Managing for bats — an important member of the forest community

Scientists from the University of Illinois recently studied the effects of removing bats from a forest, finding that a forest without bats had three times as many insects and five times as much defoliation as a forest with bats.

The researchers postulated that this increased defoliation would increase forest vulnerability — making trees more susceptible to other stressors at a time when forests are already stressed from climate change, invasive species, deforestation, forest fragmentation and more. This research made me consider the many pieces and parts that make forests work, and, more specifically, the role that bats play in forests.

There are over 1,400 species of bats, accounting for about 20 percent of the mammalian species on Earth. Besides being diverse, bats are extremely numerous: about 25 percent of all the mammals on Earth are bats.

Vermont’s bat species can live 20-30 years or more (the little brown bat has been documented living as long as 34 years).

Contrary to the story told in cartoons, bats also live in trees. Managing your forest for bats is important for the health and habitat of these valuable members of the ecosystem.

Most species have only one pup (young) per year, making their populations especially vulnerable to decline. The United States is home to 50 species of bats, nine of which live in Vermont. Five of Vermont’s bat species are state and/or federally threatened or endangered.

All of Vermont’s bats are insectivores, eating about half their body weight — as many as 1,000 insects — per hour. Though there are many predators of insects, bats are the primary predator of nocturnal insects, including many moth and beetle species. In forests, insect defoliation is normal and natural, but insects exist in a dynamic balance with ecosystems and with their predators. Too many insects and too much defoliation — such as could be caused by the loss of bats — can create a major imbalance in our forests, with ecosystem-wide implications.

Bat populations in Vermont have been declining for a variety of reasons, but most dramatically from “white-nose syndrome,” a disease caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans. White-nose syndrome, first discovered in Albany, N.Y., in 2007, has killed millions of bats, including 90-100 percent of the bats on some sites.

Of Vermont’s nine bat species, six (five of which are threatened or endangered) congregate in large numbers in hibernacula — caves and abandoned mines — for the winter, while the other three migrate to southern climes. All nine species spend much of the summer in our forests, foraging, mating and raising their young.

Besides protecting hibernacula and water sources, managing forests for bats largely consists of encouraging two types of habitat: roosting habitat (where bats sleep during the day and raise their young) and foraging habitat.

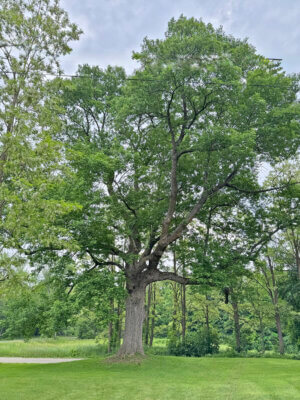

In the forest, bats roost under shaggy tree bark, in crevices and cavities (holes) in trees, in the foliage of large trees and on sunny cliffs and talus slopes. Active roost trees can be absolutely full of bats: some harbor hundreds of females with their flightless young.

You can improve roosting habitat by leaving or creating dead-standing trees (“snags”) in a variety of sizes and at different stages of decay. If snags aren’t naturally abundant in your forest you can create some by “girdling” a few unhealthy trees per acre. Additionally, retain legacy trees — large and old trees that are allowed to decline and die naturally — and all shagbark hickory, which are a particularly important roosting species for the federally endangered Indiana bat. If you are planning on cutting any potential roost trees, avoid doing so from April through October, when bats are active in the forest.

In general, great foraging habitat for bats consists of diverse, complex and multi-generational forests. You can encourage habitat like this by cutting small groups of unhealthy trees, which will both create canopy gaps (an important foraging feature for both bats and insectivorous birds) and encourage the development of new generations of trees. Between canopy gaps, you can improve bat habitat by thinning the forest: cutting unhealthy trees which are in competition with healthier trees. As you manage your forest, make sure to leave plenty of legacy trees, snags and cavity trees.

While it’s easy to forget about them, bats are an important piece of the complex community that is a forested ecosystem. Managing for bats is another way to help safeguard the health and the future of our forests.

(Ethan Tapper is the Chittenden County Forester for the Vermont Dept. of Forests, Parks and Recreation. See what he’s been up to, check out his YouTube channel, sign up for his eNews and read articles he’s written.)

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair