Speeding: What have other towns done?

There’s no proof that drivers in Charlotte have recently fallen into a habit of traveling at higher speeds than they used to.

In 2013 and 2017, the Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission placed automated traffic recorders in Charlotte, first on Hinesburg Road and Spear Street, and then on Ferry Road and Greenbush Road. Publicly available data collected at the same spots in 2021 showed little to no change in speeds.

Speeding often plays a role in car accidents, and according to figures from the Vermont Agency of Transportation (or VTrans), Charlotte has averaged 41.3 crashes annually over the last decade, with a high of 57 in 2016. Forty-one crashes occurred within town limits last year and 44 the year before that. In 2022, Charlotte is on pace for a better year than usual, with only 15 crashes recorded as of Oct. 18.

Recent meetings of the Charlotte Selectboard, however, suggest that unsafe driving has never been a more pressing concern locally. On Sept. 26, speeding-related complaints by residents stretched the five-minute “public comment” portion to a half an hour.

Signs, including in the median, and painted crosswalks are strategies Shelburne has used to try to reduce speeding.

Neighboring towns tell similar stories. Throughout Chittenden County, municipal officials, prodded by concerned citizens, have sought in different ways to address the dangers posed by aggressive motorists. Sometimes, it can be hard for them to tell how much progress they’ve made.

“I’ve been in public service for quite a long time,” said Shelburne Town Manager Lee Krohn. “In my experience — and I don’t make light of it — people complain about speeding everywhere. Everywhere. Sometimes it’s real; sometimes it’s perception.”

“I think it feels worse now because traffic was a lot quieter during the height of COVID,” he conjectured. “The question always is: ‘Well, what do you do about it?’”

Krohn pointed out that Shelburne has erected “several” speed feedback signs, whose dynamic digital displays let drivers know how fast they’re going in the hope that they’ll want to slow down.

“I’ve seen those popping up more and more frequently in towns throughout Vermont, especially along entries into the hearts of villages or downtowns,” he observed. “I think they’re a good idea in certain locations, but you don’t want to overuse any particular device.”

Studies by safety experts have established to varying degrees that feedback signs can be effective, but observers have their own impressions.

“We have one on Mechanicsville Road in the village,” said Hinesburg Town Manager Todd Odit. “I run frequently, and it’s in a speed zone that is 35. And I’ll routinely observe people going 42, 45 by that speed sign.”

Some feedback signs can transmit data that might indicate empirically whether frequent speeding has persisted after their installation, but most don’t contain a memory bank.

“It probably requires a more costly electronic system,” Krohn speculated. “Just the regular signs themselves are several thousand dollars.”

Shelburne also owns a mobile radar cart, however, and when it’s set up to record speeds, town officials can harvest the numbers later for examination, without commissioning a traffic count by the Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission.

“We collected a wide array of data some years back,” Krohn remembered. “It showed that, for the most part, the vast majority of motorists were traveling within a reasonable plus or minus range of the posted limit.”

Charlotte doesn’t have any permanent speed feedback signs, but it did purchase a mobile radar cart in 2014. Lieutenant Allen Fortin, who works in the Chittenden County Sheriff’s Office as a highway safety coordinator (a position funded by the Vermont State Highway Safety Office), rated the latter’s ability to slow drivers more highly.

Huntington can pull data from its speed signs. The first year after speed humps were installed, it seemed to show the speed hump reduced speeds, but town officials haven’t pulled the data since.

“I’ve never been a big fan of the permanent ones. People get used to them,” Fortin said. “I would get the ones that you could move around, so you could put it on this road for this month, and then, next month, you move it to a different road.”

At the moment, however, Charlotte’s mobile radar cart covers limited ground. Town administrator Dean Bloch cited technical difficulties.

“At the time we bought it, our town planner was able to program it,” he said. “It does take some special knowledge.”

That planner changed jobs two and a half years ago. The town has deployed the cart as recently as this summer, but using it at a fresh location would require changing its setting.

“It operates on roads where the speed limit is 50, but we’re trying to get it to operate on roads with lower speed limits,” Bloch said. “It needs to be reprogrammed because there’s some speed at which it begins to turn red or get angry at you or something.”

In Shelburne, feedback signs aren’t the only electronic devices flashing at drivers. In and around the downtown, upgraded crosswalks come with signage featuring what planners call RRFBs: button-activated Rectangular Rapid Flashing Beacons. A local Boy Scout prompted the installation of the ones outside the town office in 2019.

“When you’re working toward your Eagle rank, you have to do some kind of community project. And this particular Eagle Scout chose to pursue a grant to help the town get these,” Krohn said. “So, he got a grant; we paid the rest and had the state contractor install them because they’re right on a state highway, and they need to be of a certain design and strength.”

Shelburne has contemplated other traffic-calming measures to makes its village center less hospitable to fast-moving cars.

“Downtown Burlington has sort of gone to a certain extreme,” Krohn said, “where they’ve put gigantic planters at intersections and built these things called ‘bulb-outs,’ where you actually extend the sidewalk and curbing out into the street to narrow the length that a pedestrian has to cross and make it harder for cars to travel through those tight intersections.”

“Anything is theoretically possible,” he continued, “but when you put obstructions into a heavily traveled roadway, it can create its own risks of accidents or snowplows running into these things. So, it’s a real intriguing, dynamic process of trying to find a balance between the needs of multiple users of roads and what makes sense in the right place.”

In Vergennes, City Manager Ron Redmond addressed the question of what the municipality has done to reduce speeding by pointing to the Vergennes Police Department.

“From the day I came came into Vergennes, one of the first complaints I had was the speeding and motor vehicle complaints,” Police Chief George Merkel said. “So, I made that a priority.”

“We identified the areas that were the problem areas, the most likely to get complaints. We did an analysis of the calls to see what days of the week, what times of the day, and then we developed a data-driven process,” he said. “We devoted our time in those locations and during those periods, and we started making some headway.”

“We developed a reputation that you didn’t speed through Vergennes because you were going to get stopped,” Merkel summarized.

The Vergennes Police Department has seven officers, who work 10-hour shifts. By Merkel’s estimate, an average officer on an average day spends four to six hours on traffic enforcement.

Merkel also cited public awareness and education as “a big part” of the Vergennes Police Department’s efforts to improve safety on the roads.

“We go to the local schools. I’ve gone to the Rotary Club. I’ve put articles in the paper. In the spring we talk about bicycle safety and helmets and crosswalks and being vigilant for bicycle riders,” he said. “Officer Stacey teaches classes to motor vehicle offenders.”

Over the course of more than 13 years, Merkel gradually saw fewer complaints of speeding, he said, as well as fewer incidents of drunk driving.

Merkel retired on Oct. 31, citing a climate of “continued and unwarranted disrespect” in a letter to city officials. In 2020, accusations of racially biased patrolling and overspending on law enforcement in Vergennes stirred a citywide debate that led to the resignations of the mayor and three aldermen.

Charlotte, which has no police department of its own, contracts the Vermont State Police for eight hours a week of traffic enforcement. In 2021, the Vermont Judiciary recorded 13 municipal fines for traffic violations in Charlotte. As of the most recently published report in August, this year has seen just six.

“When the selectboard first decided to have enforcement done — and I’m talking about recent times, within the past 15 or 20 years — they hired the Chittenden County Sheriff,” Bloch said. “Considering they’re pulling over town residents, the style of the sheriff was a little bit heavy-handed. And not to say that the selectboard wasn’t interested in having tickets issued, but the manner of the interactions was not very professional at that.”

The Shelburne Police Department subsequently took over the town’s contract, which “worked very well for many years,” until it got too expensive. Vermont State Police followed.

Within Charlotte, far fewer traffic stops occur on town roads than on Route 7, where the state collects penalties on its own behalf. In total, Vermont State Police pulled over 111 drivers in Charlotte last year, compared to 335 in 2020 and 871 in 2019. Across the state, Vermont State Police traffic stops have declined precipitously from a recent high of 64,093 in 2017 to 10,332 in 2021.

Jonathon Weber, who manages the Complete Streets Program at the Burlington-based advocacy nonprofit Local Motion, argued that traffic enforcement requires “a lot of resources to do at scale” and offers “very limited effectiveness” even so. He contended that “changes in land use and in the design of the road are the only ways to sustainably address speeding.”

“Drivers adjust their speed and their behavior based on cues they are given by the roadway. Those cues include things like the width of the roadway and how much of a clear zone there is around the roadway. If there are trees or houses or buildings very close to the road, people will tend to slow down and be more aware. Even bends in the road can cause people to drive more slowly,” he said.

“Also, the presence of people walking and biking and activity slows down drivers. That sort of starts to get into the land-use topic,” Weber said. “You’re not going to have people around in a rural area, generally, if there are no destinations. And if the destinations are so far from the origin that it’s not realistic to walk or bike, the people at those destinations are all going to drive to get there. So that doesn’t really help you fix your problem.”

On Oct. 24, the Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission presented an East Charlotte Traffic Calming Study before the selectboard, recommending curbs, medians and even public art to “create a sense of place” that would have the effect of lowering vehicle speeds. With additions of this kind, either of Charlotte’s villages, in theory, could start a journey toward becoming a dense, walkable, bikeable community of the sort that Local Motion promotes statewide, but ultimately, it would take more than traffic-calming measures.

“That requires buildings, and you know, Charlotte doesn’t have a lot of them,” Bloch said.

Local Motion organized a survey of walking and biking habits in Charlotte last year. The organization has found local allies, including on the Charlotte Energy Committee, which has begun to envision a small park-and-ride at the new town garage that would facilitate a Green Mountain Transit bus stop, thereby reducing individual commuter trips on Route 7 by speeders and non-speeders alike.

Townspeople have debated various plans and ideas of this nature for years. In 2012, at Town Meeting Day, voters authorized an expenditure up to $77,000 to construct a sidewalk on Ferry Road in West Charlotte. A few weeks later, residents submitted a petition with enough signatures to force a second vote, and this time, the sidewalk lost.

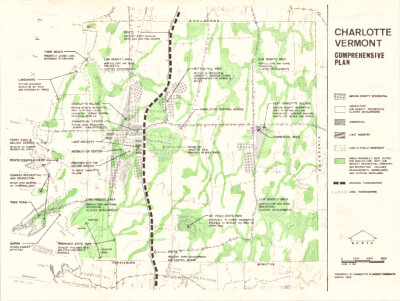

Last year, the Charlotte Planning Commission began a process to update the town’s land-use regulations, and voters will now consider an initial set of amendments on their November ballot. But in the absence of a wholesale transformation of either village, smaller roadway adjustments are possible, according to Weber.

“One example is just simply not having a center line, that yellow center line, on the roadway. That has been shown to reduce speeds, sometimes by as much as 7 mph,” he said. “It requires drivers to think a little bit more about their position on the road, and that encourages slower speeds.”

Towns can implement this change in downtowns or in rural areas, Weber noted.

In the latter, there may be few pedestrians around, but speeders still pose a danger to other motorists and, often, to recreational cyclists, who make frequent use of Charlotte’s back roads. Off-road networks of multi-use paths, like the one under development by the Charlotte Trails Committee, can provide alternatives, but few offer enough mileage to satisfy dedicated riders.

Kevin Bessett, a Richmond resident who serves as president of the Green Mountain Bicycle Club, pointed to the perils of Mt. Philo Road at rush hour, with “very evident” speeding and no shoulder for refuge. He highlighted the helpfulness, elsewhere, of fog lines, the painted white stripes that narrow the roadway and orient drivers by demarcating its right-hand boundary, even in the absence of a proper shoulder.

“Another benefit, too, is that these lines provide a point of reference for the cyclist,” Bessett said. “For example, I use the white line as a marker to ride on or to ride to the right of when cars are behind me.”

According to Sai Sarepalli, a transportation planning engineer at the Chittenden Regional Planning Commission, Vermonters sometimes hope to control speeds on country roads simply by lowering the limit, but a wide, empty road will invite speed no matter what the signposts say. By his account, surveys have shown that drivers usually forget the posted limit “five to 10 seconds” after seeing it.

“The road dictates the speed, and just arbitrarily reducing the speed limit, in most cases that I’ve noticed, it does not reduce the operating speeds of motorists,” he said. “They’ll drive at a speed where they feel comfortable.”

The town of Huntington, with a population of 1,938, has few businesses and little pedestrian activity, but plenty of drivers pass through on their way to Camel’s Hump State Park. A few years ago, municipal officials sought to control speeds in the lower village by installing a speed hump — a gentler version of a speed bump — at its southbound entry, along with feedback signs and painted speed limits on the blacktop.

This year and last, Charlotte deployed seasonal speed bumps of its own near the town beach and at Thompson’s Point, but the Charlotte Volunteer Fire & Rescues Services has advocated against their more extensive use. Charlotte Volunteer Fire & Rescues Services cited data from Oregon and Illinois to warn of slowed emergency response times.

“The delay could be anywhere between three and 10 seconds. While that does not sound like much, consider that a fire doubles in size every minute it goes unchecked,” said Chief Justin Bliss, who also noted “a potential for increased maintenance costs” for fire trucks and a possible “increase in patient discomfort and potential risk to providers in the back of an ambulance.”

In Huntington, the speed hump on Main Road has been an apparent success. The town checked to be sure.

“I’m able to pull data off of the speed signs,” said Huntington town administrator Barbara Elliott.

She said they pulled the data the first year, but haven’t since. That first year, it seemed to show the speed hump reduced speeds.

But, even here, the simultaneous introduction of multiple traffic-calming measures would confound a data-based analysis of any single tool’s stand-alone efficacy.

“It’s so hard to get a controlled environment to say X impacted the speeds, because there are so many other variables,” said Chris Dubin, a transportation planner at the Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission.

According to Dubin, the towns that commission the Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission for traffic safety studies rarely call them back to examine the results of their subsequent actions. “I mean, we would probably love to, but oftentimes it’s just onto the next thing, unfortunately.”

But Dubin’s colleague, Sarepalli, emphasized that researchers at the Federal Highway Administration have already “proven” the location-contingent effectiveness of all the standard engineering tools for traffic calming. And few towns will spend money on measures that “are not cheap,” as he put it, without an engineer’s input on implementation.

“Engineering countermeasures, such as changing roadway width, setting appropriate speed limits or installation of speed bumps, are context-sensitive, so it’s generally a site-specific assessment to determine what is appropriate and feasible in a particular location,” said Ian Degutis, a traffic engineer at the Vermont Agency of Transportation.

The Vermont Agency of Transportation urges towns to adopt a diverse strategy of techniques to address speeding.

“The best speed management practices,” Degutis said, “are a combination of appropriate engineering, educational and enforcement techniques, as all of these components working together are more effective than any of them can be alone.”

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair