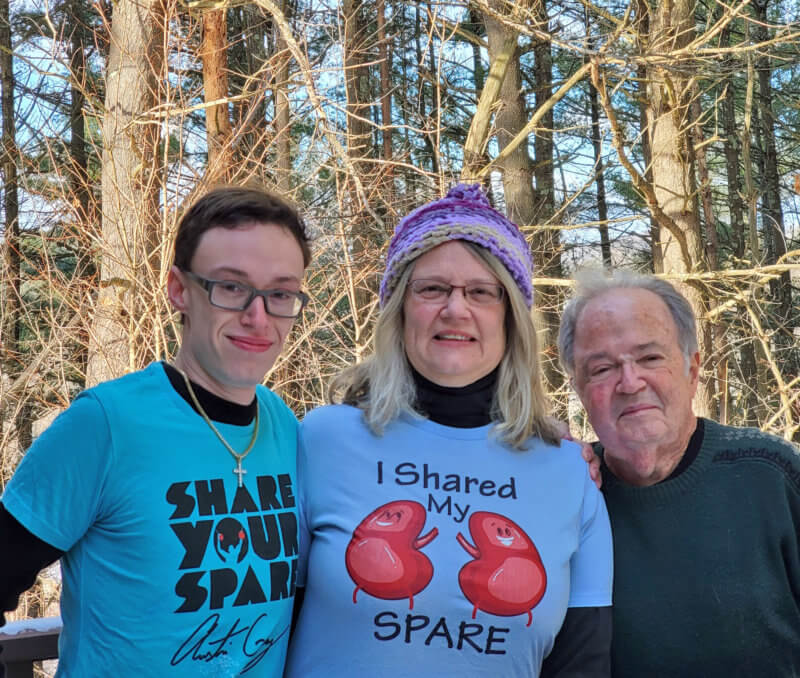

Jim Fox and Christa Duthie-Fox: A happy ending from paying it forward

It’s not a stretch to say that the National Kidney Registry may have saved Jim Fox’s life. His kidney was failing, none of his family members was a match, and the waiting list for a kidney was excruciatingly long. Through the registry, his wife, Christa, was able to donate a kidney to a total stranger, and, in return, another total stranger donated a kidney to Jim. Paying it forward worked, and four months later Jim is back home with a new lease on life. In fact, he may be the person responsible for you reading this newspaper, which he began delivering in 2021.

Jim was only 15 when his kidney failed in 1965, but his father was a match and donated one of his. “This was in the early days when it was still considered an experimental procedure,” Jim said. “It was part of a government-funded research project.” Unfortunately, 15 years after the transplant, the donated kidney began to fail. “The University of Vermont had a fledgling program for transplants,” Jim recalls. “They had one surgeon who did the procedure.” Jim received a cadaver transplant in 1980 that lasted for 40 years.

When his second donated kidney failed in May of 2020, Jim began the lengthy process of kidney dialysis, spending four hours at a time, three days a week, hooked up to a machine. Jim’s brothers and a cousin volunteered to donate a kidney but neither was a match. UVM now has a well-established transplant program, but the waiting list for a kidney then was a minimum of five years.

That’s when Jim and Christa turned to the National Kidney Registry. “A person donates a kidney which goes into a pool,” Jim said. “It doesn’t go directly to the recipient, but it triggers a chain of events that matches that person’s donor to someone else in the pool. It’s quite efficient and it shortens the waiting line significantly.” Jim’s first transplant had been at New York Presbyterian Hospital and he still had family in the New York City area. Since UVM is not part of the registry, he opted to return to New York for the procedure.

A teacher at Charlotte Central School at the time, Christa immediately volunteered to donate a kidney. She went through a battery of tests and was told she could donate at her convenience. “It was a full evaluation of my health,” Christa recalls. “It felt like a gift to find out I was a very healthy 59-year-old.

Christa decided to donate during the December 2020 holiday break. “It has to happen at a certain time,” she said, “so the kidney can be implanted the same day.” Christa’s operation was scheduled for Dec. 16. She was supposed to have a single room but there were so many Covid patients that the wing was almost full. “The next day there was a big storm and all surgeries were cancelled,” she said, “so we were lucky to get it done.” Her kidney was implanted in a 65-year-old New Jersey man, which jump-started the process of looking for a kidney for Jim.

“Because it was my third kidney I’m fairly well loaded with antibodies,” Jim said. “It was a less than ideal situation. I would only match 15 percent of the available kidneys, but they found a strong match and I was scheduled for the transplant in May 2021.” Fate intervened when Jim was bitten by a tick and contracted anaplasmosis. “That knocked me for a loop,” he said. “I was in the hospital for a week so they had to cancel surgery.” In August, a new donor was found and Jim had surgery on Sept. 21. He has since been in contact with the Minnesota-based donor who entered the program in the hope that a friend of hers would be able to get a transplant. One complication for Jim’s surgery was finding room for the new kidney without taking out an old one. The doctors removed his appendix to fit the kidney in place.

A former engineer in orthopedics at UVM, Jim believes he may be the longest living recipient of a kidney transplant. Having been through three operations, he recognizes how much the procedure has improved. He doesn’t remember much about his first transplant but does recall that he was in the hospital for three months. After the second surgery, he was in the hospital for 10 days, but this time he was only in for three days. Similarly, when his father donated a kidney, doctors made an incision in his side and had to remove a rib, leaving an eight-inch scar. Christa’s operation was done robotically and laparoscopically, leaving her with two small spots around her belly button.

“We are so grateful for all the steps along the way,” Christa said. “The fact that I was healthy enough to donate, the fact that I was able to donate the day I did, and the fact I was able to take medical leave from school.”

As part of the transplant program at New York Presbyterian, prospective recipients must visit the clinic several times a week for a period of months prior to surgery. Jim credits his cousin, who let him stay at her house an hour and a half outside the city, and his brothers, who took him in for his 7 a.m. appointments for making that process easier. Christa also stayed with the cousin, who took her to the hospital for her procedure. Jim was quick to praise his family for their roles in the process and even quicker to lavish praise on his wife. “This article should be about Christa,” he said. “She’s the real star. Her willingness to get involved at this level was immediate and without hesitation. I’m supremely grateful to her.”

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair