

Administrative work isn’t new to Forehand, who was the director of an institute at the University of Georgia and served as the director of clinical training in the University of Vermont Psychology Department. The Vermont Biomedical Research Network is funded by an almost $20 million grant, renewable every five years, with a mission of building a culture to promote biomedical research infrastructure at four-year colleges in Vermont.

Forehand is currently involved in a project to develop an on-line program for parents of young behavior-disordered children that therapists can use. The program would be available through mental health centers in Vermont to teach those therapists how to work with families.

“I’m not a technology person, so it’s a great learning experience to be able to deal with technology and the mental health system,” Forehand said. “That keeps me alive and going.”

Forehand noted that sometimes professionals may change their minds about working in some of the more rural mental health centers in Vermont, and when that happens, the training has been wasted. By providing on-line training, he’s hoping to prevent that loss of talent, time and money.

“I think it’s important to reach out to mental health centers and assist them,” he said.

Although psychologists often work with people in difficult situations, Forehand said the key to not getting depressed as a professional is to always look forward. “You have to think about how you can help that family,” he said. “Getting yourself bogged down in their problems is not the way to help people.”

Not surprisingly, Forehand finds his work extremely rewarding. He feels he can have a greater influence on individuals and families by training others to go out and do that work.

“It’s a profession I’d recommend,” he said. “It’s hard to get into these days but it’s one where you feel like you’re always giving something and also getting something back.”

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Bill Regan, Chair, Board of Directors