“White Fragility” moves the glacier

Hello, reading friends. I hope this finds you healthy, happy, and staying more or less sane in what I hope are the days of a waning pandemic. I hope you have been able to enjoy some outdoor time in the recent beautiful weather we have been having. Yesterday was extraordinary, with white snow, sparkling sunlight, glittering ice floes breaking and clattering in the bay, a brilliant sky. My friend and I spotted two Canadian geese and what we thought was a little flock of fuzzy-looking  goslings exploring the perimeter of the lake—is that possible? It felt almost…dare I say…springlike.

goslings exploring the perimeter of the lake—is that possible? It felt almost…dare I say…springlike.

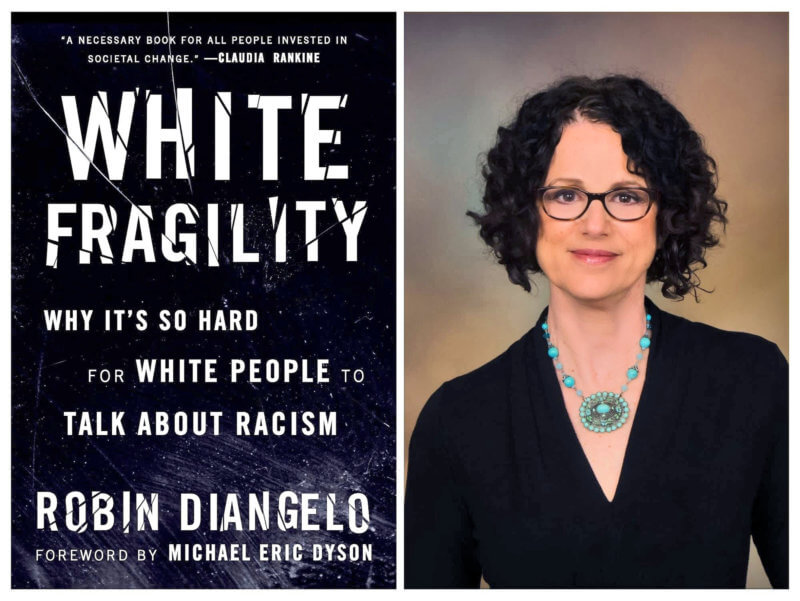

I have to say before I go any further that if you have read “White Fragility” by Robin Diangelo, and I know many of you have, I would highly recommend reading it again and meeting with others to discuss. You may have already done all this, but Sunday afternoon, hours after a Zoom group discussion of this book, I found myself feeling an almost physical, mental/visual shift of consciousness. It is hard to describe; it was kind of like my mind was a glacier and it moved. It didn’t move a lot, maybe it moved just a little, but a glacier is huge and so any small movement is kind of seismic, right?

The chapters describing some of the responses of white people in workshops led or co-led by the author were especially illuminating about how white fragility has a way of holding back the process of understanding racism by diverting the focus back to white people’s discomfort and pain. The chapter on white women’s tears also really got me thinking, pondering, and reflecting.

“White tears,” Diangelo writes, “refer to all the ways, both literally and metaphorically, that white fragility manifests itself through white people’s laments about how hard racism is on us.” “White women’s tears in cross-racial interactions are problematic for several reasons,” she goes on. One is that our tears trigger the terrorism embedded in the history of black men being tortured and murdered because of a white woman’s distress. “When a white woman cries, a black man gets hurt,” Diangelo’s African American colleagues often say—a warning based on devastating examples such as that of Emmet Till. He was a 14-year-old boy who, in 1955, was accused of flirting with a white woman in a Mississippi grocery store. The woman, Carolyn Bryant, reported the flirtation to her husband, Roy, and a few days later, Roy and his half-brother abducted Till from his great-uncle’s home, beat him to death, mutilated his body, and sank him in the Tallahatchie River. The perpetrators (who later admitted to the murder) were acquitted in an all-white jury. In 2007 Carolyn Bryant admitted that she had lied and recanted her story about Emmet Till and the grocery store.

There is a history to white women’s tears, a history that is devastating to the black community. “Not knowing or being sensitive to this history is another example of white centrality, individualism, and lack of humility,” says Diangelo, who goes on to explain that there are various reasons white women cry in cross-racial interactions. One is that sometimes we are given feedback on our reactions and the feedback hurts our feelings. Diangelo gives a good example of how a white woman’s tears can totally detract and deflect from the issue at hand. In a workshop Diangelo co-led, a white woman attendee attempted to rephrase what a black man had just said.

When the black co-facilitator pointed out to the white woman that she had just reinforced the racist idea that she could speak for a black man, the woman burst into tears. “The training came to a complete halt as most of the room rushed to comfort her and angrily accuse the black facilitator of unfairness. (Even though the participants were there to learn how racism works, how dare the facilitator point out an example of how racism works!) Meanwhile, the black man she had spoken for was left alone to watch her receive comfort,” writes Diangelo, “Whether intended or not, when a white woman cries over some aspect of racism, all the attention immediately goes to her, demanding time, energy, and attention from everyone in the room when they should be focused on ameliorating racism. While she is given attention, the people of color are yet again abandoned and/or blamed.”

You may have noticed how the question almost always inevitably arises from discussions on racism, What can we do as white people to make things better? It’s a good question, a practical question. Diangelo says that she herself strives to be “less white.” “To be less white is to be less racially oppressive. This requires me to be more racially aware, to be better educated about racism, and to continually challenge racial certitude and arrogance. To be less white is to be open to, interested in, and compassionate toward the racial realities of people of color. … To be less white is to break with white silence and white solidarity, to stop privileging the comfort to white people over the pain of racism for people of color, to move past guilt and into action.”

This book is mind-opening, spirit-opening, history-opening, and assumption-opening. I will not be the same as I was before reading it, nor will I see the world and society in the same way I did before. So thank you, Robin Diangelo. I think it is a good thing for a white person to learn what white fragility is, how it develops, how it protects racial inequality and systemic racism, and what white people might do to make things better now.