Nonfiction thriller — you can’t make this stuff up

Ho, ho, ho. Here we go … on a toboggan ride, sliding rapidly towards Christmas, picking up speed the closer we get. That’s always the way it feels to me around this time of year.

People who know me well know that I don’t love it, this holiday … any more, really, come to think of it, than those toboggan rides of my youth — my wild cousins hooting and hollering in their woolen mittens and hats, all of us hanging on to each other for dear life in a desperate attempt to remain on the slippery, hard, ice-cold slab of hardwood zipping down the hill, snow whipping up in angry plumes into our red and quickly numbing faces.

But on to books … the very thought of which, I am noting, is calming my galloping heart (galloping at the thought of toboggans and the fast-approaching holiday).

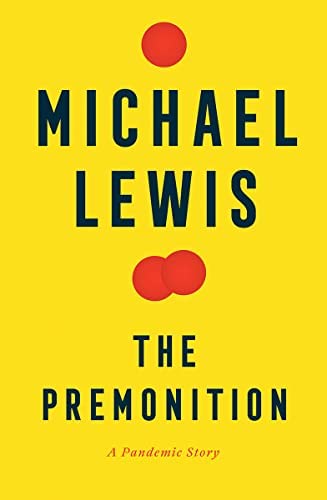

A book that I am wrapping up and giving away this season to the avid readers in my life is Michael Lewis’ The Premonition, A Pandemic Story. Though it’s nonfiction, it reads like fiction — hashtag: youcantmakethisstuffup.

A book that I am wrapping up and giving away this season to the avid readers in my life is Michael Lewis’ The Premonition, A Pandemic Story. Though it’s nonfiction, it reads like fiction — hashtag: youcantmakethisstuffup.

Lewis writes in an introduction that his job is “mainly to find the story in the material.” And that he has done, I would say, artfully, masterfully. The story he tells is mind-blowing, ever the more so because it is the truth.

Back in October 2019, nearly three years into the Trump administration and before anyone had heard of such a thing as COVID-19, a group of smart people called the Nuclear Threat Initiative collaborated with Johns Hopkins and The Economist Intelligence Unit “to create what amounted to a preseason college football ranking for 196 countries.” The Global Health Security Index, as the initiative was called, was “a massive undertaking involving millions of dollars and hundreds of researchers.” After many polls, statistics, models and consultations with experts in the field, countries were ranked for their pandemic preparedness. The United States came in first.

“The United States,” says Lewis, “was the Longhorns of pandemic preparedness. It was rich. It had special access to talent. It enjoyed special relationships with the experts whose votes determined the rankings.”

So, what the hell happened?

Read this book and you will have a much clearer idea … and see once again, or maybe for the first time, that truth is often stranger and more eye-popping than fiction.

Lewis (author of The Undoing Project, Liar’s Poker, Flash Boys, Moneyball, The Blind Side, The Big Short, etcetera) is definitely a writing pro, making the reader loathe to take a break from this rich and gripping story “about the curious talents of a society, and how those talents are wasted if not led. It’s also about how gaps open between a society’s reputation and its performance.”

“After a catastrophic season,” he writes, continuing the football theme, “management always huddles up to figure out what needs to be changed. If this story speaks to that management in any way, I hope it is to say: there are actually some things to be proud of. Our players aren’t our problem. But we are what our record says we are.”

The players in this book are admirable, unusual, unexpected, often eccentric and, more often than not, marginal, off the grid. They are the true and largely unsung heroes of the pandemic. The visionaries. The prophets. One gets the strong sense, as one reads on, that had leadership listened to these players, we wouldn’t be down a million Americans, and counting.

One of the first heroes we learn about is Laura Glass, a 13-year-old eighth grader at Jefferson Middle School in Albuquerque, New Mexico (talk about unexpected), the daughter of Bob Glass, a scientist at Sandia National Laboratories, created in the mid-forties to research nuclear weapons. One day, looking over her dad’s shoulder at his computer screen, she is struck by the thought, “It’s almost like the red dots are infecting the green dots.” Which gives her an idea for a project for the upcoming school science fair. A model to study how disease spreads.

Laura’s project inspires her father, who at some point in the process finds himself thinking, “Hmmm, if one could understand the way disease moves through a community, one might find ways to slow, maybe even stop, it.” He commences to read everything he can get his hands on about disease and the history of epidemics, including a book by historian John Barry about the 1918 flu pandemic, and soon comes to the realization that his daughter’s science fair project is dealing with a very important and real-life problem. The 1918 flu epidemic that killed 50 million people derived from a small number of mutations in a bird virus. This, along with his research and his daughter’s model, leads him to think about disease abatement in modern times.

The rest is history. A rich, multivalent, deeply unsettling history of real science, sincere, well-intentioned scientists and dedicated public servants pitched too often against a government whose job is supposedly to protect us. At one point Lewis writes, “The root of the CDC’s behavior was simple: fear. They didn’t want to take any action for which they might later be blamed.”

Another good sound bite: “Experience is making the same mistake over and over again, only with greater confidence.”

In this season of sledding, I recommend you jump on this toboggan ride of a nonfiction thriller and invite your friends to do so, also. I guarantee an exciting ride, and that you will never ever again see science, public health and our country’s government the same way. Excellent read. Highly recommend.

Oh, and happy holidays. Grit your teeth and hold on; it will be over soon.

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair