The importance of forest legacies

Forests are communities, a rich mixture of organisms engaged in relationships and interactions with each other, built around the living architecture of trees. These communities parallel healthy human communities in many ways, not because they are simple and uniform but because they are messy, dynamic, diverse and interconnected, engaged in a complex process of renewal and change that will never be completed.

Being responsible stewards of our forests forces us to take the long view, as the life span of a single generation of trees may exceed ours by centuries. Responsible forest stewardship is about building a better world for countless future generations of people and for the thousands of species that make up our forests, the millions of organisms present in a handful of forest soils. The imprint that we leave on our forests, as in our human communities, is our legacy.

Being responsible stewards of our forests forces us to take the long view, as the life span of a single generation of trees may exceed ours by centuries. Responsible forest stewardship is about building a better world for countless future generations of people and for the thousands of species that make up our forests, the millions of organisms present in a handful of forest soils. The imprint that we leave on our forests, as in our human communities, is our legacy.

The forests of Vermont are infused with the legacies of the past. Nearly all of them were cleared in the 1800s, some maintained as agricultural land for a century or more. While about 75 percent of Vermont is now forested, most of our forests are still in recovery, dramatically shaped by this clearing. Today, Vermont’s forests are generally much younger, less diverse and less complex than the forests that covered our state just a few centuries ago.

Like human communities, forests are multi-generational. While many of Vermont’s forests are currently dominated by a single generation of trees (which took root in abandoned fields), this is a temporary condition. Over decades or centuries, the uniformity of these simple forests will break down, tree mortality—death—allowing new generations of trees to establish and grow among the old.

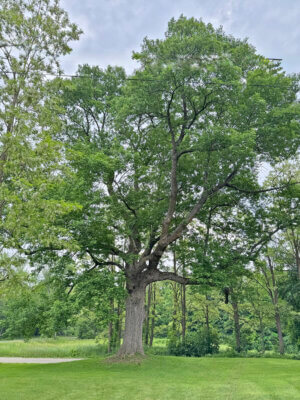

Also like our communities, forests leave legacies for future generations. The remnants of trees and forests of the past are what foresters and ecologists call “biological legacies.” Biological legacies may be as obvious as massive “wolf trees” or as subtle as rich soil, built on the organic material from trees long since gone by. Over time these legacies make forests richer, more diverse and more resilient, broadening the range of habitat niches available for a wide variety of organisms and buffering them against forest health threats.

To some, biological legacies may seem like a waste; our intuition tells us to value simplicity, regularity and productivity over complexity and diversity. For example, large, old trees are sometimes called “decadent” and killed to make space for younger, more valuable “thrifty” trees. Like the elders in our human communities, while old trees may not be the fastest, most efficient or most productive ones in the forest, they enrich our world in countless ways. Among other benefits, old trees provide unique habitat for wildlife, invertebrates (bugs), mosses and lichens, fungi and other microorganisms that don’t associate with younger trees. They are hubs in complex underground “mycorrhizal” networks in which fungi link trees together, allowing them to communicate and share resources. These connections make forests more resilient and healthier in the long-term.

How do we bring these lessons about legacy into the management of our forests? We need to recognize the importance of creating and maintaining biological legacies, leaving some big trees and lots of dead wood in the woods, modeling our management on the way that forests naturally grow and develop, and striving to create forests that are complex and multi-generational. We need to re-train ourselves to value diversity and complexity over simplicity and productivity.

How do we leave a better legacy for the future? In our forests, as in our human communities, we don’t get to choose the legacies we inherit; the only choice we truly have is what we’re going to do about it. When I bought my land in Bolton, I took on the legacy of centuries of mismanagement, an unhealthy forest infested with non-native invasive plants and affected by a local over-population of deer. I inherited a changing climate, an increasingly fragmented landscape and the persistent effects of non-native invasive pests and pathogens like the emerald ash borer, Dutch elm disease, beech bark disease and more.

I can complain about how these problems aren’t my fault, or I can take responsibility for the world we have and work hard to leave a better legacy for future generations.

Ethan Tapper is the Chittenden County forester. He can be reached by email or by phone at (802) 585-9099. Sign up for his email list or see what he’s been up to at here.

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair