Saving the butternut — important part of saving forests

Butternut (Juglans cinerea) is an enigmatic tree. Also called white walnut, butternut is the hardiest member of the walnut genus, with a range stretching north into southern Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick, as far west as Minnesota, Iowa and Missouri, and south to Tennessee.

In Vermont, butternut trees are usually found on rich, moist soils, growing alongside sugar maple, basswood, white ash and plants like maidenhair fern and blue cohosh. It is shade-intolerant, needing lots of sunlight to thrive. While butternut was likely never a common or long-lived tree in Vermont’s forests, it is becoming increasingly uncommon and shorter-lived due to the prevalence of a non-native pathogen called butternut canker.

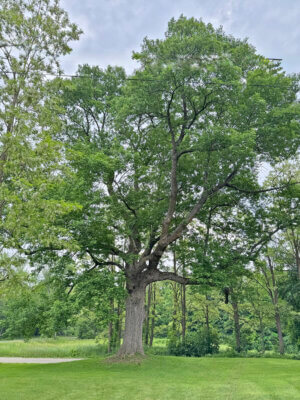

Butternut trees produce butternuts: a hard-shelled, fatty nut — much like a walnut — encased in a fleshy, green, football-shaped husk. Butternut has a compound leaf of 7 to 17 pointed leaflets, unfurling from brown twigs with distinctive large, light-brown terminal buds and leaf-scars that look like little “monkey-faces” with yellow “unibrows.” Their bark is patterned with narrow, interlacing ridges, similar to that of ash trees but darker in color. When stressed or afflicted with butternut canker (as they usually are), butternut bark is black and ashy-gray and its ridges look “sanded-off.”

Butternut is culturally important to the Abenaki, who call butternut bagon. Abenaki and other indigenous peoples eat butternuts and use their fleshy husks and the tree’s bark as a dye; the abundance of butternuts at archaeological sites suggests that indigenous peoples may have planted and dispersed the species for millennia. After European colonization, butternut trees were widely planted by colonists and butternuts became an ingredient in traditional New England cuisine.

While butternut trees were historically prized for their nuts (rather than their wood), today butternut lumber is used for a variety of purposes — most of them ornamental. Butternut wood is soft, light and pretty, an excellent carving wood. Butternut logs can be sold living or dead, and butternut lumber is often full of character, including the wormholes prominent in dead trees. Butternut is an awful firewood — as an old-timer once told me: “It burns as well as a snowball and produces half the heat.”

In today’s forests, healthy butternut trees are extremely rare due to a fungus called butternut canker (Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum). Butternut canker was first discovered in Wisconsin in 1967, perhaps introduced on Asian walnut trees. Dispersed by wind, rain and insects, this pathogen creates black cankers on butternut’s bark which proliferate until they girdle and kill the tree. According to the US Forest Service, close to 100 percent of butternuts in its native range are infected, with mortality rates exceeding 90 percent.

Efforts have been made to study and promote resistance to butternut canker using a variety of methods, including crossing butternuts with Japanese walnut (Juglans ailantifolia). Interestingly, a certain amount of hybridization between butternut and Japanese walnut has been occurring for over a century. Japanese walnuts, especially the cultivar known as Japanese heartnut, have been planted in North America since the 1800s. This species naturally hybridizes with butternut, creating a tree called “buartnut,” which was noted in the United States by the early 1900s. While buartnuts are more resistant to butternut canker than butternuts, hybridization comes at a risk: potentially eroding some of the unique and adaptive genetic qualities of the butternut species.

Each native tree species has a unique role to play in Vermont’s forests. Forests are natural communities: complex assemblages of species which are greater than the sum of their parts and enriched by diversity. The loss of a tree species impacts forests in profound ways, and butternut is just one of several important tree species that we have lost, that we are losing or whose role in our forests has been radically changed as a result of a non-native pest or pathogen — others include elm, beech, chestnut and ash.

In a changing world, taking care of forests means supporting their resilience and their ability to adapt. Doing our best to save butternut is just one piece in this puzzle — others include stopping deforestation and forest fragmentation, controlling non-native invasive plants and addressing the many other threats to forest health and to biodiversity. It’s up to us to help forests respond to the profound challenges of the modern world as they move into an uncertain future.

Ethan Tapper is the Chittenden County Forester for the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation. See what he’s been up to, check out his YouTube channel, sign up for his e-news and read articles he’s written.

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair