The last pizza on earth

Pizza on Earth, the pioneering establishment that brought artisanal wood fired pizza to Vermont, served its last made-to-order creations on July 23. Owners Jay and Marcia Vogler, both 66, haven’t decided whether the closure will be permanent, but they say it’s time for an extended break after “10 years of farming and 22 years of pizza-ing.”

The couple alerted the community of their plans several weeks before the closure, and customers flooded the phone line on the last morning they were taking orders. It took just 50 minutes to sell out the 100 available pizzas, leaving many longtime customers frustrated. “We had a lot of swearing the other day,” Jay noted wryly. “One of our regulars from Hinesburg got the last Pizza on Earth and he said that will go down in the history books.”

That regular, Tom Barden, is still processing the news. “I’m from Ireland and I Zoom with my still-living siblings in Ireland and they knew that we had pizza every Friday. They asked me what I’m going to do now and I said, well, I’m going to starve.”

The Voglers moved to Charlotte from New Jersey in 1991. In the beginning, it was farming, not pizza, they focused on. Jay, a chef who had apprenticed on an organic farm in New Jersey, ran the 64-acre Bingham Brook Farm while Marcia continued to work fulltime as a bra and lingerie designer. And just as Pizza on Earth would eventually pave the way for other wood fired pizza purveyors, they also helped build the culture of organic farming in Vermont. “When we moved here, we were one of 60 organic farms in the state; now there are 700 or more,” Jay noted.

They evolved from a largely wholesale farm to one that for a time featured a CSA. Pizza came into the picture after they installed a commercial bread oven in the late 1990s. Since people were coming to pick up their CSA shares, they reasoned, why not also offer pizza? “The first year I’d be farming and then I’d run in make the dough and everything and go back out, and maybe we’d sell eight or 10 pizzas,” Jay recalled.

That changed when Seven Days cofounder Paula Routly and columnist Debbie Solomon began writing about the mouthwatering, thin crust pizza Jay made with the farm’s and other locally sourced fresh organic ingredients. By 2001 they stopped farming to focus on pizza and were regularly selling up to 120 pizzas each night they were open, along with several types of bread and Marcia’s cakes, tarts, cupcakes and gelato. “I don’t know why we did that,” she admitted, shaking her head as they recalled their ambitious offerings.

“To show we could,” Jay interjected.

Marcia, who quit fulltime work in 2006, recalled that casual dining and takeout options around Charlotte were limited 22 years ago. “People starting talking about how they needed a place to meet in the community,” and their Hinesburg Road farm became that spot. It regularly drew families with children, out of town visitors and anyone who wanted to enjoy exceptional pizza and desserts on the wooden picnic tables scattered in front of the farmhouse.

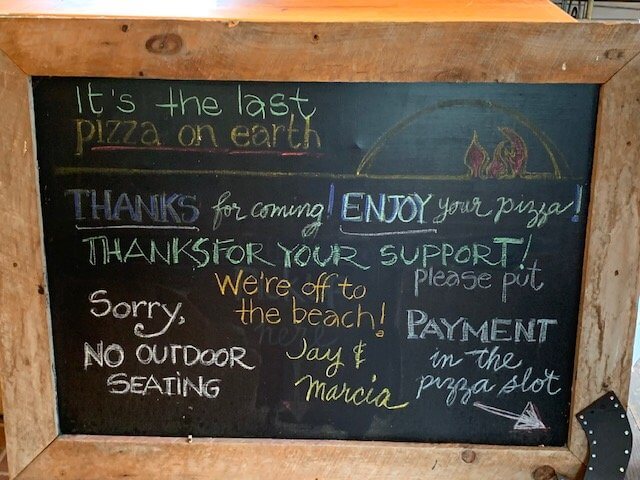

The roughly four days of preparation required to make the pizza and its changing ingredients, the hard physical work, and the nights when guests sat on their front lawn until 10 o’clock took their toll over the years. And though the business always had a loyal following, competition from as many as eight other establishments that now serve pizza within 10 miles highlights how much the food landscape has changed since 1999. Covid forced the couple to rethink their model, first shutting it down entirely, then eliminating paid staff and paring back to takeout only. Surprisingly, Jay and Marcia found they liked the change and weren’t ready to return to the old way. Of their decision to close now, Marcia explained it this way: “We want to just regroup and think about what it is we want to do, and if it is keeping the same model or not doing it at all.”

On an eerily quiet Friday morning when the phone would normally be ringing with orders, the pizza shop was dark and the oven, cold. As they reflected on what might come next, both Jay and Marcia said it was too early to know. They mentioned simple things like cleaning the barn, climbing Mt. Mansfield, which they’ve never had time to do, spending more days at their lake cabin in Cornwall, and having more time for artistic endeavors. “I’ll be painting more,” Jay said, and Marcia, who is also a guide at the print shop at the Shelburne Museum, is learning letterpress printing.

Both of them shake their heads when asked if they intend to rest. Whatever comes next, it won’t be sitting still. “That’s not what we would do,” Marcia says firmly.

Jay agrees. They’ve kept their food license and rather than shutting down or selling off their equipment, they’ve hung a Closed sign for the time being. “If we think it’s a mistake, it’s here to redo.”