A tree’s second act

Somewhere encoded into our DNA is an appreciation for forests with evenly spaced, uniformly sized trees and a completely bare understory. If you identify with that idyllic vision, you’re not the only one; most landowners I meet picture healthy forests in that way. I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard someone talk about “cleaning up” their woodlot, which usually means removing fallen and dead-standing trees, as well as any other trees that may seem unruly or out-of-sorts.

Unfortunately, this vision of a “well-managed” forest is not what healthy forests actually look like. “Messy” forests, those with many different species, ages and sizes of trees, interspersed with dead-standing and fallen trees, feature better wildlife habitat, improved forest health and resiliency and improved carbon storage capacity, among other benefits. As people who own, manage and appreciate forests it is important to understand that “messiness” is a condition of vibrancy and health—and one that is closer to conditions found in late-successional or “old-growth” forests—and not a reflection of poor forest management. For this article, I want to emphasize the crucial role that dead wood (also called “woody debris” or “dead biomass”) plays in healthy forests, from supporting forest health, growth and development to wildlife habitat and carbon storage.

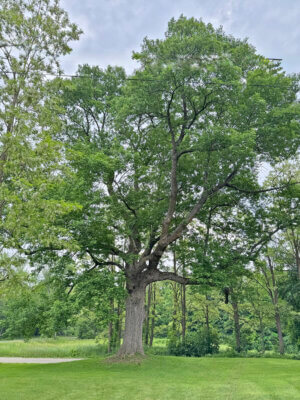

While dead trees may seem to be have served their purpose, the ecological “life” of a tree actually extends far beyond its “death.” The second act of a tree often begins when it transforms into a “snag,” or “dead-standing” tree. Insects and fungi colonize the snag, gradually breaking down the wood, and woodpeckers excavate “cavities” in their search for food. These snags and cavity trees teem with life, providing nesting habitat for birds from chickadees to owls and den sites for animals from flying squirrels to porcupines.

When a tree or snag falls to the ground it becomes an important habitat for more mammals, insects, reptiles, amphibians and fungi, in addition to providing a moist, rich place for trees and plants to grow. Some species of trees, like yellow birch, are especially adept at rooting on these “nurse trees.” As wood decomposes over time, it releases nutrients that can be taken up by living trees and plants, holds moisture, stores carbon, mitigates erosion and generally supports the health and fertility of forest soils.

Compared to old-growth forests, forests in Vermont generally lack dead wood. This isn’t solely the fault of current land management practices; the wholesale clearing of land in Vermont in the 1800s essentially hit the reset button on our forests, undoing thousands of years in which forests were increasing in complexity and diversity and accruing dead wood. The forests that regenerated following field abandonment in the early-mid 1900s are very different from those that may have been found in Vermont 400 years ago, including having much less dead wood.

When we manage forests actively, we make some compromises in the name of harvesting a local, renewable resource, including cutting and removing trees that would eventually become dead wood. Fortunately, there are ways to minimize the negative impacts of this.

First, leave fallen and dead-standing trees alone. Focusing your attention on cutting unhealthy standing trees, especially those competing with your best stems, is a better use of your time.

Second, whether you’re cutting firewood for yourself or engaged in commercial forest management, leave as much wood on the ground as you can. This is especially true for the tops of trees, which most loggers don’t utilize anyway. These tops provide all the benefits of dead wood, including excellent wildlife habitat and protection for young trees from deer browse. Embrace the “messiness” and leave the tops as they fall, rather than cutting them up, for maximum benefits.

Finally, leave some “biological legacies”—trees that are allowed to live out their days without ever being cut. These trees will provide wildlife habitat, ecosystem benefits and eventually dead wood.

Managing healthy forests requires expanding our idea of what forests are and the factors that contribute to their health and productivity. While it may seem counterintuitive, dead wood in our forests is critical to their long-term health. So, the next time that you see a fallen tree in the woods, rather than despairing or cutting it up for firewood, take a moment to appreciate it for what it is and let it live out its second act.

Ethan Tapper is the Chittenden county forester. He can be reached via email, by phone at (802) 585-9099 or at his office at 111 West Street, Essex Junction.

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair