Curbing Our Way Across America

In the age of innocence

Prologue

1964 was a pivotal moment in our nation’s history. It’s a year the Boomer Generation will remember well. But for those who arrived later I hope it provides a glimpse into an America of incredible idealism and social turmoil on a collision course. It’s history. Speaking for myself, it’s what shaped the world I live in today.

This is a memoir about the summer of 1964 (not the turbulent emerging 1967) as seen and experienced through the lenses of two naïve idealistic college kids who grew up comfortably in the Midwest and spent the summer touring and working in suburbs of the South and West. It is a very thin personal slice of the larger America that evaded us.

Preface

Des Moines, Iowa. May, 1964.

“The times they are a-changin”

~ Bob Dylan, 1963

“When the truth is found

To be lies

And all the joy

Within you dies”

~ Grace Slick, Jefferson Airplane, “Somebody to Love,” 1966.

Grace wailed this anthem that ushered in the turbulent late sixties several years later but the anger was simmering that summer. Many youth felt they’d been betrayed and lied to by the adults who ran the “system.” They had no voice. They felt powerless.

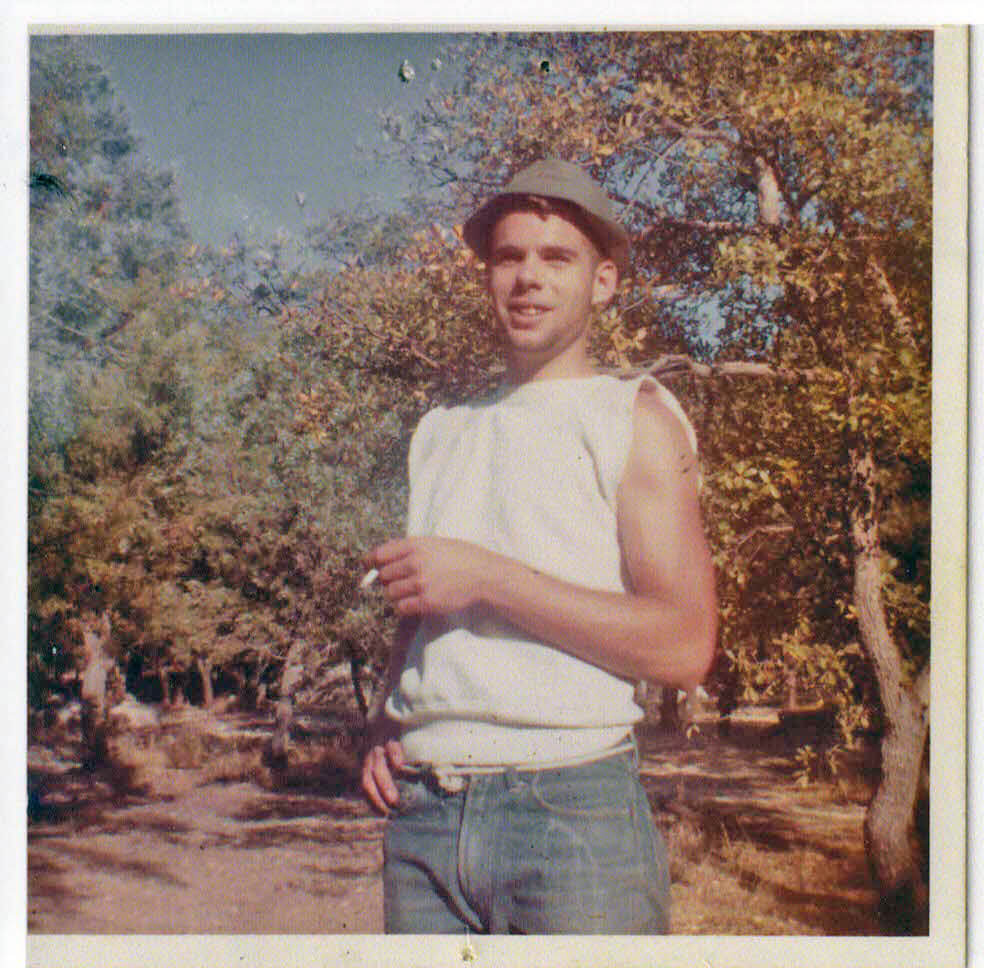

As Mark Thompson and I embarked on our bold adventure in suburban America in 1964 we were only remotely aware of the rumblings. We were intoxicated by the prospect of a just and prosperous future. (John Lennon’s “Imagine”). Our insulated comfortable Midwestern upbringing pointed to a life of unlimited possibilities. We were naïve liberal activists, optimists buoyed by folk music and the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. What I’d now give to again be swept up by the euphoria of that era, if only for a fleeting moment, to be able to recapture and savor the fervent spirit of idealism pointing to a utopian world.

Unbeknownst to us a social and political tsunami was welling up and poised to strike. There were several giant divergent waves looming on the horizon and they were surging in radically different directions. We were vaguely aware of them but they seemed distant and removed. Some held great promise and some were ominous, but the bad ones could be conquered.

For thirteen days hair-raising days in October, 1962, Cold War tension between the United States and its superpower arch enemy the Soviet Union teetered on the brink of a full scale nuclear war. The Soviet Union had deployed nuclear missiles to Cuba, prompting President Kennedy to set up a naval blockade against a Soviet fleet steaming toward Cuba. Both Kennedy and Premier Nikita Khrushchev realized the crisis had to be resolved to avert a catastrophic world war and negotiated a last-minute deal: Kennedy agreed to remove missiles the United States had previously deployed in Turkey and promised not to invade Cuba, and Khrushchev in turn agreed to remove the Soviet missiles from Cuba. The fleet turned back.

President Kennedy had been assassinated in 1963 and with his murder the chalice of Camelot had been smashed. But because this was the first presidential assassination since William McKinley in 1901 it was seen as an isolated tragedy in the eyes of most.

The civil rights movement had just exploded onto the national scene. In August of 1963 The Great March on Washington was held in Washington, D.C., with over a quarter of a million marchers advocating for civil and economic rights for black Americans. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. stood in front of the Lincoln Memorial and delivered his historic “I Have a Dream” speech. In 1964 Congress narrowly passed the Civil Rights Act, one of the most important pieces of legislation of the twentieth century. It ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex and national origin. It was ferociously opposed by conservative Republicans and southern states, but President Johnson masterfully pushed it through.

South Vietnam, an obscure country in Southeast Asia, was hardly on the public’s radar and had yet to rear its cobra head, but that all changed in the summer of 1964 when Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, authorizing President Johnson to “take all necessary measures, including the use of armed force” against any aggressor in the conflict. The United States was concerned that South Vietnam would fall to communist North Vietnam and become a Russian and Chinese satellite, causing a “domino effect” that would engulf all of Southeast Asia. By 1965 able-bodied males were being drafted and a college uprising was ignited by what many considered an immoral war.

The Free Speech Movement began at the University of California Berkley in 1964 as a protest against the university ban on on-campus political activities. It sparked an unprecedented wave of student activism and involvement. Authorities responded violently, unleashing the police and military to quell the protests. Six years later four students were shot and killed at Kent State University by a National Guard regiment during a peaceful protest.

Rachael Carson’s1962 book Silent Spring, pointing out the dangers of applying chemicals to the environment, was a blip until 1964 when it hit mainstream media. The pesticide industry went after her with a vengeance but the environmental movement’s fire had been lit.

The African American inner cities were a powder keg ready to explode. White America nervously sensed it but chose to turn a blind eye to the “ghetto/negro problem.” Several years hence the Black Power Movement and urban riots sent white America reeling in paranoid convulsions.

Republican Barry Goldwater ran against Democratic incumbent Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and was clobbered because he was labeled an “extremist.” By today’s measure he would be called a moderate.

Despite our unbridled optimism we would soon come to realize how oblivious and out of sync suburban America was to these gathering changes. 1964 was a watershed year, a turning point from which the nation could never turn back.

Times have changed. Really changed. In 1964 I embarked on an adventure that would today result in a trip to the hospital if not the morgue. This is a true tale of my escape from despair into a meandering saga that played out beyond my wildest dreams.

