November Reflections

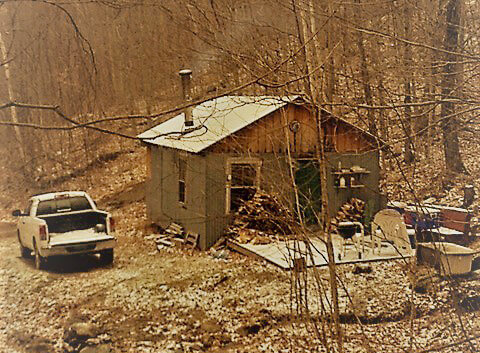

It seems that every November my spirit longs for a simpler life. The stark barren trees seem to strip off all unnecessary accoutrements of modern life. It’s a time of deep reflection and inner contemplation of our place here on this earth. If it appears that all this life offers is rewards for acquiring titles, possessions and money, we are missing the point. In November, the leaves tell us that the accumulation of these ideals can be shed in a moment when a cold north wind rips through our souls and we learn that they are not the substance of life that we all really wish with which to connect. My drive to deer camp for Opening Weekend of the traditional rifle season for deer (it’s always 12 days before Thanksgiving—this year it will be Saturday, Nov. 13) is one of great excitement. To walk through the denuded woods, sprinkled with the season’s first light covering of snow, is to relieve my spirit of the human belief that we need more than shelter, warmth, water and food.

My heart returns to the most intrinsic appreciation of what it is to hunt. To be alive and recognize that the elements I embrace have no more concern for my life than that of any other animal roaming the wilderness. I am on equal footing with Mother Nature. Clutching my rifle gives me the comfort of being able to defend myself or seek to participate in the Circle of Life by seeking another being to feed my body and spirit. For many, it is hard to understand how hunters can love the animal they seek to kill. This perception is too simplistic, for it is not about the kill. The hunt leads us to a deeper understanding of the animal—how, where and when it feeds, sleeps, and seeks shelter the same as the hunter. The grace and majesty of a big buck cannot be overstated. To get a glimpse of such a magnificent beast requires that we understand the life of such. We study them. We study their tracks, their preferred travel routes for each of the wind directions, what the preferred food source is based on the crop of nuts, apples and grasses and when each of those is the most attractive. Examining each type of acorn, which ones are most abundant and where they are located, will lead us to learn that the white acorn is more attractive than the red variety.

And then there is “the rut.” This mating ritual occurs each year, triggered by the lunar position, the amount of daylight each day, and the rising hormonal traits of each doe that is old enough to be bred. The buck will frequently alter his patterns to pursue the doe for three to four days, waiting for her to ovulate, giving off a time sensitive scent that signifies it is time to breed. The buck will deny his other instincts—finding food, finding shelter, even sleep to chase and breed as many does as he can in this brief period. The rut has three stages or peaks. The first is usually around the second or third weeks of October. The second peak coincides with the rifle season around the second and third weeks of November. This peak is the strongest. The third peak occurs in December during muzzleloader season.

When I have taken a buck from our camp, I stay with it as it passes into the next realm, praying for forgiveness. I put a sprig of cedar in its mouth as its last meal and express gratitude to the Great Spirit that the energy of grace and acceptance pass from this being into my own. I promise the departing spirit that I will honor and cherish the flesh to be shared with those people I love. I am very particular about who I share with. If they can respect the deeply spiritual gesture of serving venison, I will prepare the meal in the most thoughtful and compassionate manner I can. Those who will not understand or accept this path will be respectfully not invited.

As I sit in front of the woodstove on the evening of Friday, Nov. 12, I will meditate on the next morning. I will walk down to the lower logging trail, then cut up into the recently cut timber. I will climb up the small ravine that acts as a funnel for deer travel, and in the dark, will try to locate the young pine tree with the little tunnel behind it. The first time I was looking for a stand I was “invited” into this shallow hidden divot by a snowshoe rabbit who scurried down the hole. He was my spirit animal that day, and I was blessed to witness a gorgeous 10-point buck that was out of range. After the big buck left, a small four pointer walked in front of me and stood there waiting. This is what the natives call “presenting.” It is when an animal offers itself to you. The spirit of such an unselfish gesture is a blessing and is not to be ignored. It is moments like this that bind me to my nature. Whether we choose to capture its essence with a camera, or a rifle is a choice, both of which are honorable and should be accepted with gratitude.

May the Great Spirit bless you with the understanding of why hunters seek this connection.

Bradley Carleton is Executive Director of Sacred Hunter, a nonprofit that seeks to educate the public on the spiritual connection of man to nature.