Burning snakes and stained-glass windows: a trifecta of memoirs

Hello, everyone. I hope you are having a great late summer, enjoying your days, and squeezing in some reading time. I have a stack of books I have read lately and an equally tall stack of books I am looking forward to reading in the future. A bounty of books. A tower of reading yet to come. Today the rain is pouring down, making it an ideal day to curl up with a book. But instead, I will sit upright and tell you about some books you might think about reading yourself. I believe the last article you got from me was about breezy summer reading. Well, I seem to have shifted gears, as you will see.

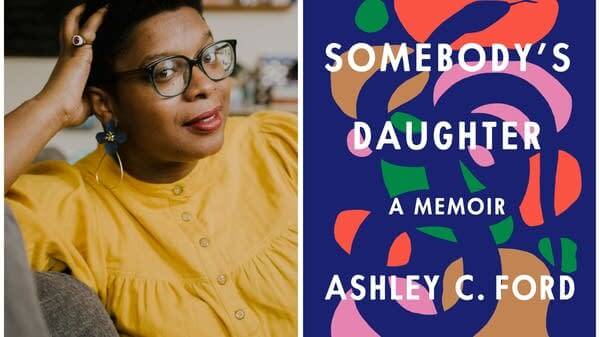

Somebody’s Daughter, a memoir by Ashley C. Ford, begins with a haunting frontispiece by Izumi Shikibu: “Although the wind blows terribly here, the moonlight also leaks between the roof planks of this ruined house”—followed closely by a letter to “Ashley” from “Dad,” in which we learn that the latter has been incarcerated for 20 years and has only recently received a letter from his daughter Ashley, who is no longer a little girl, but a woman. He tells her she will always be his favorite girl, that he is grateful to be her father and wants desperately to be forgiven for all the pain he has caused her, that he is going to create a beautiful life for himself and is planning to show Ashley and her brother how much he loves them, and that…he is coming home. This book is riveting, emotionally jarring, honest and affective. One memorable and telling scene takes place when Ashley and her grandmother (a refuge for Ashley in the storm of her young life) are standing together in the area beyond the grandmother’s backyard “where my great-grandfather let the grasses grow long.” Ashley’s grandmother takes a shovel and digs a hole in the soft ground. In the hole are a bunch of garden snakes “in some sort of a knot, though not stuck together.” “They moved quickly and deliberately over and around one another. They were not fighting, and they did not seem to be trying to get away from us or anything else.” Ashley asks her grandmother what the snakes are doing. “They’re loving each other, baby,” says the grandmother. She then pours lighter fluid into the hole, lights a match, and the snakes start to burn. “The snakes did not slither away or thrash around as they burned. They held each other tighter. Even as the scales melted from their bodies, their inclination was to squeeze close to the other snakes wrapped around them. … They did not panic, they did not run.” The grandmother takes Ashley’s hand and tells her that it’s time she returns to her mama’s house (not an easy place to survive, we discover). Ashley and her grandmother stare into the hole, watching as the snakes burn to death. “These things catch fire without letting each other go,” says the grandmother. “We don’t give up on our people. We don’t stop loving them.” She looks into her granddaughter’s face, “her eyes watering at the bottoms. ‘Not even when we’re burning alive.’” This is a memoir about love and loving, forgiving and not forgiving. It’s written from the heart, and well worth your time.

Somebody’s Daughter, a memoir by Ashley C. Ford, begins with a haunting frontispiece by Izumi Shikibu: “Although the wind blows terribly here, the moonlight also leaks between the roof planks of this ruined house”—followed closely by a letter to “Ashley” from “Dad,” in which we learn that the latter has been incarcerated for 20 years and has only recently received a letter from his daughter Ashley, who is no longer a little girl, but a woman. He tells her she will always be his favorite girl, that he is grateful to be her father and wants desperately to be forgiven for all the pain he has caused her, that he is going to create a beautiful life for himself and is planning to show Ashley and her brother how much he loves them, and that…he is coming home. This book is riveting, emotionally jarring, honest and affective. One memorable and telling scene takes place when Ashley and her grandmother (a refuge for Ashley in the storm of her young life) are standing together in the area beyond the grandmother’s backyard “where my great-grandfather let the grasses grow long.” Ashley’s grandmother takes a shovel and digs a hole in the soft ground. In the hole are a bunch of garden snakes “in some sort of a knot, though not stuck together.” “They moved quickly and deliberately over and around one another. They were not fighting, and they did not seem to be trying to get away from us or anything else.” Ashley asks her grandmother what the snakes are doing. “They’re loving each other, baby,” says the grandmother. She then pours lighter fluid into the hole, lights a match, and the snakes start to burn. “The snakes did not slither away or thrash around as they burned. They held each other tighter. Even as the scales melted from their bodies, their inclination was to squeeze close to the other snakes wrapped around them. … They did not panic, they did not run.” The grandmother takes Ashley’s hand and tells her that it’s time she returns to her mama’s house (not an easy place to survive, we discover). Ashley and her grandmother stare into the hole, watching as the snakes burn to death. “These things catch fire without letting each other go,” says the grandmother. “We don’t give up on our people. We don’t stop loving them.” She looks into her granddaughter’s face, “her eyes watering at the bottoms. ‘Not even when we’re burning alive.’” This is a memoir about love and loving, forgiving and not forgiving. It’s written from the heart, and well worth your time.

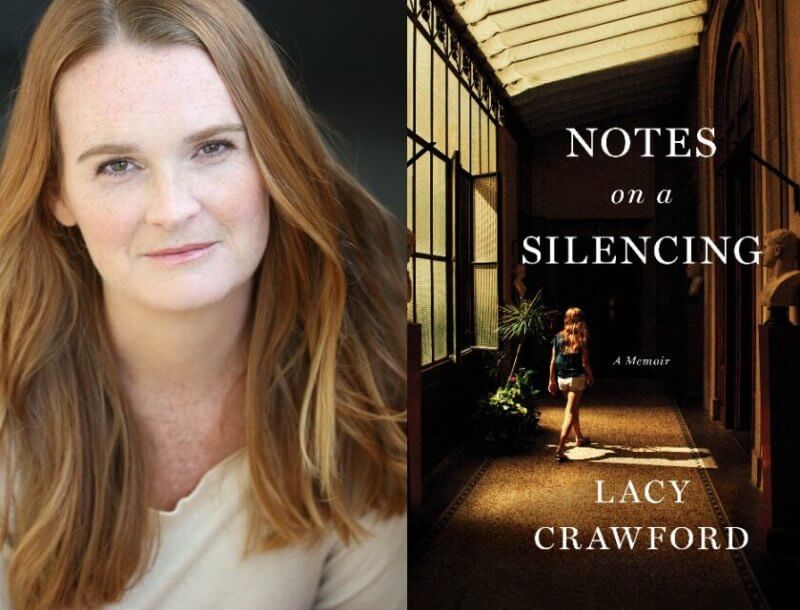

Another memoir, recommended to me by a friend, is Notes on a Silencing by Lacy Crawford. “Brutal and brilliant,” said the New York Times Book Review, and I would have to agree. This book tells the (true) story of a sexual assault on the campus of St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire in 1990. Lacy was the girl it happened to. Initially we hear her story in the third person. “One evening around 11 o’clock, a  young man called a girl on the phone.” And so it begins. This book is not for sissies. To read it is to walk through the shock, horror, shame, sadness and isolation experienced by its author. Again…not for the faint of heart. The writing is excellent—descriptive and evocative, yet spare. This is a memoir that looks one straight in the eye. No flinching. It manages to evoke compassion and sadness for the innocent, hardworking, well-intentioned boarding school student we meet on page one, as well as burning outrage at the ensuing cover-up and the outlandish series of lies and betrayals that emanate from almost every corner when details of the assault threaten to come to light. Sometimes this book reads like a diary, in which the reader joins the author in her innocence and utter lack of preparedness for an assault of this magnitude—sometimes like good, piercing journalism that focuses, brave and laser-like, on the frightening ways institutions, government and society tend to silence victims and distort truth to preserve their reputation and standing.

young man called a girl on the phone.” And so it begins. This book is not for sissies. To read it is to walk through the shock, horror, shame, sadness and isolation experienced by its author. Again…not for the faint of heart. The writing is excellent—descriptive and evocative, yet spare. This is a memoir that looks one straight in the eye. No flinching. It manages to evoke compassion and sadness for the innocent, hardworking, well-intentioned boarding school student we meet on page one, as well as burning outrage at the ensuing cover-up and the outlandish series of lies and betrayals that emanate from almost every corner when details of the assault threaten to come to light. Sometimes this book reads like a diary, in which the reader joins the author in her innocence and utter lack of preparedness for an assault of this magnitude—sometimes like good, piercing journalism that focuses, brave and laser-like, on the frightening ways institutions, government and society tend to silence victims and distort truth to preserve their reputation and standing.

Crawford’s writing is at once chilling and crystal clear, her witness compelling and (for me) unforgettable. I am a graduate of another equally elite northeastern boarding school, and so I was particularly struck by some of the details of Crawford’s account, while being haunted, saddened and sickened by her school’s unwillingness/inability to support her. One comes to wonder how Lacy Crawford even survived this ordeal. And one can’t help but blanch at this boarding school’s failure to hear, nurture and protect this student in their care.

At one point, Crawford speaks of a stained-glass window in the school’s chapel (we had one, too) with biblical script that read, “Now get up and go into the city and you will be told what you must do; the knowledge of the secrets of the Kingdom of God has been given to you.” (I know those stained-glass windows, those biblical directives.) “I liked to think there was a direction for me,” writes Crawford, “however much solitude it might demand, however much loneliness.” A book for our time. Don’t miss it.

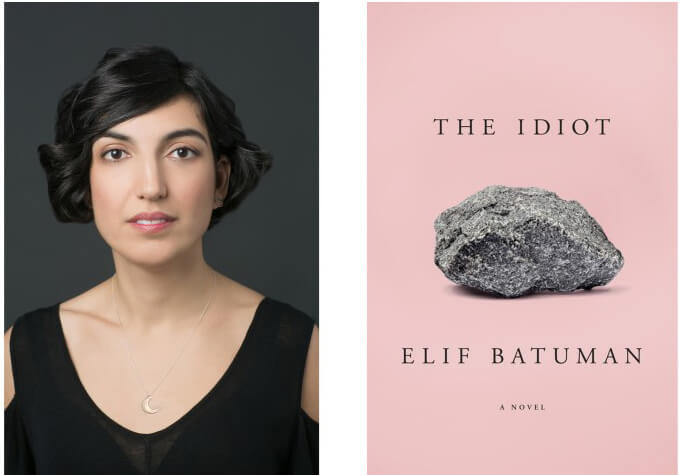

My book group was iffy about a recent read, The Idiot by Elif Batuman, but in the end, I would have to say I really loved it. It’s a strange book, not exactly funny, but not exactly un-funny either. “Dry” might be a good word to describe it.

My book group was iffy about a recent read, The Idiot by Elif Batuman, but in the end, I would have to say I really loved it. It’s a strange book, not exactly funny, but not exactly un-funny either. “Dry” might be a good word to describe it.

Basically, The Idiot is about Selin, a daughter of Turkish immigrants, and her freshman year at Harvard. It is a rather (yes) dry, bizarre and somewhat bewildering romp. There’s kind of a romance involved, but is it a romance? I’m not entirely sure, nor (I think) is Selin herself. But she gives herself to it, kind of, mostly through language, writing, and a few tepid, rather unsatisfying, and sometimes quite amusing (to us, not her) encounters. There are a lot of emails, misunderstandings and miscommunications, along with a trip to the Hungarian countryside.

Maybe the frontispiece by Marcel Proust says it best: “But the characteristic feature of the ridiculous age I was going through—awkward indeed but by no means infertile—is that we do not consult our intelligence and that the most trivial attributes of other people seem to us to form an inseparable part of their personality. In a world thronged with monsters and with gods, we know little peace of mind.”

“Adolescence,” concludes Proust, “Is the only period in which we learn anything.”

It’s an interesting idea. Not true for me, personally, as I do believe I am still learning—though I suppose one might argue that, in fact, I am, though in my early 60s, in a delayed, prolonged adolescence, which would make it quite true, hmm, I will have to think about that. But nevertheless, an interesting quote, especially considering the lives and stories of the three protagonists described above.

Perhaps Proust is off, and adolescence isn’t the only period in which we learn anything. But it certainly is a rich, bewildering, intense and fertile time in the human lifespan—a time rich with learning experiences, certainly. In any case, these three memoirs do a stunning job of conveying some of its struggles, lessons, loves and heartaches, and some of what it feels like to be young and fairly new in this dizzyingly beautiful and damaged world.