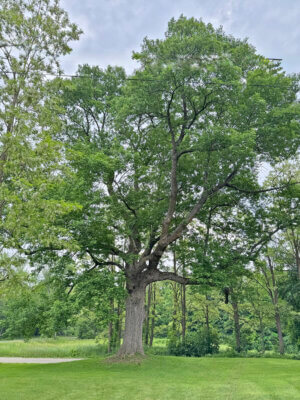

Into the woods – Resilience

When trying to manage for healthy forests, you must first consider how to gauge forest health. After all, if we don’t know what condition we’re shooting for, it’s hard to know when we’re headed in the right direction. Is a healthy forest, one filled with trees growing quickly and efficiently? Or one without disease? Does it include high-quality wildlife habitat, or should forest health be measured solely on the condition of trees?

While foresters and scientists have scratched their heads over this for a long time, the best answer we have is that forest health is determined by a quality that is difficult to measure or quantify. This quality is called “resilience.”

While we are often hyper-focused on the trees in our forests, trees are just one part of a vastly complex and inter-connected system. The more we learn about forests, the more we understand that “non-tree stuff,” like wildlife, plants, insects and pollinators, soil microbes and fungi, all play critical roles in keeping them healthy. Accordingly, even if you are mostly concerned with just managing trees, you should consider a more holistic approach when thinking about forest management strategies.

Following the wind storm last October, I was inundated with calls from landowners deeply concerned about the health of their forest, heartbroken at the death of trees they had watched grow for decades and by seeing their yard or woodlot drastically changed. However, from my perspective this event was an opportunity to explain an important concept: that disturbance and change are necessary and inevitable processes in our forests, and that these processes are part of how they remain vibrant, diverse and healthy over time. The question is not if disturbance is part of healthy forests, but how forests respond to these events, which is where “resilience” comes into play.

The resilience of a forest can be defined as its ability to respond to disturbance while maintaining its productive capacity. The trees, plants, wildlife and other species that make up our forested systems have evolved while dealing with constant change and disturbance. These species, functioning as systems, have developed means of retaining and enhancing the fertility of their environment, even in the face of catastrophic disturbance. This is most obvious in forests’ ability to protect the productivity of their soils but could also be extended to include their ability to resist infestation by diseases and invasive species, to offer habitat to a wide range of native flora and fauna, and to offer a continuity of ecosystem services like clean air, clean water and carbon storage.

One can observe the resilience of forested systems by observing how forests respond to disturbances, from the death of a single tree to a large-scale blowdown. Disturbances create conditions that trigger new growth and regeneration, with different tree species responding to fill each niche. This regeneration stabilizes and protects soils and their vital nutrients that would otherwise be lost in the course of this disturbance. At the same time, they provide new habitat for wildlife and future generations of trees. This process is continuous—a forest is dealing with some degree of disturbance at all times.

So how can we manage for resilience? As I have said in this column many times, the answer is diversity, diversity, diversity. Forests with a diversity of tree species can respond to a wide range of pests, pathogens and environmental conditions. Similarly, forests with many different sizes and ages of trees are able to respond vigorously to disturbances affecting a single age class of trees, such as a wind or ice event that can remove the forest’s overstory. Encouraging the forest’s “weirdness” (diversity) is critical and should be coupled with removing factors that interfere with the forest’s ability to respond to disturbance, such as removing invasive exotic plant species and taking steps to limit over-browsing by deer.

The final piece of managing for resilient forests is achieved by keeping them forested and whole; parcelization, fragmentation and development limit forests’ ability to remain healthy and our ability to manage them. Conserving your forest land, making a succession plan to ensure that your forest persists after your time, and advocating for protecting forest resources and intact forest blocks in the course of development are all ways to keep our forests growing, changing and remaining healthy into the future.

Ethan Tapper is the Chittenden County forester. He can be reached at (802) 585-9099, by email, or at his office at 111 West Street, Essex Junction.

Related Stories

Popular Stories

If you enjoy The Charlotte News, please consider making a donation. Your gift will help us produce more stories like this. The majority of our budget comes from charitable contributions. Your gift helps sustain The Charlotte News, keeping it a free service for everyone in town. Thank you.

Andrew Zehner, Board Chair