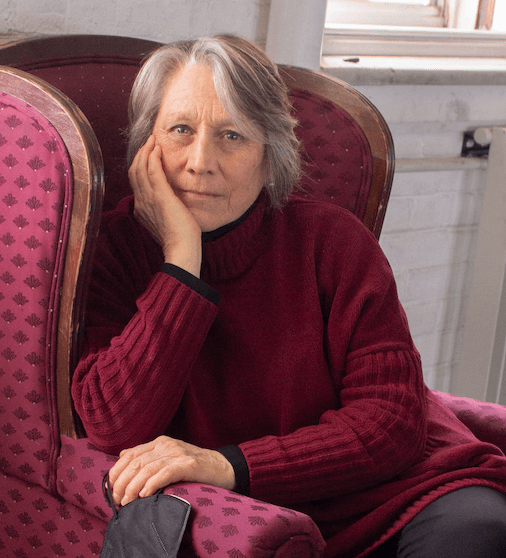

Cameron Davis: The intersection of art and the environment

Cameron “Cami” Davis has always painted but her art has evolved over the years. She described her first 25 years of work as non-objective, but after taking classes in ecological theory at Schumacher College in 1998, she changed her perspective.

“Now I intentionally look at the dynamic between something recognizable and the form that I feel,” she said. “It’s almost left brain/right brain. Essentially a painting is a visual conversation.”

Cami Davis uses her art to make sense of the presence of nature.

Davis is a member of the Eco Art Network, which she described as an international dialogue group of artists, curators and cultural theorists who explore human-nature relationships.

“I work in a traditional medium,” Davis said, “but I use the language of painting to make sense of how I perceive nature, explore definitions of what is nature and how humans are located within life.”

Although her work has become more representational, one thing that hasn’t changed is Davis’ attempt to connect and make sense of the presence of nature.

“Many children have the feeling of a dissolved ego in nature where you’re at one with everything,” she said. “When I was little, I had one of those moments out in the woods spinning and making up a song. I ran inside and picked out the notes on the piano and wrote down the notation. I don’t know why I wanted to give form to that experience, but a similar impulse brings me into the studio today.”

After graduating from the University of Vermont with a degree in studio art, Davis got her Master of Fine Arts at Pratt Institute, following that with postgraduate work at Schumacher College, where she studied psychology, ecology and art.

“It all ties together,” she said. “The college is known for holistic studies. All their courses deal with inside-outside perception.”

Davis recently retired from the University of Vermont, where she spent 34 years teaching painting and drawing with the Department of Art and Art History. She was also an environmental program affiliate and taught cross-listed classes which combined philosophy, ecology and art, requiring students to reference environmental issues like climate change and social justice.

“We tend to separate into all these silos,” Davis said, “but we’re in a time period where that habit of thought is appropriately unravelling. The arts have always employed this relational thinking and are an important place to flex this perceptual muscle.”

Davis served on the steering committee of the University of Vermont EcoCulture Lab, a collaborative effort among artists, humanists, scientists, designers and others to address ecological challenges. She is proud of her work for the lab’s Feverish World Symposium which had participants from University of Vermont, Champlain College and St. Michael’s College in what she described as a huge freewheeling event with international speakers, student artwork and musical performances around climate change and social issues.

Davis was an alpine ski racer in high school, but knee issues forced her out of the sport. She spent a year coaching ski racers at Green Mountain Valley School, but her heart wasn’t in it, so she took a train to Alberta, Canada, for an artist residency at the Banff Centre for the Arts.

“I painted 14 hours a day,” she said, “and got an idea of where I wanted to go with painting.”

Davis has also attended several Vermont Visual Artist residencies at the Vermont Studio Center.

Davis is taking advantage of her retirement to work on two major projects. One is a body of new paintings exploring what she describes as “EcoConsciousness.”

The second will be a digital stage set for a performance of the Emergent Universe Oratorio at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center in Troy, N.Y. The set will be a projection of details from her paintings with animated elements.

“It’s an amazing opportunity,” she said. “It’s exciting new territory, a bit scary, but less so as I put one foot in front of the other.”

Davis describes painting as a practice of “making sense of, and in, the world.” Although her paintings deal with difficult issues like climate change, she sees her work as both a process of grieving and a way to connect with presence, which she said might even be described as love.

“Beauty is an entry point into feeling grief, and presence signals a kind of wayfinding in the painting process shaping many of my decisions,” she said. “The finished painting becomes the temporary resolution of that conversation; full of emotions, ideas and responses, including a kind of surrender to the material, optics and surprising insights. In this way, wrestling with the difficulties of that illusive notion of making a painting work can also have moments of joy.”