Despair

Bracing for the summer of 1964 I’d hit bottom. I’d finished the second semester of my sophomore college year in a slump funk: jilted in love, too much partying, a precipitous slide in grades and the looming prospect of another year with a summer job straight from a frozen Dante’s Inferno. There did not appear to be any viable escape route, so I resigned myself to enduring the inevitable grim reality.

The previous summer I’d worked as an ice cream stacker for Beatrice Foods under the brand name Meadow Gold. My job was to take ice cream cartons off a chattering conveyer belt in The Box, a -20 degree Fahrenheit gloomy cavernous room. I would stack the cartons on racks where they would harden from slush to granite.

After parking my car and walking through the sultry summer air I’d punch a clock and enter the dressing room where I’d change into insulated boots and layered thermal underclothing encased in a parka. The Box was brutally unforgiving: Dark and forbidding with eerie mists wafting and drifting about as if in a polar medieval dungeon.

The onslaught of cartons marching off the assembly line was as relentless as the brooms carrying endless buckets of water to Mickey Mouse as the sorcerer’s apprentice in Walt Disney’s Fantasia. Occasionally I would fall behind and hear the dreaded splat of ice cream hitting the floor. Then Dutch, the most irascible tormenting boss on the planet, would appear on the scene. Dutch was hard-fisted blue collar to the core and held a seething grudge against west-side college kids. He would launch into a screaming profanity-laced tirade and order the line shut down while I scraped the goo off the floor. He was borderline legally blind, and I took some consolation in grinning as I flipped him the bird through a veil of fog.

There were other mortifying aspects to the job. While my friends sported sun tans, my face, being exposed to the bitter cold eight hours a day, was ruddy with frostbite. My nose glowed red, leading to my adopted nickname “Rudolph.” And twice a day I had to slide the frozen racks on a manual forklift and haul them out to the semi-trucks. The trucks pulled into the loading docks from Ingersoll Avenue, one of the busiest streets in Des Moines and were clearly visible from the street. It was a traffic stopper for people who drove by to see me wearing a parka in scorching July heat. Once a carload of greasers – sixties duck-tailed hoodlums from the other side of town – slammed on the brakes and stared at me incredulously. One of the guys pointed and yelled, “Look, it’s Sergeant Preston!” (Sergeant Preston of the Yukon was a popular TV series of the late fifties starring Dick Simmons as an intrepid Canadian Mountie who, accompanied by his horse Rex and faithful dog Yukon King, battled the harsh arctic elements to bring criminals to justice.)

All this for $1.65 an hour.

Hope

Mark Thompson listened with feigned sympathy as I lamented my fate over a beer at Peggy’s, the local pub near the Drake University campus. Empathy was not one of his strong suits. We were in the same fraternity but only casual friends, and meeting that evening was happenstance.

Mark possessed some quirks that would irritate a Labrador retriever. While a great guy at heart he was stubborn as a mule and had this annoying habit of constantly telling jokes, staring at the listener and, if there was any hesitated reaction, lapsing into animated laughter. He would always precede his jokes with a patented Cheshire cat grin which, for those who knew him, set the stage for a pokerfaced reaction. But this never seemed to faze him; he reveled in telling the joke. He was a swashbuckling entrepreneur in the purest sense, a guy who could never take orders and always had a better way of doing things. But to his credit he always had a scheme for making money and landing on his feet. And he had a driving work ethic. The previous summer he bought an old school bus and recruited four friends to ramble their way out to California where they picked fruit alongside migrant workers. Despite frequent bickering there were no altercations, and they returned intact as friends.

After I’d bemoaned my fate Mark squinted, cocked his head, and stroked his forefinger on his chin. “Did you hear about Bob Peterson’s older brother”? “No,” I said. “Well, he’s a member of the Rockford, Illinois Jaycees. Bob told me that as a fundraiser they made a load of money painting house numbers on curbs and collecting donations.” I perked up.

Mark went on. “I’m thinking … why couldn’t we do the same thing? We could do this in Des Moines and collect donations as enterprising college students trying to pay for our education. People would love it.” And so the idea was hatched.

I had reservations about launching into any joint endeavor with Mark but considered giving it a gander. He was not one to be deterred by obstacles or, for that matter, reality and was willing to take the plunge if I agreed to join him. Being by nature cautious I began to think about the downside of such a venture, bottom line being, what if we failed? Like most fervent entrepreneurs, he wouldn’t entertain a negative side of any idea and predictably threw caution to the wind. He asked me the ultimate question: “What have we got to lose?”

A fleeting image of Dutch slinked across my mind. I was in.

Mark called Peterson’s brother who laid out the details of the Rockford project. The Jaycees put articles in the Rockford Register Star touting the laurels of their fundraiser and followed up with fliers in neighborhoods listing a phone number to call for a donation. There was no set price but most people donated fifty cents and a few a dollar – a hefty return back in ’64.

We were off and running.

Stubbornness spawns all invention

Plato wrote that necessity is the mother of all invention. Mark wouldn’t quarrel with that maxim but would carry it one step further. Bullheadedness and perseverance had always propelled him through life. I think he always regretted that Henry Ford beat him to the punch.

The mechanics of painting curbs was still vague, and I argued that we should research how previous entrepreneurs pulled it off. Why reinvent the wheel? Mark wouldn’t hear of that. I held my ground and did a little research at the library but couldn’t find much; apparently curb painting was an undefined profession. So I begrudgingly handed him the reins.

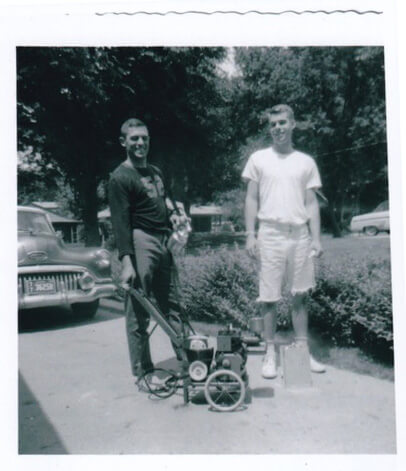

The first challenge was how to apply the paint. We heard from Bob that the Rockford Jaycees used aerosol cans to spray white paint over a rectangle followed by black paint over the interlocking metal stencils. Marv argued that we’d save considerable money if we used a compressor to apply the white paint. So we invested in a paint compressor and mounted it on a Red Ryder wagon powered by a small Briggs and Stratton engine. His contraption was a sight to behold. It would shimmy, lurch, and hiss so we dubbed it Stanley Steamer.

We also had to come up with a way to carry our supplies and access the interlocking number 1-10 stencils. Our solution was the curoborator, a large wicker basket with a Styrofoam slab that covered the top of the basket. We positioned and inserted tongue depressors to align and hold the respective interlocking stencil numbers. Supplies were stored inside the basket, including gloves to protect our hands while painting, water bottles, snacks and a transistor radio.

The lead person used Stanley to spray fast-drying matted white paint on the curb over an 8-inch by 18-inch rectangle cut out of a larger piece of cardboard. The trailing person then sprayed glossy black paint over the stencils.

We did a dry run on Mark’s block in Des Moines to test how our procedure worked. Stanley was a comical traffic stopper. Drivers would slow down and cock their bemused heads, and before long a crowd of little kids gathered around jumping and pointing in convulsive laughter.

Predictably, there were some bugs to work out. The biggest problem was that about every half hour the nozzle hole would clog up, and we’d have to insert a skinny screwdriver to free it up. Also, as the black paint accumulated it initially turned from sticky goo to a hard thick shell that was almost impossible to remove. Again, Mark’s ingenuity to the rescue. He experimented with black lacquer gloss paint, and to our great relief we discovered we could easily peel the paint off after it dried. The cardboard wasn’t a problem because when the white paint accumulated it could easily be replaced. We wore cheap cotton work gloves to protect our hands. They would quickly become gummed up, so we purchased replacement gloves in bulk.

Down but not out

Step one was to gain permission from the Des Moines City Council. How could they turn down such a heartwarming beneficial service from enterprising college boys? We reserved a spot on the docket, donned our suits, and made our appeal.

The council’s initial reaction was one of patronizing praise. But after a few minutes some members squinted and cast sideline glances at one another. As the discussion progressed doubts began to surface. Some people might not be happy having college kids solicit them for donations. Were there liability issues? Was such a project legal under city ordinances? They queried the public works director, who stammered and said he’d have to look into it. The mayor picked up on the vibes and tabled the discussion. The council patted us on our heads and kindly showed us the door.

Lesson number one learned: Never go to an elected political body and expect a timely decisive answer.

Soldiering on

We didn’t tuck our tails for long. There were suburban pastures in the metropolitan area to be tapped, and from now on we wouldn’t make the mistake of asking permission from city government.

We designed and printed a flier promoting our enterprise that would be slipped in the front screen door of every house. We planned to revisit those households the next evening and jot down the addresses of those who wanted to have their curbs painted and accept donations. The flier read:

As a service to you and your community

You Have an Opportunity to Have Your House Number

Newly Painted on Your Curb

Besides Being Clearly Visible During the Daytime

If at Night …

The Doctor or Ambulance

A Delivery boy or Taxicab

Out-of-town Guests

The Firemen or Police

Seek your home, they will find your house number

QUICKLY AND EASILY WITH NO MISTAKE

This service is being sponsored throughout the community by college students who help earn their school expenses this way. There is no charge for this service. However, contributions will be accepted.

We think this project is a benefit to everyone – don’t you? Please save a donation or smile for the college student who will be stopping by in the next few days to ask if you are interested in participating in this community safety program.

THANK YOU

THE COLLEGE STUDENTS

While we struck out asking permission in the City of Des Moines we decided to give it another shot in Windsor Heights, my west-side suburban hometown. At the time Windsor Heights was the most well-healed suburb in the metro area, graced with late 1950s/early ‘60s brick ranch homes that conjured up visions of Hollywood with streets like Sunset Terrace, Bryn Mawr Drive, Bellaire Avenue, El Rancho Drive and Marilyn Circle. I was a known quantity there, and the mayor and several council members knew and liked me. So again we dressed up and gave our pitch to the city council. They embraced us warmly and gave their stamp of approval. We gained credibility with an article in the weekly newspaper, the Windsor Heights Times. We left the council chambers in a euphoric state ready to excavate a veritable gold mine in waiting.

The day of reckoning was now upon us. Early the first afternoon we jogged across lawns in a six-block area leaving slips in screen doors. This was 1964 and most women were homemakers tending their children during the day. If they saw us and opened the door we would hand them a flier and explain our project. Most were intrigued and supportive but not ready to give a donation until they could consult their husbands when they returned home from work. A few, however, offered to donate on the spot. We thanked them and jotted down their addresses in our notebook, explaining that we would be returning within several days to paint their curbs. After completing our rounds we retired to Peggy’s for beer and pizza.

We anticipated the possibility of encountering mean dogs and filled our pockets with dog biscuits as a gesture of friendship and appeasement. This worked about half the time, but if there was a standoff the first rule was to stand our ground and stay cool, facing Fido as we slowly backed off into neutral territory. Toy poodles were a major headache. They were the most popular breed of the day, and their incessant yapping would set off every other dog on the block, and sometimes the din would spread throughout the neighborhood. While this was an annoyance, the ones that really scared us were larger dogs that didn’t bark, at least much, but glowered at us with piercing eyes and a murmuring growl. Doberman Pinschers were the most hair-raising of all.

The following evening we returned to the area, knocking on the doors of every household. We started at 6 p.m. when we could count on Ozzie Nelson to have pulled up the driveway and eased into his recliner. Hearing evening news on TV was a sure signal that someone would almost always come to the door.

After calling on a few houses we realized that this approach was going to be a long slog. Many people are by nature curious hagglers. First we had to explain what the painted curb would look like since no curbs on their block had yet to be painted. Our explanation was vague and tedious, and we realized that a photograph would say a thousand words. We took immediate action and always carried a Polaroid print after that first day.

The first two questions most asked were “What do you recommend as a donation?” or “What are most people giving?” Being our first evening we didn’t have a precedent and replied, “Whatever you’d like to give.” One guy reeking of booze told us it was a good idea and to go ahead and paint his curb. We asked what he would like to donate. He swayed and slurred, answering, “Your flier didn’t name a price. It’s a good deal, so I’ll take it for free.” A good number of people wanted to bargain. Our lowest donation was a dime, but most offered fifty cents and a few a dollar.

We finished our first block at twilight, counted the change, and split $21.50. I told Marv I got a better rate of return on my paper route when I was twelve.

Back to the drawing board

We both agreed that our little scheme was indeed little. I told Mark, “I could hear you giving your hard core sales pitch at the houses across the street, and you might just as well have been arguing with the door knob. We can waste a lot of time trying to close a deal on pride that might give us another fifteen cents. You can bleed ‘em out of another dime and win the battle, but at the end of the night you’ve lost the war. I earned $11.80 of our whopping $21.50.”

Mark wasn’t one to give ground graciously, but I had just jabbed his stubborn pride. He countered, “So what now Willy Loman?” (of Death of a Salesman fame.)

I replied, “I don’t know. What do you think?” Mark may have been stubborn, but he was also inventive; whatever the solution it had to be his. “Well … maybe we need to paint first and collect second. We could blitz a neighborhood, leaving our fliers and then come back smiling and look all charming and innocent as the college students. They’d have read the fliers and looked at their curbs so we wouldn’t have to explain.” Eureka!

So the next morning we headed out to Ankeny, a suburb lined with Pete Seeger’s post-war little boxes, and started our blitz. We hired a couple of grade school boys for a penny a house to run up and down the blocks putting fliers in the screen doors. Things were going well until the local cop cruised by and asked us what we were doing. We handed him a flier, which he scrutinized and said, “Looks like a good idea to me. I have a helluva time finding some houses, ‘specially at night. But some guys on the council have been on my case and I don’t need more trouble. I gotta ask you to stop.” We nodded agreeably and sauntered back to our car. “Damn!” I said, “This will never work.” Brazen Marv didn’t see it that way. “Hey, he asked us to quit painting. He didn’t say anything about collecting.” Hmm.

That night we started calling on doors, smiling as clean-cut enterprising college students. The neighborhood was not all that prosperous even by post WWII standards, but most who greeted us were warm salt of the earth folks. Many worked at the John Deere assembly plant there.

By evening’s end we’d collected a whopping $78.50, and my split was more than I cleared in a week at Meadow Gold. Fat City, we’d arrived!

But there was a small problem. We couldn’t continue to paint in Ankeny since we’d been ordered to stop.

Mark had an immediate solution: Move on to another suburb, blitz, collect and move on. But never ever ask for permission from the city in advance.

Guerilla Paintfare

From that day on we became the Viet Cong of curbdom. Strike, fade away and return when the enemy’s guard is down. That became the first and guiding rule of curb painting.

As with any entrepreneurial business venture, you don’t get it totally right the first time. Mistakes and missteps are the best teachers, and by the end of the summer we had graduated cum laude in efficiency, business management, psychology and salesmanship.

As we moved down the street painting we were constantly scanning houses for citizen watchdogs, ever vigilant for peeping heads and fluttering curtains. When a person walked out of the house and approached we would typically be greeted with the question, “What are you doing? Why are you doing this?” To which we would reply, “This is a project throughout your community sponsored by college students to help us earn our school expenses. There’s no charge for this service, but we do accept donations. It will help police, fire, ambulance, friends and out-of-town guests find your house.”

Some folks would offer to pay right then. Others would say, “I didn’t ask you to paint my curb,” and we would say, “We sure don’t expect you to give a donation if you don’t like it.”

If the exchange escalated to red alert the citizen watchdog would say, “I’m calling (called) the police,” and make a huffy retreat to the house. As we picked up our paint gear and faded away we would call out, “We respect your opinion, and we’re sorry you’re unhappy.” Once safely out of view we would jump in the car and make a quick exit to a safely distant area.

Here comes the law

By today’s standards local policing in suburbia back then was a haphazard affair that mostly involved meandering cruising akin to the Good Humor ice cream guy, the main difference being that the town cop wasn’t flocked by kids. Sunglasses disguised boredom, and police radio chatter projected vigilance and authority. This was the mid-sixties and the suburbs were safely barricaded from the simmering cauldron of the core city. Speeding teens, stray dogs and reports of vandalism, fueled by cigarettes and caffeine, helped brunt the monotony. So a couple of peripatetic curb-painting college kids were often as close as the local cops would get to Al Capone.

Unavoidably we would sometimes encounter a police cruiser, usually by happenstance but sometimes because of a complaint. The car usually approached stealthily from the rear: A couple of tanned young guys hunched over curbs were inherently suspicious. When available, we’d buy a T-shirt sporting the local high school logo.

Although the police chiefs almost always told us to stop painting, they usually didn’t think to tell us to stop collecting. And of course, we never brought it up or showed them our flyer, so we figured we were good for one more warning. We didn’t start collecting until early evening, and by that time most chiefs and the office day shift were home, so if a citizen called the desk to inquire, the person answering was usually in the dark and would radio an officer to check us out. When we saw a police car pull up we’d allay suspicion by strolling up and initiating a friendly conversation.

“Hello, officer.”

“What are you boys up to?”

“Oh, we’re accepting donations from people for addresses we painted on their curbs. Maybe you noticed them when you drove up the block.”

More often than not, after we explained what we were doing, the police officer would be agreeable, sometimes even friendly. But it was very rare for him to give us a green light. We were always deferential and learned to never argue; instead we would act mildly surprised that there was a problem, since other cities liked it, and ask if we could visit with the chief. This offer was crucial to erasing any suspicion of a scam.

Nevertheless on occasion the officer insisted that we check in with the police chief. If we did meet with the chief he would tell us we needed approval from the city council. We would respond, “Okay, thanks. When does your city council next meet? … Oh, okay, we’ll check with the clerk to see if we can get on the agenda.”

“By the way, I wish you boys luck. It’s a great idea. I like your T-shirt. You boys from round here?”

However, we soon learned that calling on the chief did not bear fruit, and we would not follow up. But the gesture erased any doubt of our legitimacy and good intentions.

However, if the officer was aware that we’d been told to stop, the conversation would go more like this:

“Hello, officer.”

“I got a complaint that you boys visited with the chief, and he told you to stop”.

“Yes, sir. The chief told us to stop painting, so we’re just accepting donations from houses we’ve already painted.”

“Well, go ahead and finish the houses you’ve already painted.”

“Thank you, officer. We definitely won’t paint any more curbs in (community).” (Whew!)

Or

“Well, I’m telling you to quit collecting.”

“Yes, sir.” (Damn! End of the line.)

House calls

Imagine this. Back in the mid-sixties most families actually had dinner together at home. Kids’ diversions were minimal. TV was the main family magnet, and the main distraction was siblings feuding over access to the phone. Furthermore, think of this: There was no cellphone, no voice mail and no caller I.D. Mom was bustling in the kitchen while Dad kicked back in his easy chair with a cigarette and beverage of choice.

So starting at 6 o’clock we would launch our foray into suburbia. Our goal was to each collect 100 houses an evening, so we had to move briskly. We kept a notebook of houses where nobody was home so we could return to collect later.

We would casually amble up to the door and knock lightly. This usually set off the dog alarm, and it was a challenge to talk above the yapping din.

Dad would usually be the first to hear the knock and would call out to Mom or one of the kids to answer the door. “Harriet, there’s some guy at the door. See what he wants.” So most often Harriet answered the door donning an apron and a smile.

Whoever greeted us, we would turn on the charm. As the door opened we’d just happen to be looking down the block with a wad of one-dollar bills in our left hand, forcing the greeter to glance down at the bills as we pivoted our head front and center with a nod and a smile. This tactic was crucial because back then most people would otherwise give us a couple of quarters. But seeing those bills in hand sent a message: Don’t be a cheapskate; look what your neighbors are giving.

“Hello, we’re the college students who painted your house number on your curb.”

“Ozzie, this is one of the college students who painted our house number on our curb. There’s no charge, but he’ll accept donations.”

“Oh. Well, you take care of it.”

Harriet would then ask. “What are they giving?”

“Well, most of your neighbors are giving a dollar, but some give more.”

“Oh. I think it’s a good idea. Ozzie, do you have a dollar bill.”

As we took the donation in hand we would say, “Thank you very much for your donation. It will help people find your house, especially at night.” Then we would jog across their lawn to the next house.

Occasionally a person—almost always a man—would say, “I don’t want it on my curb. Take it off!” This was problematic, and our response was, “Well, your neighbors really like it, but sure, we’ll do that tomorrow.” We’d jot down the address in our notebook with an asterisk and make sure we returned to honor our pledge, lest the crank call the police.

True to our word, we’d return the next day and apply industrial paint remover that steamed and fizzled as we poured it on the paint, following up with a stiff wire brush. My eyes would water and I’d go into sneezing convulsions. Agent Orange was probably its main ingredient.

Move over James Dean

Banned by Des Moines and weary of dodging the law in outlying suburbs, it was time to move on to greener pastures. Fueled by the visions of Kerouac and the TV smash series Route 66 we decided it was time to hitch our wagon. It was still early June and summer was ahead of us: two young studs heading down the open road, as Chuck Berry put it, “with no particular place to go.” Sunglasses perched above a cocky smirk, elbows draped out the car window, flicking cigarettes at stoplights as we winked at prospective babes. The ultimate cool. How could we lose?

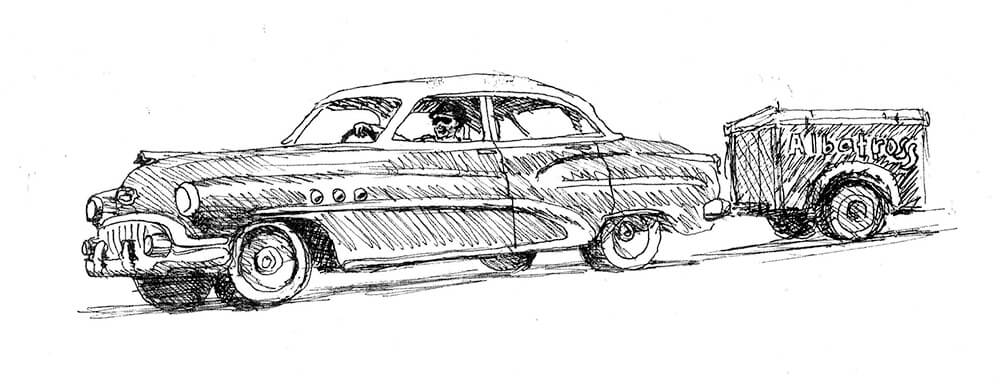

But, truth be known, we were at one huge disadvantage. Todd and Buzz cruised in a Corvette while we sported a 1952 Dynaflow Buick (nicknamed “Dynaflush” because when pressed over 60 mph the flow would turn into a lavatory flush), a miniature Sherman tank that got four miles to the gallon and could take on a semi-truck. Add to that our ramshackle two-wheeled wooden trailer, the Albatross, and we looked more like the Beverly Hillbillies than Smooth Dogs. We knew we’d be hard pressed to get a second look from even the most desperate of girls.

Hitting the road

We were infected with the unbridled optimism and fever that only youth can feel as we looked ahead to hitting the open road. Looking back I don’t recall what I was thinking—if I was thinking at all. Now 75, the prospect of such escapade would only occur under delirium. I understand what was going through my parents’ minds back then. Where we saw adventure and limitless opportunity, they saw risk and uncertainty.

As we were loading our paint supplies and camping gear into the Albatross, our neighbor Clyde Anderson strolled over to ask what in the world we were doing. We enthusiastically explained the drama that lay ahead. He asked where we were going, and we said anywhere and everywhere. He gave us a puzzled look and tilted his head as he surveyed our funky trailer, then stared at both us with a look of utter disbelief. He didn’t say anything. He just walked away.

A half hour later Mom came out and said, “Norman, Clyde just called. He thinks you boys need to see a psychiatrist. Something about a hare-brained fantasy.” Then Dad came out pensively puffing on his pipe and scratching his bald head, which he was prone to do when perplexed. As an astronomy professor he could more easily contemplate the cosmos than us embarking on such an adventure. His only comment was, “I hope you boys have liability insurance on that trailer. It’s pretty rickety, and the wheels look like they could disengage at any minute.”

The next morning I said goodbye to my folks. They just stood in the driveway with a look of sad bewilderment and timidly waved as I drove away. When I pulled into Mark’s driveway his parents and several neighbors were milling around in the yard. His father, a Protestant preacher, rolled his eyes and shook his head as he looked skyward and mumbled something about the lord delivering us from evil and flanking our sides on our journey. His mother muttered something about watching out for loose girls. Mark assured her that we would keep our pants zipped.

Kansas City here we come

“I’m going to Kansas City, Kansas City here I come …

They got some crazy lil’ women there and I’m gonna get me one.”

~ Wilbert Harrison, 1959.

Mark and I had sparred a bit about where to head. He favored going east … Chicago … Detroit … Cleveland … New York … Philly … D.C. I argued for South to Southwest … bounce our way to Houston and then meander west to the Golden State … then back east through Colorado. For once I prevailed. Being a weather geek I argued that we’d have too much idle time sitting out rainy days if we went east. So off we headed down Highway 69 to Kansas City.

Tooling down the highway in the confines of an old Buick can turn a couple of college guys into Siamese fighting fish. What starts out with a little pin pricks can soon escalate to poison ivy. It took about an hour for this to happen. I had to admit that Mark had a sweet melodic voice and some talent. He had played a major role in a number of musical productions in high school and most recently at Drake in South Pacific. What started as a hum soon became song. By the third time I’d heard “I’m gonna wash that girl right out of my hair” I was pulling my own hair. Mark was Rogers and Hammerstein; I was The Rolling Stones. This portended a long hot summer together.

“Hey Mark, could you tone it down a little?”

“Why? At least I can sing. You have a voice like a frog.”

I retaliated by launching into the Trashmen’s “Surfin’ Bird.” “Well a’ everybody’s heard about the bird … the bird, bird, bird, the bird is the word. Well the bird, bird, bird, the bird is the word. Well a’ don’t you know about the bird? Everybody knows that the bird is the word! A pappa moomamowwow, moomamawow”

“Stop! You’re driving me crazy!”

This went on for about five minutes before we paused, stared at each other, and lapsed into convulsive laughter. Like two boxers bloodied and knocked semi-conscious, we declared a truce and settled on the radio.

The askie monster

We arrived in Kansas City late morning and began driving around suburban neighborhoods scouting for fertile curbs. To our dismay we discovered that only a few scattered curbs had been painted. This was our first encounter with whom we dubbed the Askie Monster, a curb painter who had asked permission first, soliciting donations or charging a set fee.

Askie became our nemesis for the rest of the summer. If we followed his footsteps and blitzed a neighborhood we would incur the wrath of those who had declined his pitch. We would be greeted like the Fuller Brush Man.

It was now late in the afternoon and we’d worked up a sweat so we decided to shower at the downtown YMCA. We couldn’t find a parking spot to save our souls. Mark spotted a yellow curb loading zone and said, “What the hell, we can be back in 20 minutes.” It felt good to spruce up, but when we returned the car was being hitched up to a tow truck and there was a $20 ticket on the windshield. $20 tickets were unheard of back then except apparently in Kansas City during rush hour. The driver looked to be half gorilla and didn’t take kindly to us. Mark started to argue but I stepped in and handed him a ten spot. He mumbled something about damn kids but unhitched the chain. We decided KC was going to be a bust and that we needed to move on.

Countryside

Rebuffed in Kansas City we headed west across the Wide Missouri to Kansas. As would play out throughout the duration of the summer our approach to finding fertile ground was random meandering, pure happenstance. We strayed into the tiny suburb of Countryside, a satellite of Mission, Kansas. The curbs were ripe for painting and the homes classic late fifties ranch.

It was midafternoon by the time we unloaded and prepped Stanley to begin painting, and things weren’t boding well. Apparently Stanley didn’t like bumping along in a trailer, and we wrestled for more than a half hour trying to start him up. He would chug and sputter but successfully rebelled despite our coaxing.

A gaunt gray-haired elderly woman with a menacing scowl wandered up to us. She looked like she’d just choked on a pickle. “What on earth are you boys doing?!”

“Oh, hi ma’am. We’re going to be painting house numbers on curbs as a service to Countryside.”

“What is that monstrosity?!” She glared at us suspiciously and said, “We here in Countryside don’t like our curbs painted. I’m calling the police.” We knew we had to git while the gittin’ was good. As she walked back into her house we made a snap decision: Leave Stanley in her driveway and hightail it to Wichita.

We’d blown another day, and I was starting to have second thoughts about venturing farther down the road, but Mark was undeterred. We had a couple hundred bucks, and he argued that it would last us a week. I said, “Yeah, but I don’t want to be destitute in Dallas and have to wire my folks for gas money to get home.”

As we drove toward Wichita in the late afternoon, the Flint Hills unfolded in lush June splendor, an emerald waving sea of big bluestem and switchgrass. The waning sun cast an orange glow on the prairie, and as nightfall approached sleepy fireflies awoke to illuminate the land. Probably a hundred miles to the south giant anvil thunderheads put on a dizzying light show. Some enchanted evening.

As we neared Wichita we pulled off a side road, unrolled our sleeping bags and sacked out on a grassy patch. We awoke at the crack of dawn and gorged ourselves with a ranch-hand’s breakfast at Maude’s Café. We were psyched to hit the curbs

Wichita

Our plan for the summer was to scope out the local college nearest the suburb we would be painting for showering and lodging. Our first choice was a SAE fraternity house, if one existed. Fraternities were always our first option because we could usually anticipate some shared social revelry. If no fraternity was on campus we’d check at the local college men’s dormitory and offer to pay for each night of our stay. There were always beds available, and the dorm superintendent almost always gave us a room for free. A local campground was our third option and—try fathoming this in today’s world—if none of these options panned out we’d find a backroad and flop down in our sleeping bags near the car.

Our buckets of white paint were useless without Stanley, so we needed to invest in quick-drying white spray paint. We found a paint store and bought a 24-pack of spray cans to accompany our black paint.

Wichita was our turning point. We lucked out to find that the fraternity house at Wichita State University was open for the summer with plenty of available beds. The “brothers” extended us a warm welcome… into the night.

We hit the curbs the next morning after hiring a couple of 10-year-old kids to place fliers in every front screen door for two cents a house. This was our first full day since hitting the road, and we had yet to hit our full stride but were getting the hang of it.

We managed to paint about 150 curbs, and after showering at the fraternity we put on our casual best togs, grabbed a burger and fries, and started knocking on doors. Things went smoothly and most people greeted us warmly. Surprisingly, there were no hassles. And another thing that is hard to fathom in today’s world is that we would be jogging across lawns and calling on houses at twilight with nary any suspicion.

At the end of the evening we nabbed about $97. We wrote down the addresses of houses where nobody was home in our pocket notebook so we could check back in the future. As we became more proficient at painting we discovered that if we could finish painting by early afternoon we could clean up and follow up on the “not-homes” address list from previous days before making our nightly rounds. The not-homes list was also a crucial fallback if we got rained out from painting on a particular day.

After several days in Wichita wanderlust pulled us southward. We stopped in Ardmore, Oklahoma, and stayed with Gray Richards, a fraternity brother, for several days. Ardmore was a small city but had a subdivision with several hundred nice ranch homes. Gray’s dad was the local banker and city king-maker: What he said went. He called the mayor who in turn called the police chief, and we were granted immediate permission to paint and collect. It was in Ardmore that for the first time something became glaringly apparent: We were Yankees. At just about every house people would ask, “Where y’all from? to which we would reply, “Drake University.”

“Oh, Duke! Isn’t that an Ivy League School? They play pretty good basketball there.” We didn’t bother to clarify.

Most people were friendly albeit a bit suspicious of our northern accent. Whenever we could, we would say we were staying at Gray Richard’s house, and the bills would flow.

Punch-counterpunch

It only took two days to exhaust our curbs in Ardmore, and we were off to Dallas. Mark and I were constantly scheming to out-prank each other. Bars were the most obliging venue, but any place or situation was fair game. When meeting a new acquaintance the trick was to get the jump on the other guy. I could always tell with Mark: His eyes would get a mischievous glint and he couldn’t hide a subtle smirk. And he had an uncanny knack for sizing up a ripe opportunity and beating me to the punch.

Walking into Wrong Daddy’s Saloon, extending his hand to the most obvious redneck bruiser sitting at the bar: “Hi, I’m Mark Thompson. My friend Norm and I are just passing through on our way to Dallas. Can I buy you a beer? Norm is a civil rights activist and pacifist.”

I had about ten seconds to defuse such an encounter or be flattened, grinning, “Nah, Mark’s putting you on. I’m a George Wallace supporter. Got no use for those agitators.”

Or, “Hi, I’m Mark Thompson and this is my friend Norm Riggs. We’re just passing through. Can I buy you a beer?” After some casual conversation Mark would out of the blue bring up, “Norm’s a butterfly collector and plays the piccolo.” This always triggered a wary stare and backpedaling, but at least it didn’t provoke a violent response.

Mark was a good-looking guy and well aware of it. He was proud of his deep olive tan and comported himself with cool self-assurance. If I got out in front of him my line would be, “Hi, I’m Norm Riggs and this is my friend Whitey Thompson. We’re just passing through. Can I buy you a beer?”

“‘Whitey,’ how the hell did you get that name? You look more like a Mexican to me.”

This always knocked Mark off balance, but before he could respond I’d break in, “Sorry Mark,” then turn to the redneck, “I’m kinda absent-minded. I’m good friends with Mark’s older brother who has premature white hair…”

Penny Lane

“Penny Lane is in my ears and in my eyes

There beneath the blue suburban skies

I sit, and meanwhile back

Penny Lane is in my ears and in my eyes

There beneath the blue suburban eyes.”

~ The Beatles, 1967

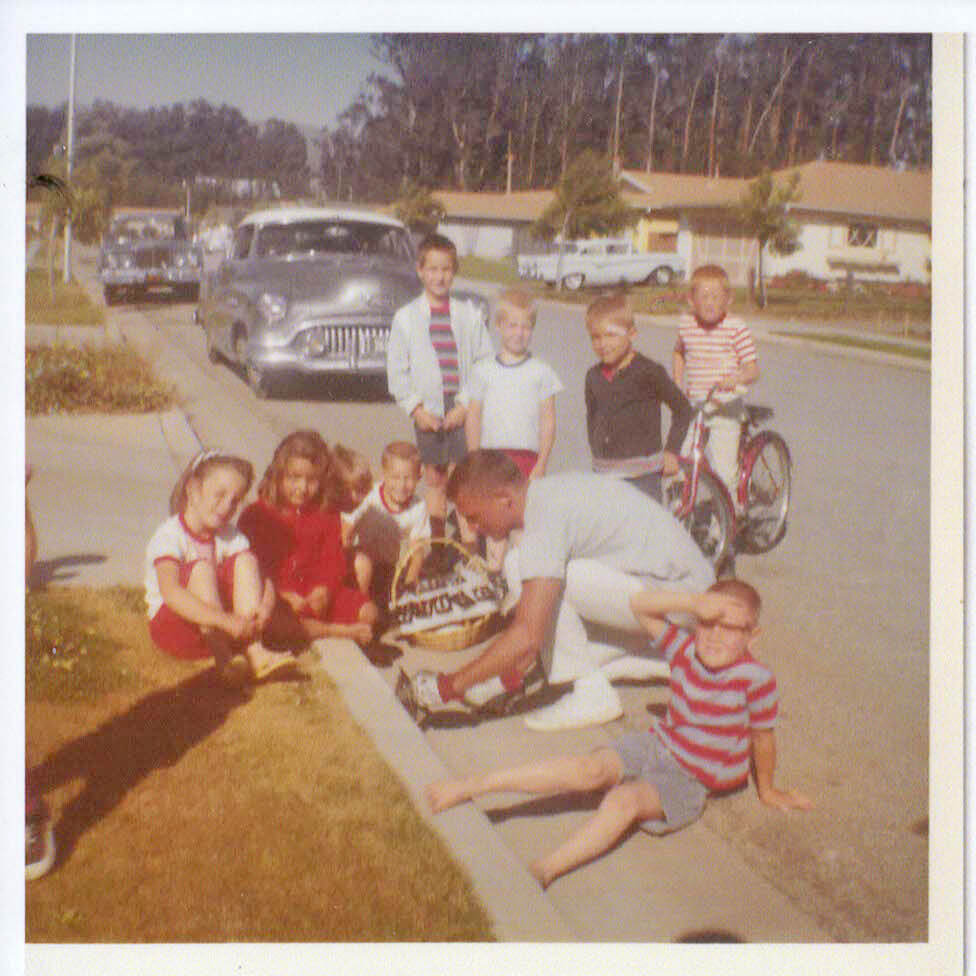

After painting curbs in the Metro Des Moines suburbs and now heading for Texas, Mark and I had become windshield sociologists of sorts. We could make some safe generalizations about suburban America in 1964 when it was at its unvarying pinnacle.

At the risk of oversimplifying, America could be broken down into three big pieces: urban, rural and suburban. Urban and rural could further be broken down into a rich complex amalgam of pieces; suburbia was basically one big homogeneous chunk. The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, Leave it to Beaver, and Father Knows Best weren’t all fiction. They personified the American Dream. We saw it every evening when we knocked on doors.

Here were some things we observed:

We literally did not see one African American, Latino or Asian person heading a household. We saw plenty of minorities during the day mowing lawns, house cleaning, child sitting, roofing and doing carpentry work, but they vanished at the end of the workday. Redlining effectively erected the wall of segregation.

Houses pretty much looked the same. Most were ranch or split level, and a few sported pillars to project the illusion of a southern mansion. A two-car garage was an imperative, as was a picture window in front. The front porch was modest because outdoor activity revolved around the back deck or patio.

Two cars were now the rule instead of the exception.

Above ground swimming pools flaunted success.

Most mothers were still stay-at-home during the day watching their kids.

Grill smoke permeated the air at dusk.

Adults were not commonly seen in the front yard unless mowing the yard or washing the car; the backyard was where the action was.

Kids were highly visible in the front yards with boys playing catch or shooting baskets on portable hoops astride the driveway or racing down the street popping wheelies with their Schwinn Jaguars or Corvettes, some with candy cigarettes hanging out of their mouths. Girls would be playing jacks, hopscotch, and clustering and giggling.

Fertilizers and pesticides along with sprinklers ensured a lush green lawn.

Most houses had dogs, and most dogs were small and yappy.

Life, at least on the surface, was good. People felt safe, drugs were nonexistent, and occasional alcohol consumption by teens was more of a mischievous caper than common indulgence.

Looking back, there was an innocence that seems idyllic today. I lived it as a suburban kid, basically free from fear and excessive academic pressure, with plenty of time to hang out with the neighborhood gang, get into mischief and not be shuttled around to endless activities. Perhaps I’m romanticizing things a bit, but sterile as it was, on balance I’m glad I grew up in suburban America when I did.

Waco

Close Encounters

“Carefree highway, let me slip away

Slip away on you.”

~ Gordon Lightfoot, 1974

The thing about Mark and me was that we were more like lost puppies than migrating birds: We frolicked our way south and then west to California on whimsical impulse with no particular destination in mind beyond the next day or two. Should we head west through Austin and San Anton or south towards Houston? The coin flipped heads, so Houston it was.

As we rambled south in search of virgin curbs we made a one-day stop in Waco, perhaps the most unremarkable city in Texas. We were 10 days into of our adventure and hadn’t phoned home for a week. Back then cell phones were nonexistent and navigating a pay phone was a clumsy affair. Encumbered by a handful of change we’d have to feed them into the phone box to get connected, then feed more coins every few minutes – prompted by the operator – if we wanted to continue to talk.

Today’s helicopter parents would totally freak out at how we traveled incommunicado for days on end, but that was the way it was back then. Communication was sporadic. We’d mail a postcard every three or four days and call about every two weeks. If an emergency should arise our parents would begin by contacting the police in the last city they were aware of. If that didn’t pan out they would need to call the state highway patrol.

We decided to make Mondays our accounting and banking day when we’d count and split our week’s haul and send a cashier check to our parents to be deposited in our bank saving account. I relished sending my share home, but Mark’s accounting tutorials were an excruciating ordeal. He had just finished a class on small business accounting and set up an elaborate labyrinth of boxes in columns and rows that meant nothing to me. His weekly summation would drone on for half an hour and was best suited to an insomniac ward. Nevertheless I endured his ritual for the duration of the summer. He said we needed it for tax purposes, but I reminded him that he was adamant about not leaving a traceable paper trail because we didn’t want to pay taxes to the IRS. Didn’t matter. He loved caressing and stacking money and bracketing it as tangible proof of our haul.

We kept a heavy metal cash box hidden under the spare tire wheel well in our trunk, but it could not accommodate the mountains of coins we’d accumulate, so we dumped them in a gym bag. It caused quite a stir when we’d stroll into a bank and hand the teller a 40-pound bag of loose change.

My 10-day share was over $700. When I next talked to Dad he said he’d stopped at our tiny branch bank and was greeted by its emperor and sole employee, James D. Boddagard III, aka Mr. Whipple to us kids. Boddagard always conducted himself with erect aplomb. Dad told me he carefully studied the check and shook his head with a sputtering cluck, saying, “My word, Norman is a very enterprising young man. How does he earn all that money?” I could just imagine my dad, an astronomy professor, trying to explain the art of curb painting to a financial mannequin.

It was in Waco that I had my first close encounter of many that would follow. We were blithely painting along when I noticed a couple of bare chested hulks in shorts pumping iron inside an open garage door wearing University of Texas football shorts. They took a bead on me, strolled up, and asked, “What the hell are you doin’?”

I gave them the same spiel I used with the cops. It didn’t go over well.

“You a Yankee?”

“Yeah, but I’ve always wanted to see Texas.”

Meanwhile Mark, trailing me and sensing imminent danger, wisely went into a freeze frame a half block downwind. Better one guy in the hospital than two.

Sandwiched between them, they started pushing me back and forth. Now I’m not a meek guy, but I value my life. The one bruiser put his thumb under my chin, lifted it up and glared down at me. “What college you goin’ to?” “Drake.” “Drake? Never heard of it. Sounds like a school for wimps. Whaddaya studying?”

The next five seconds probably spared me that trip to the hospital.

“I’m majoring in religion.”

“Huh. What religion?”

“All religions, but I’m Baptist.”

“Baptist … hey, alright! Jamie and me are Baptist. I didn’t know there were Baptists up north.”

Suddenly the conversation turned congenial. They told me they played football for the University of Texas. I couldn’t stand the University of Texas football program, but I knew a little about it. They had won the national championship the year before. I dropped the names of Coach Darrell Royal and Tommy Nobis, first team All-American linebacker and college football player of the year.

Mark sensed the change of weather and walked up. “Mark,” I said, “Meet Jamie and Bobby Lee. They play football for the Texas Longhorns. I was just telling them that I’m majoring in religion at Drake.” Mark couldn’t hold back a slight smirk but got the message. He extended his hand and affirmed his respect for Longhorn football. He added that he hated their arch enemy, the University of Oklahoma Boomer Sooners.

Jamie and Bobby Lee told us to hold on, and Bobby Lee went inside to fetch four Cokes. We chatted like fast friends for about ten minutes, shook hands, and continued painting up the street, calling back “Hook ‘em Horns!”

Lesson learned. Always know and be a fan of the local sports scene. And when in the South always be a believer.

Houston

Streetfight

“Dear old southland with his dreamy songs

Takes me back there where I belong

How I’d love to be in my mammy’s arms

When it’s sleepy time way down south.”

~ “When it’s Sleepy Time Down South,” Louis Armstrong, 1931

As we neared Houston and the Gulf we could feel the onslaught of stifling heat, the kind of suffocating heat that clogs your pores and brings on wilt: a veritable steam bath with temperatures and humidity both in the high 90s with nary a breeze. I’d never ventured south of Arkansas but could now relate to Louie’s lyrics. No wonder people move ‘possum slow come summer down South. Even sitting couldn’t spell relief without a fan.

Metropolitan Houston was unlike any other American city we would see that summer in that it wasn’t ringed by suburbs. The City of Houston had annexed all of Harris County, and while there were distinct suburban neighborhoods the police were all under the jurisdiction of the city. As we scouted the area we found scattered areas that had been peppered by the Askie Monster and others that were virgin. It was getting late so instead of painting we decided to check out lodging around the University of Houston and rang the bell of a stately white antebellum sorority house, pillars, magnolias and all. A svelte southern belle answered and scanned us cautiously. She was a tall brunette with alabaster skin, green eyes and an air of southern aristocracy, legitimately beautiful. She eyed us cautiously and minced no words: “We’re not buying anything.”

She started to close the door when we pleaded, “We’re just looking for the SAE house.” A complete one-eighty. “Oh, you guys SAE’s? Hi, my name’s Harper. Follow me. You sure aren’t from around here. Where’s home?”

We explained and she ushered us into an entertainment room where about a dozen girls were watching TV. “Hey, y’all, meet Mark and Norm. They’re visiting from Iowa and looking for the SAE house.” One of the girls asked us what we were doing in Houston, and we gave a brief rundown.

Afterwards another girl – regrettably not the pick of the litter – winked and said, “You guys are kinda cute. Iowa … is that where they have good skiing and grow lots of potatoes?”

Idaho, Iowa, Ohio, they’re all one geographic blur in a lot of people’s minds. I replied, “Skiing, mountains, potatoes—you must be thinking of Ohio?”

The SAE house turned out to be only a few blocks away. We checked in, and there was no housemother and only a few guys hanging around for the summer. They were under 21 and received us warmly when we offered to buy a few six-packs.

The next morning we awoke early and toiled in the Amazonian heat, managing to paint 250 curbs. Thankfully no beady-eyed watchdogs or cops hassled us, and we anticipated a bountiful evening. The police were nonchalant and some would pass and wave. We even had friendly chats with a few, and one sergeant offered to take us fishing. We concluded that they liked the idea of metallic addresses, and patrolling a huge city they had bigger fish to fry.

Collecting that evening our optimism was shattered on the third block where we were politely informed that, “Oh, your two other college friends already collected from us.”

“Huh? What did they look like?” “Well, they looked younger. More like high school kids.”

It took a nanosecond to put things together. Punk imposters! My immediate reaction was borderline homicidal, with confrontation the only option.

We started cruising the neighborhood and before long spotted two kids standing on a porch conversing with a lady. We waited till they were moving to the next house and summoned them over.

“Hey, what gives!?”

“Whaddaya mean, ‘what gives’?”

“You punks know what we mean. You’ve been collecting our curb painting donations.”

“So?”

“So get your butts out of our neighborhood and hand over what you’ve collected!”

At that point our best option was to get tough and shake ‘em down. They were starting to look like scared rabbits and could bolt at any second. If they ran it would involve a tackle and a tussle. And they had one buddy we didn’t want to mess with: a lip-curling Dalmatian starting to drool.

Mark looked at me, frowned, and shook his head. He asked them, “How many blocks you punks collected?” “Guess, big man.”

Just then providence cruised by in the form of a police cruiser. Never in our wildest curb painting dreams could we ever imagine flagging down a cop. But we did. The officer rolled down his window, exhaled blue smoke, and asked, “What’s the problem?”

We explained our laudable neighborhood service project and handed him a flier. To our great relief he told us he’d noticed the addresses and liked the idea. He then glared at the boys and said, “You boys are thieves. I could take you down to the station, but instead I want to talk to your parents.”

They began to quake and shuffle. “We’re really sorry officer! We’ll give them back the money. Just don’t tell our dads.”

They handed over their collection bounty and, Dalmatian astride, walked away tucking their collective tails. We heard the cop call out “And put that dog on a leash!”

Justice had prevailed.

Westward ho

El Paso

After painting four days in Houston we started California dreamin’. We were totally drained by Houston’s relentless heat and humidity, and The Beach Boys were echoing in our ears. We decided to make a 750-mile beeline for El Paso.

The landscape gradually changed from lush Dixie to moonscape West. Jack pines, live oak and Spanish moss gave way to prairie and eventually to cacti and tumbleweeds; playful dust devils danced across the vast desert floor; turkey vultures glided effortlessly on thermal updrafts. Peering down the ribbon of highway we could see a shimmering mirage of water in the distance, just beyond the reflection of the blinding desert sun.

The sun gave way to nightfall. There’s something enchanting and mystical about driving across the desert at night: a beautiful and profound sense of emptiness and loneliness, of finiteness. A serene silence worthy of drawing an atheist to God.

