What’s in the Charlotte Museum?

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Charmingly diverse collection brings rich history to life

It’s a heavy, round black iron ball, about the size of an orange. The ball sits silent and unmoving on the glass countertop at the Charlotte Museum.

“Grapeshot,” says Dan Cole, local historian and president of the Charlotte Historical Society. “During the War of 1812, some Charlotte residents were apparently hollering at British troops sailing up the lake to Otter Creek.” The British troops decided this constituted aggressive action by members of their former colony “and put grapeshot in their cannon and unloaded on the townspeople.”

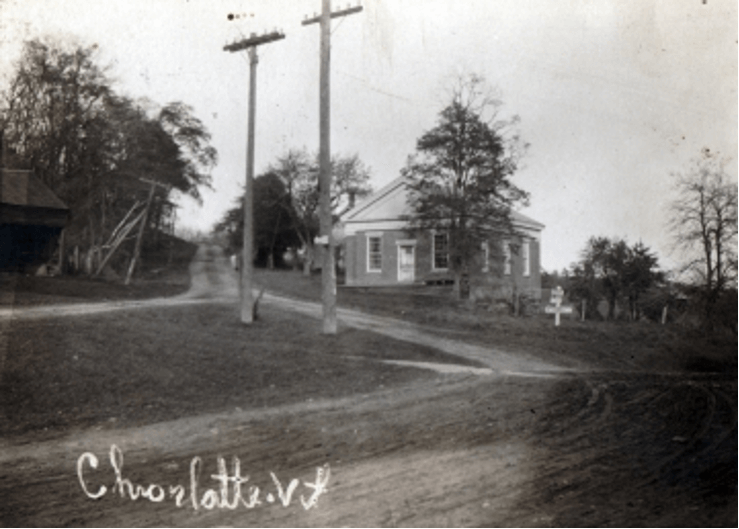

Records show that little damage was done that day, and many of the cannonballs landed in farm fields and emerged at haying time. The museum’s cannonball lives on as part of a diverse collection of historical items and records preserved in the Charlotte Museum, the tiny red brick, Greek Revival building on a small flowered plot at the intersection of Hinesburg and Church Hill Roads.

Preserving items and records that represent and record Charlotte’s history is the mission of the museum. Charlotte Historical Society members manage the museum’s collection, share the history with visitors during a handful of days each year, and help the occasional school child with a report for history class.

“We make ourselves available to pass on history to newer generations,” says Kathleen McKinley Harris, a Historical Society member for four decades. Charlotte’s history is significant, says Harris, “because whether or not we are aware of it we are influenced nearly every day by the rich history that is all around us.”

The museum building sits in a spot that itself is awash in Charlotte history. Dan Cole is happy to take visitors across the small green in front of the museum where he bends back cedar limbs and points out the remains of the town well and pump that created a natural center for the original Charlotte settlement that formed in the area in the late 1700s. He points out the stone steps a few feet north that led at one time to the Washington Hotel, a public house that boasted 10 fireplaces. (In 1948 the tavern was purchased by the Webb family and transported to the Shelburne Museum, where it lives on as the Stage Coach Inn.)

The museum was originally constructed as the Charlotte Town House (i.e., meeting house) in 1850. It sat in the center of what was then a busy commercial stop on the main stage line between Montreal and southern New England and New York. The Town House eventually became Charlotte’s official Town Hall where town business was conducted—although the building was too small to house the town’s records, which had to be carried home at night by the town’s clerks.

Despite being named for Sophia Charlotta von Mecklenburg-Strelitz, England’s queen and wife of “Mad” King George III, the town had an active role resisting the British in the Revolution and subsequent War of 1812. Museum records document Vermont military activity in the surrounding areas—including the sale of property by local heroes (and land speculators) Ethan and Ira Allen to former members of the Vermont military. Charlotte residents in the Allen and Keeler families trace their histories to Ethan Allen.

But with time and commercial expansion as well as a growing population, Charlotte’s focus turned domestic. A current exhibit at the museum documents the growing community’s commitment to education in the late 1800s. The exhibit shows Charlotte divided into 14 school districts in 1880 with 13 common schools (and an annual town school budget of just over $2,100). The exhibit’s shelves include school photographs, class rosters, and textbooks carried by Charlotte’s schoolchildren over the decades, such as Swinton’s Language Primer, its aged pages bound in dusty gold and green leather.

In the late ‘40s, Charlotte Town Hall had moved to a larger building, and the Town House was rededicated as a museum, originally intended to honor armed services members.

Today, the building’s walls and shelves are lined with items ranging from the historically significant to the charmingly ephemeral: From a late 19th Century U.S. flag with 38 stars that flew over Cedar Beach, and photos and paintings of local notables like Louisa Howard Spear to wood taps for syruping, ceramic bottles, sewing supplies, and a Bible carried by Lucius C. Pease in the mid-1800s.

One highlight is a collection of Abenaki baskets and accessories held in its own glass display case. The baskets were made from sweetgrass with split ash and natural dyes by the Obomsawin family on Thompson’s Point. The family, led by Simon Obomsawin, an Abenaki woodsman originally from Quebec, settled in Charlotte in 1875. The Obomsawins made and sold baskets, snowshoes, sleds, furniture and other items to summer campers and local residents. “We’re proud of the Abenaki basket collection,” says Cole. “We believe ours is the best collection in the area.”

Photo credit, “Look Around Hinesburg and Charlotte, Vermont” by Lilian Baker Carlisle, Chittenden County Historical Society, 1973.

Throughout the building are various items donated by local families over the years that reflect daily life in the town. There’s an old iron stove including an early humidifying vessel. A grandfather clock. A photograph of the members of the Masonic Temple. Cole points out examples of fine handwork, including crocheted lace, needlework and fine embroidery done by local residents.

The museum’s collection has already outgrown its modest space. Cole pulls back a curtain in the back of the museum to reveal teetering stacks of items, including the entire print archives of The Charlotte News and decades of the town’s business ledgers. (A neatly handwritten entry from 1956 shows that Theodora Meader was the town’s highest paid teacher with an annual salary of $261.93.)

“The Museum shows that Charlotte has had a rich and interesting life,” says Society member Molly King (who traces her family to local resident Wilson Williams, one of the townspeople noted for firing a musket from the Charlotte shoreline at British troops in the War of 1812). With the collection of items from everyday life in Charlotte, “you get to see how people really lived,” says King. “It gives you a different way of seeing. It’s fascinating.”

A mid-19th Century sleigh sits in a corner, a two-passenger “cutter” complete with sleigh bells and a small footwarmer that was filled with charcoal from a stove. “I love that sleigh,” says King. “I like to think what it must have been like to travel that way with skirts down to your ankles, bundled up against the cold, with your feet warm and the sleigh bells ringing.”

The Charlotte Museum will re-open post-pandemic and plans to welcome in-person visitors on Sundays from 1:00 to 4:00 p.m. starting in July and August. For more information contact Dan Cole.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]