Cheng story warms hearts, wakes memories

A tale of tennis, tradesmanship and travel — Guy Cheng’s life’s story reveals deep, intertwined roots with Charlotters.

David Sisco talked about his stepfather at the Charlotte Library. His presentation on Sunday, Nov. 13, was also co-sponsored by the Charlotte Historical Society.

It highlighted his “pop’s” love for family, friends and Vermont with stories of Cheng’s journey from China to Charlotte. Some of the experiences Sisco related elicited nods of recognition or laughs in remembrance.

Cheng grew up in Tientsin, China, about 60 miles from Bejing. He was born in the spring of 1912, but the date is uncertain.

Cheng’s father, Lihing Cheng, was highly educated with a graduate degree from Yale. His experiences abroad led his son to follow a similar path. Cheng’s dream was to be educated in the U.S. and play professional tennis.

“To be a paid tennis player was frowned upon,” said Sisco.

That did not stop his dream. In 1933, Cheng’s father made arrangements with a general in the Chinese army to take care of the “misguided teenager.”

The general paid for him to go to Malaysia where he continued to play tennis.

Upon returning to China a couple of years later, his level had improved dramatically, and he was ranked No. 2. In 1935, while representing China in the Davis Cup he lost to the No. 1 player in the world, Don Budge.

Cheng played in over 20 matches in various competitions, such as the French Open and U.S. Open. In 1936, he played Budge and lost again in the U.S. Open.

Just before the tournament, he met a recruiter from Tulane University who offered him a full scholarship. Despite his experiences as a minority in an educational institution in the segregated south, in 1939 Cheng was the No. 1 doubles player in the Southeastern Conference.

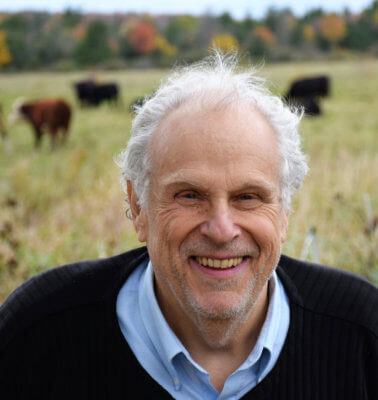

David Sisco shows a photo of Guy Cheng at his workbench. Sisco still uses the bench and some of his father’s tools today.

He traveled with his teammates and forged friendships, including with Cliff Sutter and his younger brother Ernie, who both won the NCAA singles championships in the 1930s while attending Tulane.

Cheng’s life took a more northerly turn, when the dean suggested he get a job for the summer. He found an ad in The New York Times looking for a tennis instructor at Camp Abnaki in Vermont. Sisco said his pop sent in his application and received an envelope with a bus ticket and directions about what to do when he arrived in Burlington.

“And the rest is history,” Sisco said.

One of the people Guy Cheng first met was Bob Adsit, Jr., a Charlotter who also worked at Camp Abnaki.

Sisco circulated a framed document — an act of Congress for Guy Cheng to be given permanent residence in the United States — dated May 25, 1948.

“This is where his love affair for Charlotte was cemented,” said Sisco. Charlotters, along with Sens. Ralph Flanders and George Aiken, spearheaded the petition.

Sisco said it passed unanimously.

“Within 15 days it went through Congress. Things back then could move,” joked Sisco.

Cheng’s life took a darker turn with him spending time in a sanitarium with tuberculosis and losing a lung. His friend Bob Adsit came to visit him and upon seeing the conditions, was able to move him to a better location.

During his recuperation, he began making jewelry. He returned to Charlotte, and he and Adsit looked at real estate, particularly an old schoolhouse on Route 7, closed due to the construction of Charlotte Central School.

He purchased the property for $2,000 and launched his jewelry business, Guy Cheng’s Gifts, and also had a place to live. The shop, off Route 7 in Shelburne, is known for its front door: a distinctive red-and-black color scheme and circular design.

Cheng did well, began playing tennis again and married his first wife, Jean. He also adopted her daughter Dawn. But the couple divorced a year later.

During his time as a jeweler, he was commissioned to make lots of wedding rings. One of his signature pieces was an “initial” ring, a distinct style of initials in a block-type font. He also made custom rings for area camps. His reputation increased when Tiffany and Company began buying Cheng’s swirled gold bracelets in the 1950s.

Martha Stone, the treasurer of the Charlotte Historical Society, and Roberta “Chick” Wood both stood up at Cisco’s talk to show examples of the jewelry Cheng had made. Stone worked in Cheng’s store and had a beautiful gold ring.

Wood showed a swirled gold bracelet and matching necklace Cheng had made for her mother.

Sisco talked about how Cheng and his mother, Barbara, first met on a blind date at a hockey game in 1968.

“They had an incredible 30-plus year relationship,” said Sisco. “It was so wonderful to see.”

“The impact Charlotte had on Guy was profound,” said Sisco, as he shifted from one family photo to another, including photos of his parents’ wedding day with Adsit as the best man; his mother’s 1973 graduation as a doctor of experimental psychology, a field with few women at the time; his sister at Charlotte Central School. In this photo the children are eating lunch while being watched over by Ethel Atkins.

“Everybody knows Ethel,” said Sisco, which got a laugh from many in the audience.

Sisco ended his talk by reading letters from his siblings, who “clarified” varying points from their perspectives.

“He had a very challenging start in life, but he loved people. All sorts of people were drawn to Guy,” said Jennifer Adsit, Bob’s daughter-in-law.

Guy Cheng passed in Dec. 9, 1998, after a long life in Vermont with many connections to the community.

“He was giving to the community, but the community gave to him,” said Sisco, “It gave him a wonderful business and a wonderful life.”

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Bill Regan, Chair, Board of Directors