A resistance fighter in Auschwitz, and lessons for our time

The story is thrilling: a Polish man voluntarily goes to Auschwitz, and forms an underground resistance within the confines of the concentration camp, then makes a daring escape. On one level, Charlotter Jack Fairweather’s new book “The Volunteer” is an exciting nonfiction account of a little-known World War II hero who risked everything to let the world know of the atrocities taking place behind the camp’s walls. On another level, it is a stark reminder of what happens when a government turns on its people and turns them against each other, and at the same time is an affirmation of the power of a single individual even when hope seems to be a dying light.

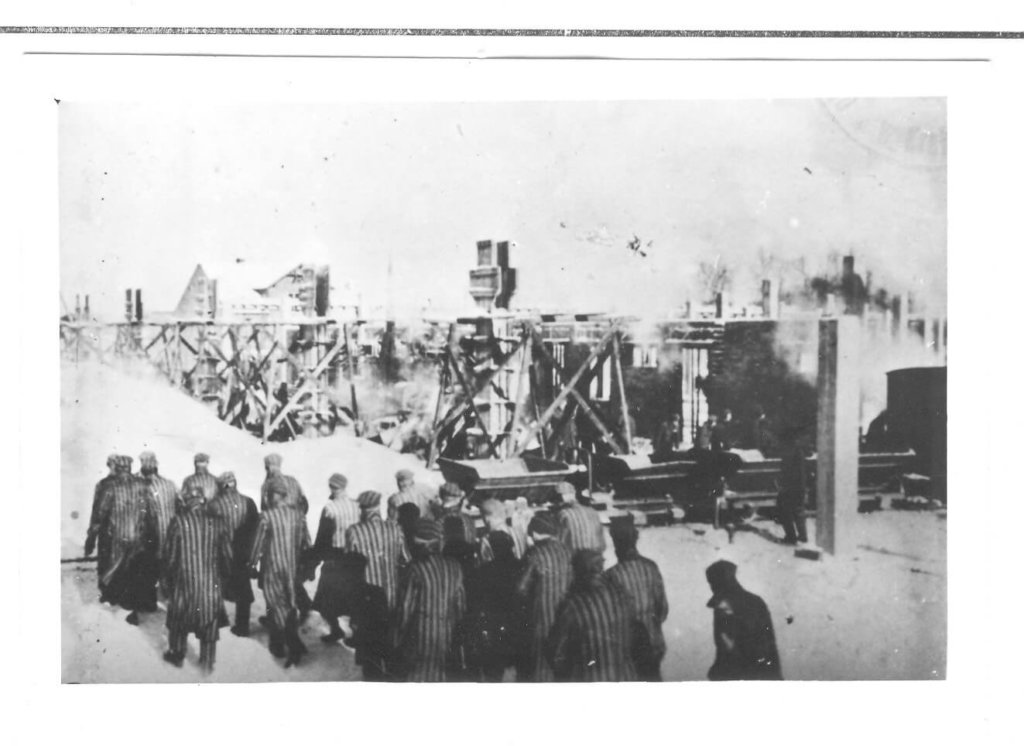

Witold Pilecki volunteered to be brought to Auschwitz as part of a resistance effort to report to Allied forces in WWII the atrocities going on at the concentration camps. Within the walls of the concentration camp, he found trusted confidants through whom he was able to secretly convey information to people on the outside.

Fairweather is a reporter who has been embedded in Iraq and Afghanistan, and said his interest in Pilecki grew after a conversation with a colleague after a war assignment who had seen a small exhibit on him at Auschwitz.

“I remember being blown away by this idea,” he said. “There were guys in Auschwitz who were assassinating SS officers, stealing radios to broadcast messages, sabotaging facilities, copying and smuggling out records, and it gave me just this whole new perspective on the camp.”

Pilecki’s story wasn’t known until the 1990s; after he eventually escaped from Auschwitz—yes, that’s something that actually happened—he fought against the communists in Poland and was eventually captured and executed. Fairweather said his story was buried for a long time afterward. “His wartime records were hidden or destroyed, those who fought with him faced arrest if they talked about him, his family was declared enemies of the state, and had a very rough and brutal time of it.”

He said that after thinking for decades that Pilecki was a traitor, when the documents were finally released, “They had an amazing moment when they received one of his reports from the camp, and they realized his spectacular achievement.”

The presence of hope, and the ability to trust others even in the face of unimaginable atrocities perpetrated by fellow men, was the key to Pilecki’s survival. Fairweather said that strength of character was what appealed to him the most about Pileck’s story. “His life was threatened in so many ways, so many times; it was truly a deadly place to be, but somehow he kept to his moral compass and had the strength to inspire others with his vision,” he said. “As a kid you have this Holocaust education, and you understand that it’s this place of unbelievable suffering and evil… What I found from Pilecki’s story is this perspective of a protagonist within the camp. It’s really energizing when you realize that even in a place like Auschwitz, it’s possible to resist.”

With a team of five researchers, two of whom spent two years reading through archives of material at Auschwitz, Fairweather was able to piece together Pilecki’s activities within the camp, as well as his eventual physical escape. He even went to the concentration camp and left to follow the exact escape route, leaving at 2 a.m. just as Pilecki did.

With the passage of time and the softening of history’s lessons over decades, Fairweather said that it was important to him to capture the strength and spirit of Pilecki and his heroism in a way that is relevant to people now. “In some ways it’s hard to really enter into that story from our perspective 80 years later…and that’s our duty as the second and third generation, to never forget,” he said.

The surviving witnesses who spoke with Fairweather were children when they met Pilecki; he recalls speaking with one who was with Pilecki in the moments before he was captured and brought to Auschwitz. Even as an old man, the witness remembered dropping his teddy bear, and Pilecki calmly picking up the toy and handing it back to him.

Fairweather said there were specific, tangible qualities about Pilecki that led him to accomplish what he did—ironically, at a time when he should have had his lowest opinion of humanity and a distrust that people were capable of doing good, he was able to trust.

A one-page document was discovered that Pilecki wrote before his death. It reflected on the lessons he had learned through his life so far, Fairweather said, and one thing that stood out was the lesson Pilecki learned from his experiences in the camp.

“His conclusion was that he wasn’t sure how to understand what happened, only that his memories of speaking with people and being with them right before they died was that they wished they had been connected to, or closer with their loved ones,” he said.

Fairweather said professional and personal growth of his own has come from being so close to Pilecki over the past three-plus years of research and writing.

“Pilecki’s story made me realize what a privileged position I’d been in reporting from Iraq and Afghanistan,” he said. “My objectivity as a journalist was partly based on the fact that I could walk away, but Pilecki didn’t have that luxury. He had to nurture a deeper set of values to report on the suffering around him…I was constantly amazed by how much living history still exists to connects us to the past and how much we can still learn from that amazing generation.”