Humble Superstar

Janssen-Heininger and group from Charlotte taking giant steps in treatment of cancer

Superstar — the word comes up again and again when you talk to people about Yvonne Janssen-Heininger of Charlotte.

Janssen-Heininger is a researcher at the University of Vermont and an internationally recognized expert in biochemical medicine because of her quest for ways to prevent or treat cancerous tumors caused by environmental factors.

Superstar — sound a little grandiose for a scientist whose research will most likely take years to come to fruition and with no ironclad guarantees that her endeavors will actually pan out? Well then, consider: Janssen-Heininger has recently nailed down grants from the American Lung Association and the National Cancer Institute totaling almost $6 million. She was also named UVM’s most recent University Distinguished Professor.

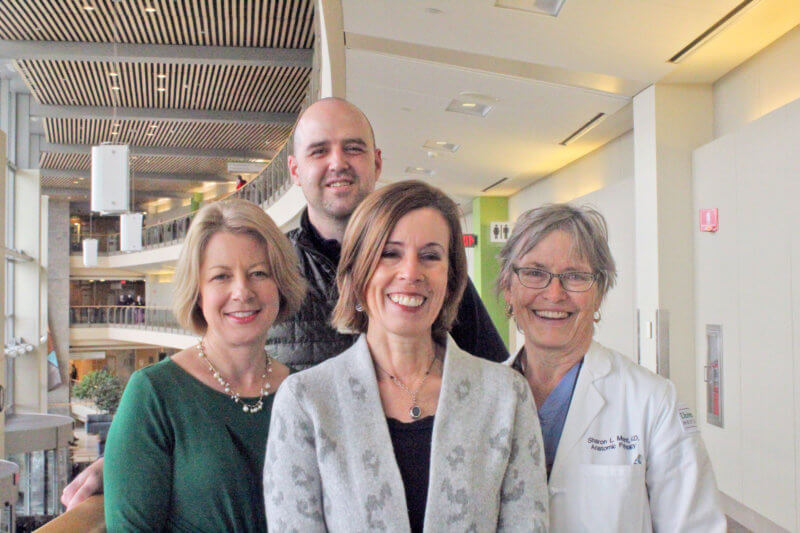

From left, Kelly Butnor, David ‘Bebo’ Seward, Yvonne Janssen-Heininger and Sharon Mount at the University of Vermont Medical Center. Many think these researchers, medical workers and Charlotters may be on the verge of changing for the better how lung cancer is treated across the world.

“She is an advocate for women scientists, having organized gender equity sessions at national meetings. She is also an outstanding mentor. She initiated our annual Research Day and other efforts to support our investigators,” Debra Leonard, chair of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, the department where Janssen-Heininger works, told Vermont Medicine Magazine.

Before Leonard finishes, that word pops up: “She’s a superstar, and I am so proud she is a member of our department.”

Try to get Janssen-Heininger to talk about her accolades and nary a trace of the word nor any hint of the superstar swagger comes up. She invariably steers the conversation to her colleagues. Janssen-Heininger loves the cooperative research atmosphere at the University of Vermont. And Charlotte.

“Charlotte should be extremely proud of the people who are contributing and collectively doing this research,” Janssen-Heininger said. “UVM is also very collegial. We work together to get things done.”

Among colleagues she mentions who have collaborated on her cancer research are four Charlotters — Brooke Mossman, David “Bebo” Seward, Kelly Butnor and Sharon Mount.

She is also very proud of the university, mentioning researchers she works with who have come from Duke, Michigan and other top research universities around the United States.

For a smaller university, UVM is playing in the big leagues when it comes to medical research. Janssen-Heininger has had many job offers elsewhere, but she doesn’t want to lose the experience of working with the “very interesting crowd of scientists” she collaborates with. Nor give up the rural beauty of Vermont.

“I’m not a city person. I need to have that quiet,” she said. “I need to have those moments at Whiskey Bay.”

Charlotte at the forefront

There’s a real possibility that major advancements may be made in how cancer is treated across the world — and this group of Charlotters could be crucial to those medical developments.

Discovering effective ways to treat lung cancer caused by environmental factors like smoking, coal mining or asbestos has a very personal connection for Janssen-Heininger. Originally, from Holland, both her grandfathers worked in coal mining there and died from work-related lung disease. She was already involved in research about environmental causes of cancer when, about 15 years ago, her father died from cancer probably caused by exposure to asbestos from his work on the docks.

She came to Vermont for the opportunity to work in the lab with Mossman. It was supposed to be a temporary experience. That was more 30 years ago.

The notion that Charlotte could prove to be at the nexus of major breakthroughs in cancer research is not at all farfetched, she said. For example, much of the research she’s involved in is directly inspired by research that Mossman did on mesothelioma.

“She is the world’s expert on mesothelioma,” Janssen-Heininger said, adding Mossman’s research made possible her own advancements and projects in the area of biochemistry. Mossman has not only been her mentor; she has been her inspiration.

Scarring connected to tumors

Mesothelioma is cancer that develops in the mesothelium, a thin layer of tissue that covers the lungs and other organs. The vast majority of instances of mesothelioma are caused by asbestos exposure, according to the National Cancer Institute.

Mossman worked in cancer research at UVM for over 30 years when a woman in that field was a rarity. In addition to her discoveries in cancer research, she paved the way and encouraged other women to go into an area of science many had felt intimidated by. Mossman was also named a UVM Distinguised Professor and is now retired as professor emeritus at the university.

It is a tribute to her legacy that four of the five Charlotte researchers are women. Janssen-Heininger continues that tradition by initiating gender-equity initiatives in the field.

The researchers at UVM, a good number from Charlotte, are using brand new technologies that give them a better look at how a tumor responds to interventions such as chemotherapy or drugs, Janssen-Heininger said.

She started her research years ago in chronic scarring, or fibrosis, in organs that was caused by environmental factors, most notably in the lung. Much of her research has been focused on fibrosis because once you develop a scar the chance of developing a tumor is much greater.

Other Charlotte medical stars

Another Charlotter in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine who helps with the analysis of tumor tissues is Seward.

In early November, Seward was also awarded almost $500,000 from the National Cancer Institute’s for his research into immunotherapy and lung cancer. He shares Janssen-Heininger’s enthusism for their Charlotte-centric group of colleagues.

“There are more unanswered questions than there are people and time, but we’ve got a really strong group,” Seward said. “We’ve been making progress on multiple fronts. We have a pretty diverse set of educational backgrounds, and we come at the problem from different sides.”

Seward is one of those who uses the term “superstar” in talking about Janssen-Heininger and shares her optimism about what UVM researchers from Charlotte might accomplish in the fight against cancer.

With an expertise in molecular and genetic pathology, for 75 percent of his time, Seward works on interpreting the mutational profiles of cancer tumors and talking with oncologists about what therapies might be best. For the other 25 percent of his time, he is doing research and writing grants.

Butnor is “a fantastic lung pathologist” who helps the team analyze tumor tissues, Janssen-Heininger said.

“I examine tissues from that are taken from patients either from biopsies or from surgery for pathologic diseases of the lung and diagnose them,” said Butnor. “I’m a physician who advises the physicians who are directly caring for the patient on what I see under the microscope, what the next step should be for the patient.”

As the medical director of the autopsy service at UVM, Mount has been a big help in getting tumor tissues for Janssen-Heininger and her team to analyze.

Mount confirms the other Charlotters’ diagnosis of Janssen-Heininger’s superstar status. When Mount was working on her master’s of public health, she went overseas to take a course she needed in public health at the University of Maastricht where she was amazed to see pictures of Janssen-Heininger.

“She’s famous in the Netherlands,” said Mount.

Janssen-Heininger’s excitement about her research is tempered by at least two sources of frustration. One is how long it takes to get from science and discovery to actually helping patients.

“Some of these drugs take 20 years to develop. And then some of them get shelved, and maybe they get shelved too soon,” she said. “I really would like to poke through some of this.”

Another source of concern is how much the research costs. Although getting almost $6 million in funds is wonderful, Janssen-Heininger said, it’s not enough. Not when a single experiment can cost $50,000.

“It takes a lot of funding and a lot of time to get these initiatives started. It takes a lot — and it takes a big team,” Janssen-Heininger said. Her current research project with the Lung Cancer Center at UVM has been in the works for over 10 years.

“We have a new, very outstanding director at the UVM Cancer Center,” she said of Randall Holcombe, who has recently come on board as director.

She’s optimistic that under his leadership the center may find ways to speed up the cancer research process. Holcombe is really interested in taking biochemical research results into phase one clinical trials to help more people sooner. And not just those with lung cancer, but other kinds of cancer, as well.

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair