Books on boats, Magic 8 Balls, Sneetches and strings

Years ago, when my daughter was about 8 years old, a small group of friends and I gathered one winter afternoon at Village Wine and Coffee in Shelburne, where (some of you might remember this) there was — situated on the counter near where you ordered your coffee or tea or hot chocolate or scone — a Magic 8 Ball. You know the kind. With the little plexiglass window beyond which floats a series of answers written on a little white die suspended in a purplish-bluish-colored fluid: “NOT NOW” … ”YES” … ”NO” … ”REPLY HAZY, TRY AGAIN” … ”MAYBE,” and so on.

The device, I discovered recently, has its origin in 1946 with an idea generated by a man named Alfred Carter, son of a clairvoyant, fortune-telling mother living in Cincinnati who claimed she could commune with ghosts.

Anyway, a bunch of us were there at the coffee shop with our kids, and at one point I glanced over and spotted one of my daughter’s friends, a precocious, energetic child named Marley, clutching the Magic 8 Ball in her hands, a gaggle of her 8-year-old friends, one of whom was my daughter, huddled eagerly around her.

“Harmless,” I must have thought to myself at the time, turning back to my friends, my latte and our conversation. Then I heard Marley say, in a rather loud and not undramatic voice, “Tell me when I’m going to die!” Involuntarily, my friend Maria’s teenage daughter, Alessi, and I leapt to our feet and lunged for the shiny black sphere in Marley’s clutches, thus successfully disrupting the little congregation and ending the dreadful inquiry on the spot.

Alessi and I have reminisced about this many times in the years since. To my knowledge, everyone who was present is still alive.

This memory came back to me recently as I read “The Measure” by Nikki Erlick, which takes on this idea of what-if-we-knew-when-we-were-going-to-die in a work of fiction. Though perhaps not one of the great literary achievements of our decade, this book is interesting and compelling, but I don’t want to tell you too much about it, because part of the fun of reading it was the surprise of it, the not-knowing-what-is-going-to-happen-next-ness of it. Let’s just say, what if one morning you woke up and went to let your dogs out the front door and there on the stoop was a little wooden box, inside which was a length of string — and it turns out not only your neighbors down the street found identical boxes on their stoops, but everyone on the whole planet over the age of 22 experienced the same thing? Even homeless people. Even people living out in the desert in tents. Everyone. And turns out the length of the string in those boxes has everything to do with the question little Marley so boldly, unwittingly and recklessly asked that winter day at the coffee shop.

“The Measure” spotlights the stories of a small handful of characters whose lives interconnect over time. What they do with their boxes. What they do with their strings. What they do with their dreams and their relationships. And what they do with their knowledge (or ability to know) of their own mortality.

Reading this novel took me back to a story I read a long time ago, back when I was younger even than coffee-shop Marley, “The Sneetches” by Dr. Seuss (published in 1961) about a community of creatures that look a bit like yellow birds, but are far more interesting and inventive than that, of course, because Dr. Seuss is a genius.

Some of the Sneetches have a green star on their bellies, some do not, and at the start of the story, the Sneetches who have a green star lord it over those who don’t. Such is life, for a time, in the Sneetch world, until a wise guy named Sylvester McMonkey McBean shows up in town with his Star-On machine, which, for only three dollars, can give any Sneetch lacking a green star on their belly just what they need to improve their status in the Sneetch community: a green star. To make a not-so-very-long story short, the tale is brilliant and all about the silliness and arbitrariness of prejudice and discrimination. According to Seuss himself, it is a satire of discrimination between races and cultures, inspired by his opposition to antisemitism.

But in the case of the world described in “The Measure,” it is not race or religion or financial standing or green stars on one’s abdomen that generates prejudice and discrimination, it is the length of the piece of string you happened to find outside your door.

I really enjoyed the book, which looks at some of the micro (personal) and macro (social, political) implications of the string situation, and deftly brings it all home in the end. Uplifting and enjoyable. Thought-provoking. I do recommend it.

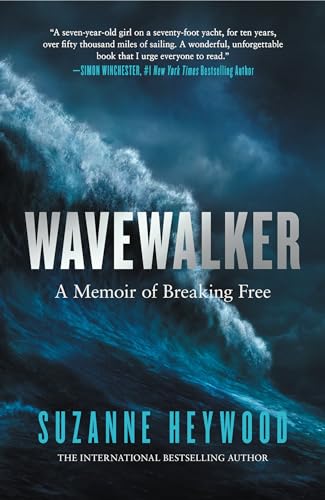

Another book I read recently and found riveting is Suzanne Heywood’s “Wavewalker: A Memoir of Breaking Free.” I don’t know about you, but I vaguely remember, back when I was in high school, news reports of a family that was sailing the world. I didn’t know much about it at the time and didn’t take time to follow the story beyond its most basic headlines, but my memory is that, caught up in the difficulties, intricacies and complexities of being a teenager in the 70s, the idea of escaping with one’s family and avoiding the world beyond the ocean sounded rather appealing.

Well, think again, Earlier Self, because it wasn’t all sunshine and roses.

Heywood begins, “This book tells the story of my childhood, during which I spent a decade sailing around the world. It takes place on a boat, which sometimes followed the route of Captain Cook’s epic third voyage, but it is more about the excitement, frustration and heartbreak of growing up in extraordinary circumstances than it is about that famous captain or his search for the North-West Passage. I spent a long time getting ready to tell this tale.”

Peppered with excerpts from the journals of Captain James Cook, a British explorer, naval officer and cartographer (1728-1779), who made three famous voyages in the Pacific Ocean, where he achieved the first recorded European contact with the east coast of Australia and the Hawaiian Islands, as well as the first recorded circumnavigation of New Zealand and the occasional quote from William Shakespeare, this book begins in Warwick, England, in 1975, when the author was 6 years old. It speaks of the familiar rhythm of waking up, having a brother, eating cereal, going to school, eating dinner, her parents’ casual kitchen conversations.

“I was used to the rhythm,” Heywood writes, “I liked it and thought it would never change. Then one morning over breakfast, my father announced that we were going to sail around the world.”

The starkly honest, compelling account that follows this paternal declaration takes the reader, basically, all over the place. England, Brazil, Ilha Grande, Tristan da Cunha, South Africa, Ile Amsterdam in the Indian Ocean, Australia, the Coral Sea, the Solomon Islands, New Hebrides, Ile-des-Pins, Fiji, Tonga. I now feel as though I have visited all those places and spent days, weeks, months, years with young Heywood sailing in fair weather and foul (and in some cases, we’re talking seriously foul), constantly referring to the little maps at the beginnings of some of the chapters, tracing with my finger the broken lines detailing the route of the 30-ton, 70-foot-long wooden-hulled Wavewalker, as it makes its way from port to port. The plan was to sail for three years. The reality was more like 10, for Suzanne, at least, who finally managed to extricate herself from a life at sea and get herself engaged in one she both longed and worked hard for — a life of dry land, good friends, consistency, education and freedom.

So, basically, if you haven’t yet caught my drift, the trip was kind of a nightmare. For Suzanne, at least, it was. Sure, there were good times: riding on the bow with the wind in her hair, spotting whales and dolphins, meeting new people from time to time, the occasional short-lived stints with exotic pets like Kelly the parrot.

But this is also a tale of childhood lost, of ridiculously hard work — trimming sails, “rubbing down the hatches and gunwales with sandpaper, our hands becoming dry and coarse themselves,” of cooking, cleaning and preparing meals in a frequently storm-tossed mini kitchen, of on-and-off education requiring the haphazard receiving and sending of schoolwork at various island ports of call, and generally, of great physical and emotional struggle.

Writes Laurie Hertzel in a review in the Los Angeles Times (Oct. 19, 2023), “‘Wavewalker’ is not a shocking story of physical and psychological abuse, like Tara Westover’s ‘Educated’; nor is it brilliantly written, like Mary Karr’s ‘The Liar’s Club.’ It is a solid, compelling story about what it is like to be raised by parents who are almost certainly narcissists and who ignore their children’s most basic needs for education, love and approval.”

I mean, you’ve got to hand it to the parents for their courage and sense of adventure, but many times as I read this memoir, I found myself asking, “What is wrong with these people?”

The father comes off a bit like Captain Ahab of “Moby Dick” in his megalomaniacal dream of following Captain James Cook’s path around the world, and the mother’s personality and motives are truly odd and mysterious. She is often seasick or migrainous, and hidden away in a bunkroom, alternately demanding and negligent, mourning the loss of her beautiful wardrobe back on land. Yet, when the question arises, “Should we end the voyage or sail on?” she consistently votes for the latter.

I am glad for Suzanne Heywood for having the extraordinary discipline, focus, grit and drive to finally transport herself to a life more aligned with her own dreams, and glad for us readers that we can hold in our hands and read this honest, exciting, perplexing and (I keep using this word, but I mean it) compelling account of what it was like for this child, this teenager, this young woman to spend the eternity of her early years on a boat at sea. Highly recommend. (And, by the way, it would probably make a great Christmas gift for the readers on your list, as my sense is that few have heard about it.)

Onward we go, into the holidays. Batten down the hatches and anchors aweigh. Try and keep your sea legs as the season’s wake amps up, and may you find good books to keep you steady, intrigued and entertained, until we meet again. (Oh, and by the way, if you find a small box on your stoop one morning, you might want to think twice about opening it.)