An archeologist is like a historian with a trowel

If we historians wish to study a particular time period, there are often multiple sources we can consult. Not so the archeologist. Most often, the archeologist must use infinite patience to create that record through observation of details left behind by those being studied. An archeologist needs to have a genius of inference and the intuition of an artist.

A traditional series of test pits at a dig near Warren Falls in West Haven using trowels and shovels.

Sherlock Holmes said, “From a drop of water, a logician could infer the possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara without having seen or heard of one or the other. Thus, all life is a great chain, the nature of which is known whenever we are shown a single link of it.”

Yet even Holmes acknowledged it takes years of study, and it is an art.

A shard of pottery, discarded flecks of churt or flint, tools and other implements can provide dating evidence that establishes certain lifestyles and practices over time, and can give clues to infer a culture’s existence where no written records have survived.

Jess Robinson is our Vermont State Archeologist, and his presentation at the senior center on April 11, sponsored by the Charlotte Library and the Historical Society, was on one of the most difficult studies in local archeology and anthropology, pre-contact history of the First Nations to arrive around our lake. This study is difficult because the indigenous peoples of the Champlain Valley built with wood and hide, following the receding glacier northward when only oral histories existed.

The single clue of an ancient campsite may only be a darkened area in the earth that to the trained eye reveals intentional burning. What appears to us as merely a stone may be a prehistoric axe or grinding implement. I have been an enthusiastic follower of the BBC archeology series “Time Team,” which is on YouTube if you wish to check it out. One of their lead archeologists, Mick Aston, once said that archeology is a form of destruction of the site, so a dig must be done with patience and scrupulous attention to detail and documentation, in order to disturb as little as possible. Normally, their digs are sketched, photographed, GPS data points recorded and artifacts dated before being covered back over.

Robinson spoke of known or suspected indigenous sites that are surmised, but not excavated, primarily for their own protection. Due to limitations of money and staff, most often the state archeologist is called in to dig only when an area is threatened by development. Test pits are dug with extreme care to observe evidence at its proper strata, which can aid in dating it. United States archeology seems to favor test pits over the Time Team’s extensive use of trenches.

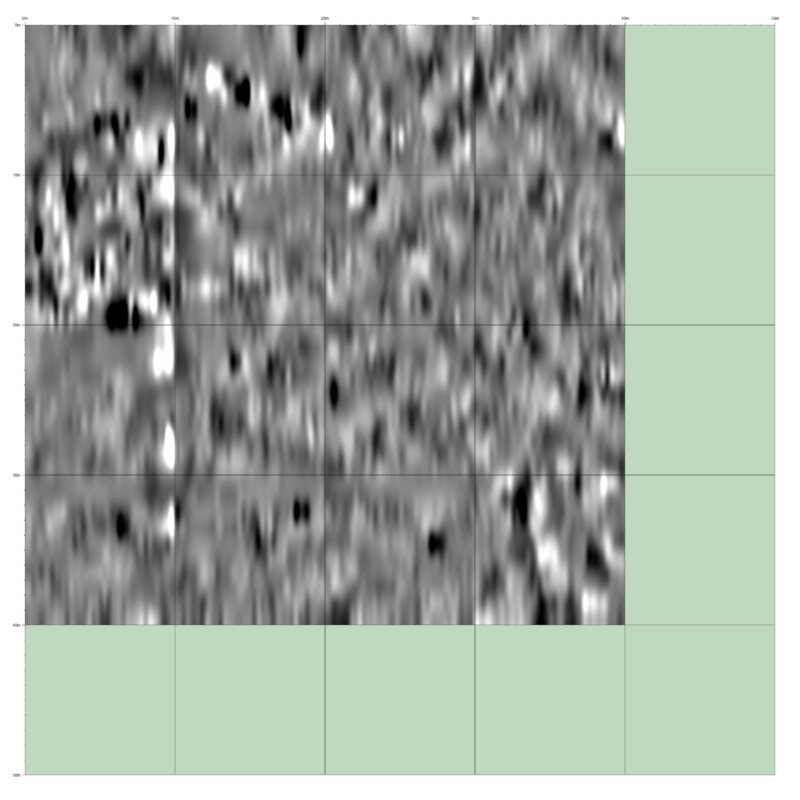

A magnetic gradiometry image from the east side of the Bradley Cemetery (East Burying Ground) on the west side of Spear Street about a half mile north of Hinesburg Road. Areas of high magnetic resistance are lighter in color; the white areas are stone. Areas of lowest resistance are dark or black in color, suggesting the ground has been dug. Graves appear black and are cigar shaped.

However, technology, called geophysics, can be employed to assist. These tools can include magnetic gradiometry, ground penetrating radar, MRIs for preserved bodies, and even laser scanning, known as LiDAR (light detection and ranging). Anomalies are located by the geophysics, which are then interpreted by a technician to suggest what is unseen beneath the soil surface, such as burn pits, burials, mud ovens, post holes or boundary ditches. Metal detectors are sometimes used to sweep the spoils pile, seeking small metallic objects that might have been overlooked.

The Charlotte Cemetery Commission has used geophysics twice. The University of Vermont archeology department completed a magnetic gradiometry survey of the Bradley Cemetery (East Burying Ground), which is on the west side of Spear Street a little more than a half mile north of Hinesburg Road and the Barber Cemetery (West Burying Ground) that is on Greenbush Road, south of Ferry Road.

Check the accompanying photo of the Bradley Cemetery; can you identify the graves? And then there are the underwater archeologists …

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Bill Regan, Chair, Board of Directors