Local heroes

Driving by the Charlotte Town Beach I noticed a little ice forming on the edge of Lake Champlain on this calm, cold January day. I wondered if the lake would freeze over this year. My mind wandered back to February 22, 1988, when the headlines of the Burlington Free Press screamed, “Ice Fishermen Saved, 23 snatched by helicopter from drifting ice on lake.” I came home and pulled out from my files a story that I had written that summer based on an interview with Fred Wedge, an ice fisherman on that ice floe and an East Charlotte resident. I think his harrowing story is important to share, both as a warning and as an inspiration.

Driving by the Charlotte Town Beach I noticed a little ice forming on the edge of Lake Champlain on this calm, cold January day. I wondered if the lake would freeze over this year. My mind wandered back to February 22, 1988, when the headlines of the Burlington Free Press screamed, “Ice Fishermen Saved, 23 snatched by helicopter from drifting ice on lake.” I came home and pulled out from my files a story that I had written that summer based on an interview with Fred Wedge, an ice fisherman on that ice floe and an East Charlotte resident. I think his harrowing story is important to share, both as a warning and as an inspiration.

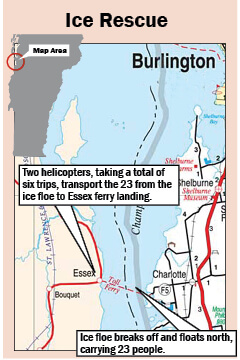

I titled this story, “Local Hero,” and I certainly saw Fred as a hero in this story. Then I started thinking about the 23 other people who had come to ice fish off of the north shore of Thompson’s Point. The Point sheltered the fishermen from the 35-knot winds blowing from the south. Though mostly men, there were two women and four children as well. All of these people had to have a spot of heroism to be able to work together, think out their next steps and help each other survive in the face of death.

Fred Wedge, 62, begins his story by telling me that he was fishing with his buddy, Cramer Humphrey, who was celebrating his 45th birthday with his brother Joe. They were in their shanty, a jig stick in each hand, pulling smelt out of the 6-inch deep hole in the ice. The fish were biting so good that they didn’t have time to walk to their truck to get a beer.

Around 11:30 in the morning, Humphrey says, “Your line is in my hole. Just saw the flasher go by,” and Fred responds, “You’re crazy, I put my line in straight down.” Then they all heard a loud snap and got out of their shanty to see the shoreline 100, 200 yards away, and they were moving fast with black water opening up. They heard a woman nearby yell out, “You got your bathing suit with you? You’re going to need it.”

A lot of thoughts went through Fred’s mind. He was a good swimmer, but Cramer and his brother didn’t swim at all. He knew that Garden Island would come up soon with the wind blowing them north and maybe they would get jammed up next to the island and they could get off. They just slid by the island, however, with water in between. Then they were in the main lake with the wind blowing like hell and 5-foot waves. Fred figured that there were 30 or 40 acres of ice and that maybe the ice was attached to the New York shore.

There was no one leader, but they decided together to start walking on the expanse of ice that seemed to stretch to the New York shore. One person had a shanty that collapsed into a sled, and they pulled some of the children on the sled. Everyone was leaning against the wind, but those people who did not have crampons on were struggling to get good footing. People helped each other on the slick ice, and Cramer and Fred carried their 5-gallon buckets of smelt and their ice augers as well. Fred estimated that they walked 4 or 5 miles with no one talking much. He reported, “Humphrey, he usually smokes one cigarette after the other, but I didn’t see him light up a one.”

When they finally reached close enough to see the New York side they saw that there were at least 300 feet of open water between them and the land. They gloomily turned around and started walking back on their island of ice toward the Vermont side. Had anyone seen them? The ice was getting chewed up by the wind and the waves. Suddenly, as the group was clutched by fatigue and fear, a plane appeared and circled their ice. Fred recounted, “Some of us waved our arms. Joe, he was a Vietnam War veteran. He got busy organizing everyone to lie out on the ice and make the letters SOS with their bodies. I was damned if I was going to lie out there. The ice was only 6 inches thick. Get all that weight in one place and you’re asking for trouble. Besides, the plane would have a radio to call for help. The problem was how much time this here piece of ice would stay together. I don’t mind so much for me, but there was them kids to think about.”

Fred and the others were getting close to the Vermont side. He and Humphrey were talking about cleaning out their shanty. “No sense losing good equipment if you don’t have to,” explained Fred. Then another fellow said that he had a good long piece of rope, maybe a hundred feet or so. That got Fred musing. They were coming up fast on Sloop Island. Fred thought to himself, “I’m a good swimmer, swim all the time. Maybe we could tie a rope to my waist if we passed close enough to Sloop. I could jump, swim the last bit, may be get some of those kids off with a rope.”

When they got up near the shore of tiny Sloop Island, however, there was too much open water, and it was barricaded with big chunks of jagged ice.

They all started walking to the center of their piece of ice. As the ice was breaking up the shanties were just dropping out of sight one, two, three, maybe 100. Fred lost his shanty, just watched it go. There wasn’t much ice left, about an acre, and the sheet of ice was undulating with the waves. Fred told the end of the story saying, “It was Joe who spotted the ‘copter. I couldn’t see a damn thing, but he was a Vietnam Veteran you know. He started waving. We all decided the women and children would go first. Pretty soon we spotted a second ‘copter. We waited, lined up in the middle of that ice. Humphrey and me, we said that we’d go last, hoped to get our fish and equipment aboard. Joe says if he ever gets off this ice, he’s never going to get back on it again. He says Vietnam mortar fire is safer.” Fred described the helicopter coming down, weaving, blades beating the wind. The kids clambered right up the runners and were pulled aboard. It was a Vermont Army National Guard helicopter with room for seven. The women got aboard too. The New York police landed their ‘copter next. They had room for four. In total the National Guard would make three trips, and the N.Y. State police landed twice in spite of the pilots’ fear of getting laid over by the wind or the ice breaking up with the weight of the helicopters.

The rescue crew had drilled a hole to measure the thickness of the ice. It was now only 2 inches thick.

Fred and Humphrey were the last to be picked up at 2:40 p.m. with their two pails of fish, the augers, chisel, sticks and the stove. Fred ended his story saying, “One of the ‘copters radioed in to us that 15 minutes after we were rescued the rest of the ice broke up and was blown to nothing. It was a hell of a wind and we had been floating on that ice for three hours.”

I would like to think that each of us would have a bit of heroism in us if we found ourselves facing possible death. Thoughts and actions like helping each other, working together, being brave, putting children first, dreaming of heroic action even when opportunity does not present itself—all these attributes came out in the courage that was shown by the rescuers and the survivors. For me this is community at its best.