There’s more to your core

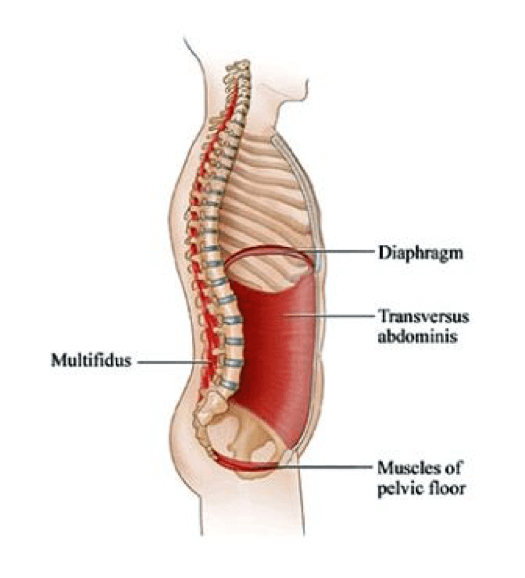

When you stop and consider your core, what is the first thing that comes to mind? If you are like most people you probably thought of your belly and abdominal muscles. Popular culture tends to emphasize the chiseled “six pack” as its crowning definition, but this is just one piece of a greater whole. The core actually involves a number of other lesser-known muscles that create a three-dimensional oval-shaped container of support for the center of your body. By taking a more in depth look at these other areas, you can learn how to use the whole core to support your daily movements.

When you stop and consider your core, what is the first thing that comes to mind? If you are like most people you probably thought of your belly and abdominal muscles. Popular culture tends to emphasize the chiseled “six pack” as its crowning definition, but this is just one piece of a greater whole. The core actually involves a number of other lesser-known muscles that create a three-dimensional oval-shaped container of support for the center of your body. By taking a more in depth look at these other areas, you can learn how to use the whole core to support your daily movements.

At the bottom of the oval lies an important and often overlooked group of muscles collectively known as the pelvic floor. They create a hammock-shaped band of muscles at the base of the pelvis, and their main function is to support the pelvic organs as well as to prevent the flow of urine or the passage of a bowel movement. You may be familiar with the “Kegel” exercise, a well-known exercise technique used to prevent urinary and fecal incontinence. To identify this area, try to tighten the muscles you use to keep from passing gas or urinating. You can learn more about the Kegel exercise by visiting the National Association for Continence website.

Most people are surprised to learn that the gluteal muscles, a set of three individual muscles in the back and side portion of your hips, are also a part of your core. They are thick and powerful muscles that connect your pelvis to your femurs (thigh bones), enabling them to move and support your hip joint. The gluteals play a critical role in safely translating the weight of your trunk into your hips and lower body. If you are unsure how to feel these muscles, try standing on one leg and attempt to squeeze the buttock on that same side leg. If done correctly, you will recruit both the back and side portions of this muscle group.

Running up and down each side of the spine are a group of muscles that keep the spine erect, also known as the “anti-slouching” muscles. As a group they are known as the erector spinae, but they involve a number of different individual muscles that support and move your spine. Try sitting in a chair and alternate between slouching and sitting tall. While in an upright posture your erector spinae are working.

Running up and down each side of the spine are a group of muscles that keep the spine erect, also known as the “anti-slouching” muscles. As a group they are known as the erector spinae, but they involve a number of different individual muscles that support and move your spine. Try sitting in a chair and alternate between slouching and sitting tall. While in an upright posture your erector spinae are working.

In the rooftop section of the core we find a single muscle called the diaphragm. It lies just below the lungs and is shaped like a big three-dimensional dome. The diaphragm plays a vital role in respiration. When it contracts it presses downward towards the abdominal cavity, creating space for our lungs to expand and trigger inspiration. To assist exhalation, the diaphragm relaxes back up into its original parachute position, helping the lungs deflate.

Most of us use our diaphragm without having to think about it, but sometimes we develop a breathing pattern known as “chest breathing,” which neglects the diaphragm. Try taking a few breaths and notice if your chest and belly expand as you breathe in. If your chest balloons but your belly remains still then you are not using your diaphragm as well as you could. To strengthen your diaphragm and promote a healthier breathing pattern, practice moving your belly outward as you breathe in and letting it relax as you breathe out. This technique is known as diaphragmatic or belly breathing and will not only improve your lung capacity but has also been shown to have a positive effect on blood pressure and stress.

The last muscle group is, of course, the abdominals, which are actually four different muscles spanning the front, sides and portions of the back part of your torso. The abdominals work together to help you side bend, rotate and flex your torso, but they also play an important role in breathing and supporting your internal organs. Take a deep breath in and then quickly and forcefully breathe back out. During the forceful expiration try to sense the muscles in your belly and side of your torso engaging. When you feel like you have a handle on this, attempt to engage the abdominals without forcefully exhaling.

The last muscle group is, of course, the abdominals, which are actually four different muscles spanning the front, sides and portions of the back part of your torso. The abdominals work together to help you side bend, rotate and flex your torso, but they also play an important role in breathing and supporting your internal organs. Take a deep breath in and then quickly and forcefully breathe back out. During the forceful expiration try to sense the muscles in your belly and side of your torso engaging. When you feel like you have a handle on this, attempt to engage the abdominals without forcefully exhaling.

The following is an exercise to help you use the above information and start to become more conscious of your oval core. Lay on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the floor. Place an item between your knees such as a soccer ball or folded blanket. Place your hands on your belly, breathe in and try to feel your belly rise upward. As you breathe out, squeeze your naval down towards the floor, squeeze your thighs around the object between your knees and attempt to lift your buttocks up from the floor a few inches. Slowly lower back down and repeat this sequence 10 times.

With practice you will improve your awareness of the whole core used in this one exercise. The next step is learning how to use these muscles during your everyday movements. Lifting a suitcase, standing up from a chair or reaching a heavy plate up onto a high shelf are examples of movements that you can challenge yourself to engage your core while performing. There are a myriad number of beneficial exercise programs to help your core get stronger, but crafting a mindful approach is an important place to start. After all, a strong core should not be something designated for the gym alone. A healthy and whole core is one that is an integrated part of your daily life.

Laurel Lakey is a physical therapist assistant at Dee Physical Therapy in Shelburne and lives in Charlotte with her husband, dog, chickens and sheep. You can contact her with comments or questions by email.