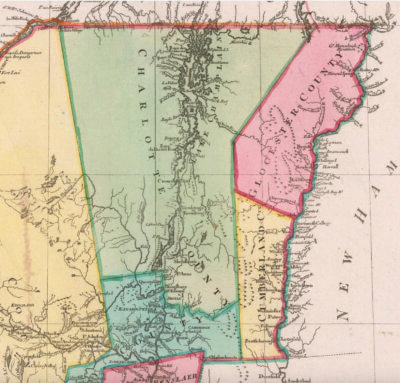

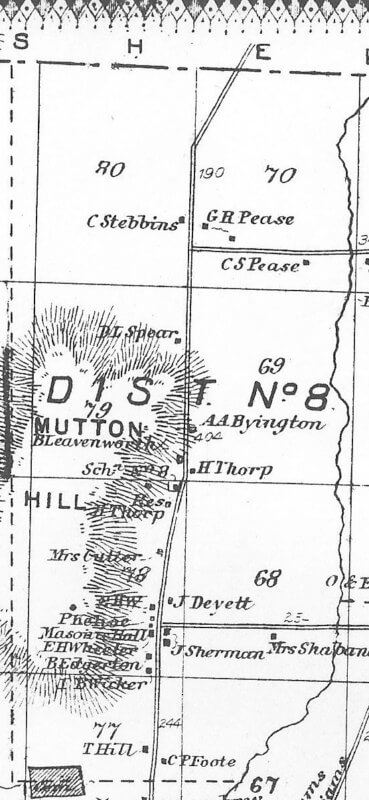

Charlotte School #8 was known as the Mutton Hill School

In this article we identify Charlotte School #8, aka the Mutton Hill School, located on the west side of Route 7 (Ethan Allen Highway), just north of the entrance to the Charlotte Park & Wildlife Refuge.

The house still stands, partially hidden by hedges and trees, and is incorporated into a home.

The district itself was oddly shaped —narrow and almost rectangular — generally serving families along a portion of the Route 7 corridor; bounded by the ridge to the west, and McCabe’s Brook to the east.

Eight-month-old Gerald Roberts sits on the southside of the Mutton Hill School in May 1950. Route 7 is to the right.

Of note is the home of Mrs. Sylvia (Martin) Cutter (in town grid 78). She was born Sept. 29, 1788, and is credited with being the first female born in the town of Charlotte.

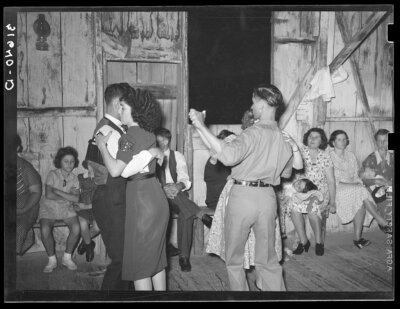

Videos produced in Vermont in past years, from “Vermont Memories I-III” in the 1990s through the 2015 “Life in Series” covering each Vermont county’s history in the early 20th Century, preserve nostalgic memories people felt for their one-room schoolhouse experiences.

Schools have evolved over the last 100 years; but whether beneficial is an issue being debated. Why do many believe that important elements of education were sacrificed in the press to consolidate the district schools, and subsequently town schools into larger districts?

“The difference between yesterday’s schoolhouse and that of today might seem to be merely the difference between two kinds of architecture and the difference of size. The real difference, however, is the simple difference between yesterday and today, and the way we live it. Education, like modern everyday life, has suddenly become regarded as a means of making more money. Startling as it sounds, life’s values have become all too linked with the dollar, and the diploma is openly regarded as a guaranteed bank account,” Eric Sloane writes in The Little Red Schoolhouse. “It seems worthwhile reviving any kind of spirit at all in this modern world so starved for lore and lacking in individual spirit: classrooms now have become more like business offices than halls of learning.”

Unfortunately, this seems valid when college and education administrators promote the notion that only a person with a degree can get a respectable good-paying job. That the education institution is ill informed is outlined in multiple articles decrying graduates’ difficulty in finding the expected employment, while meantime drowning in debt. It would be unnecessary to forgive student loan debt if the promised financial rewards were tangible. Colleges, many hoarding billion-dollar endowments, seem disinclined to support students financially; and the government response is to hand out more loans and grants like alms. Effectively this makes today’s scholars the conduit enabling colleges to feed from the federal trough.

While many disciplines do require advanced education, Robert Fulghum suggests it is not always necessary for success, and concludes in All I Really Need to Know, I Learned in Kindergarten, “Too much high-content information, and I get the existential willies. I keep sputtering out at intersections where life choices must be made and I either know too much or not enough. … Wisdom was not at the top of the graduate-school mountain, but there in the sandpile …”

Individuals often get caught up in “the grass is always greener” syndrome, Henry Miller argued in 1936, almost 100 years ago: “The dilemma in which we find ourselves today is that no matter how much we increase the purchasing power of the wage-earner he never has enough. … Men imagine that they need money, that if they had it they could satisfy their desires, cure their ills, insure their old age, and so on. Nothing could be farther from the truth. … The worker thinks he would be better off if he were running the factory; the owner of the factory thinks he would be better off if he were a financier; and the financier knows he would be better off if he were to clean out of the bloody mess and living the simple life.”

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair