Brood—more than just chickens

I have never owned chickens. And I’ve not been tempted to do so until recently, when it seemed that every third person I knew was getting them. It wasn’t just my imagination, for indeed, during the coronavirus pandemic there has truly been greatly heightened interest in raising chickens. Take it from Nancy, owner of the Cackle Hatchery in Lebanon, Missouri, which has been swamped with orders: “We can’t answer all the phone calls, and we’re booked out several weeks on most breeds.” Seems there are two main reasons for the surge, both pandemic related. One, with food availability not always a sure thing, chickens give people more food security. And two, spending so much time at home, often with kids, what else are we supposed to do? I mean, why not get chickens? Which are, interestingly, the exact words my son Dylan used during the early days of COVID. He kept at it until I sagely reminded him that no one in our household eats eggs. That pretty much shut it down.

I have never owned chickens. And I’ve not been tempted to do so until recently, when it seemed that every third person I knew was getting them. It wasn’t just my imagination, for indeed, during the coronavirus pandemic there has truly been greatly heightened interest in raising chickens. Take it from Nancy, owner of the Cackle Hatchery in Lebanon, Missouri, which has been swamped with orders: “We can’t answer all the phone calls, and we’re booked out several weeks on most breeds.” Seems there are two main reasons for the surge, both pandemic related. One, with food availability not always a sure thing, chickens give people more food security. And two, spending so much time at home, often with kids, what else are we supposed to do? I mean, why not get chickens? Which are, interestingly, the exact words my son Dylan used during the early days of COVID. He kept at it until I sagely reminded him that no one in our household eats eggs. That pretty much shut it down.

But I am not a stranger to chickens. In fact, I grew up with them. Though the chickens were not actually mine. Rather, they belonged to my sister Sharmy. What happened was, when my family built a barn on our property, back when I was like 12, we kids were told that we could each choose an animal to raise. This was beyond exciting. I wanted a cow but ended up settling on goats. Dinah, who had for years wanted a monkey, chose a pig. And Sharmy, the youngest—well, you know where this is going—Sharmy was kind of coerced into choosing chickens. I think the truth of the matter is, my parents wanted eggs. So…while Dinah and I were snuggling with Millie and Piggy, Sharmy was doing her darnedest to bond with six Araucana chickens. I don’t remember her ever complaining, though in hindsight that is a little hard to fathom. The eggs were nice, once they were cleaned (they came in different colors), but her chickens never struck me as particularly friendly. I would say that last bit is an understatement.

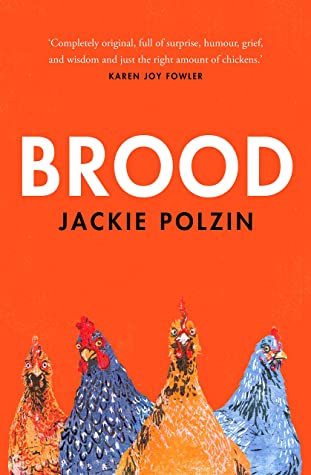

If Brood by Jacki Polzin hadn’t been chosen by my book group, I probably wouldn’t have picked it up. But that would have been a tremendous loss for me. Though it reads like a memoir, Brood is a novel. But you forget that, because it so subtly, delicately and effectively evokes the person of the narrator, whose name we never learn but whose soul is somehow dimly yet profoundly exposed to us over the course of a year of tending to a small brood of chickens. Which, I get it, might strike you as less than scintillating. But I honestly couldn’t put this book down. Not because it’s a thriller but because it is enchanting and, in a uniquely gentle and unassuming way, pulls you in. Brood has been compared to H is for Hawk and Gilead, but to me it is more reminiscent of Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteredge—because of the way the narrator has such a distinctive voice and presence and, like Olive, is crusty, laconic, obdurate, uncordial, yet heroic—and because, like Strout’s later novels, Brood reads almost like poetry. One wants to read it slowly, savoringly.

I guess if you have a tender heart, raising chickens is not always easy. It certainly wasn’t easy for Brood’s narrator, in Minnesota, where winters are colder than cold and summers sweltering. Plus, there are predators, disease, bad luck and intra-chicken dynamics, which can be brutal. “Life,” writes Polzin, “is the ongoing effort to live. Some people make it look easy. Chickens do not. Chickens die suddenly and without explanation.” Though this may sound flippant, this chicken tender is anything but. She becomes profoundly connected to her brood. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say: she loves them like family.

When I first began this book, I thought it was going to be funny.

“Here,” I placed the fair egg … in Helen’s palm. Her fingers did not soften to the shape. “What should I do?” she asked.

“Cook it, eat it,” I said.

“I mean now. What should I do now?” She did not hold the egg but allowed the egg to rest on her flat hand, was only tolerating the egg for, I suppose, my benefit. The egg was not especially clean. The cleaner an egg looks, the more likely a visitor will accept the egg with grace and hold it in a manner befitting an egg, a force equal but opposite to the weight of the egg applied by a cupped hand, creating perfect balance and suspension in midair.

“Is it cooked?” she asked. “It’s warm.” She had seen me retrieve the egg from the straw, the straw worried down and out and up at the sides in the precise counter-shape of a nesting chicken, a bed of straw so primitive as to predate fire, and yet she wondered out loud.

“It’s fresh,” I said. “It’s warm because it’s fresh.”

“Has an egg ever hatched in your hand?”

Though this book is, yes, wryly funny on occasion, there is longing and sadness clucking softy between the lines. Relationships with humans are scanty, but much is suggested. And there is a deep, echoing, almost aching intimacy evoked by the narrator’s musings on home, coop, work, marriage and loss, and in the hint of hope for what is yet to be known and lived.

This book is brilliant. Heartrending, compelling and poetic, I didn’t want to part from this nameless woman and her backyard brood any more than she wanted to part with her four feathered charges. Like a Japanese ink painting, much is conveyed by few strokes. This book is about a lot more than chickens.