We had the highway virtually to ourselves. The night sky loomed like a brilliant planetarium, crystalline air devoid of human light; distant purple mountains silhouetted against a limitless horizon. Our only companions were a few skittish antelopes and occasional coyotes nonchalantly standing in the road, their eyes glowing amber as we approached, then loping off casting a casual backward glance.

We arrived in El Paso at dawn and checked out housing at Texas Western University (now The University of Texas at El Paso), finding a modern dormitory near campus. A graduate student was the summer manager and told us there were plenty of vacant rooms and to just take one for free.

El Paso’s climate was a welcome reprieve from Houston’s dripping humidity. The temperature topped 100 degrees every day, but it was a dry heat and we hardly broke a sweat. And nights were pleasant. After five days of painting we decided it was time to pull up stakes and keep heading west toward California.

Phoenix

It was early July when we left El Paso and headed for Phoenix and into the headwinds of a record heat wave, with temperatures approaching 120. It was so hot at Sky Harbor International Airport that airplanes were grounded, but that didn’t stop us from painting. We wore skimpy shorts and didn’t even bother with sun lotion. The heat was so desiccating that we were each drinking a gallon of water every hour but with the absence of humidity didn’t even break a sweat. We were perfect candidates for a heat stroke.

Mark had brown hair, brown eyes and olive skin that turned copper luster. Being of northern European blood, I wasn’t so lucky. My complexion was a hybrid brown, red and lizard since I had ongoing peeling and flaking. As a result I’ve been a dermatologist’s dream. Much like smoking, I can’t believe how oblivious I was to the warnings that were starting to come out about sun protection against skin cancer. But at 21 time was on my side, or so I thought.

Phoenix was the cornucopia of curbdom, being ringed by mostly virgin suburbs: Mesa, Tempe, Chandler, Scottsdale, Paradise Valley and Glendale. It was fertile ground for guerrilla curbfare because, with this many cities, we could strike, fade away until any tempest blew over and return several days later to collect. The law hounds were trying to sniff us out, but we were always one step ahead of them since, thankfully, watchdogs didn’t just call the police; first they told us they were going to call the police. Adios.

We encountered a disproportionate number of disagreeable people. I think in part it was largely the weather that was causing tempers to flare. And Barry Goldwater, their native son running for president, had the suburbs in a partisan lather. Seemed like every other yard had a Goldwater sign. This was tough on Mark and me, being diehard Democrats. We tried not to engage in political discussions because it was distasteful and slowed us down dramatically. I developed a line whenever I ran into an argumentative proselytizer, responding,

“Yes, I like Larry Goldwater.”

“That’s Barry Goldwater!”

“Oh, I get confused. I’m not much into politics. Anyway, nice chatting. I need to move on.”

We were hauling in a lot of dough, and Mark was starting to strut his stuff. But our traveling hillbilly roadshow didn’t enhance his image: a 1952 Buick emitting blue smoke with the Albatross in tow, rattling and swaying like a drunk. Definitely not cool.

Lo and behold what should jump out at him in the middle of a lawn but a 1952 MG-TD. It was a deep chestnut brown with matching leather interior, his for $900. It was love at first sight, and I knew what he was thinking: “Let Norm clunk along as he will; I will always be a length behind looking like I just drove over from Beverly Hills.” Maps weren’t his thing, and I had to be in front because he never knew where he was going.

He was fairly gloating over his shrewd purchase and took me on a jaunty tour. We pulled into an A&W drive-in featuring speaker phones and girls on roller skates and placed an order for chili dogs, onion rings, and 24-ounce frosted mugs of root beer. A spritely teenage blond whizzed up with our lunch and commented, “What a cute little Triumph.”

Mark hunched his shoulders and grimaced. He didn’t take kindly to her misidentification. “Triumph! That’s an insult. Would you know the difference between a Cadillac and a Nash Rambler?” He proceeded to give her a spirited lecture on the distinctive history and merits of his hallowed new prize.

I winked at her and said, “He thinks he just bought a Rolls Royce.” Mark didn’t see the humor, and I made a quick note of his sensitivity. From that point on whenever we met a new acquaintance I’d point to his MG and say, Check out my friend Mark’s cool Triumph” and watch his pained reaction with glee. Actually, I think he rather enjoyed the confusion because it gave him an opportunity to extol the virtues of his ego on wheels.

Famed and Framed

We were really cruisin’. We’d been in Phoenix for almost a week and each pulling down close to $100 a day, big money for a couple of vagabond college boys.

It was in Glendale on the fifth day that the lure of flattery trumped our better judgment. I knocked on the door and was greeted by this genial 40-something man in shorts and a T-shirt. I gave him my spiel, and he perked up and invited me in to tell him more about our summer adventure. He told me he was a feature writer for the Phoenix Sun and this would make a good story. Mark was across the street and I whistled him over.

We retraced our footsteps for him from the idea’s inception to his house. He took fastidious notes and after an hour asked if we would be willing to pose for some photos. Our egos were pulsating so of course we consented. His article came out in the Sunday Sun, and we beamed when we saw our mugs prominently displayed on the front page of the features section along with a flattering tribute to our entrepreneurial saga.

The bad news was that we were no longer phantoms. We were two identified college guys from Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, on the lam.

The day after the Sunday article the paper ran a response from the Metropolitan Police Association warning people that what we were doing was illegal defacing of public property, and if spotted the police should be notified immediately.

It was time to get out of Dodge so we headed for Las Vegas, still a small town of 120,000 but with a glamorous pull like Los Angeles or Miami. Today it has swelled to over two million. We found virgin curbs but there was an eerie shadow cast over the total absence of even one painted curb. Apparently this town aggressively pursued the faintest whiff of shysterism, and we were fringe shysters. (I looked up the German origin of shyster—“scheiss”—and found it meant defecator. Now I know what my rancher grandfather meant when he’d mutter “shyster” after a business transaction. None of his neighbors had clean boots.)

California here we come.

California dreamin’

Now that we were a two-car team we needed a plan to reunite if we got separated. We had an agreement that when that happened we would reconnect at the local city hall. We had some time to kill in Las Vegas, since it was mid-July and we wanted to hold off until nightfall before crossing the scorching Mojave Desert to reach our next destination: Santa Barbara, California.

I parked the Buick and Albatross at a shopping center and hopped in the MG for a tour of The Strip. After taking in a burlesque show and doing a little penny ante gambling we were ready to hit the road. I envied Mark driving a sports car with the top down and the breeze in his face while I rumbled along encased in the Buick.

The drive to Santa Barbara was almost 400 miles of sparsely traveled meandering highways, disconnected ribbons fading into the nightscape. At one stretch we drove for almost two hours without seeing a headlight. The Mojave is the driest and most inhospitable desert in North America, and when driving across it at night its harshness can cast an eerie spell. As we drove into its heart we noticed an army of Joshua trees silhouetted against the intense light of a full moon. Joshua trees are the most humanoid tree in the plant world. Actually not trees, they are a member of the yucca family that can reach a height of 40 feet. They were so named by Mormon settlers who likened their twisted animated shapes to the prophet Joshua raising his hands to the lord.

The infinite blackness was starting to take its toll. About two in the morning I was seeing double. I pulled over and told Mark I was seeing apparitions loom on the highway and needed to catch some shuteye. Mark wanted to barrel ahead to Santa Barbara, so I told him to go ahead, that I’d meet him at the post office the next morning. He called me a short-hitter but reluctantly decided to join me. We pulled off a dusty side road and stretched out our sleeping bags in a sandy open patch. Much to our delight we were serenaded by an encircling band of coyotes who seemed to resent our encroachment. Sweet music to doze off by.

Our dozing never materialized: I was laying on my back mesmerized by a cosmic display of the heavens, air so clear that stars on the horizon winked boldly, when I heard a faint rustling several yards from my sleeping bag. I grabbed my flashlight and took a bead. A snake was slithering in my direction. Not a small snake but a big mutha, looked to be a good five-feet long. His eyes reflected as embers in the beam. I shrieked, “Snake!” and hurled a rock, which he obviously didn’t appreciate—he coiled and rattled like a swarm of locusts. I floundered out of my sleeping bag and made a beeline for the Buick. Mark was sound asleep but jolted into high gear when he heard the word “snake.” He had a phobia about snakes, and as I glanced back I became a believer in levitation.

He joined me in the Buick, and when we regained our bearings we decided it best to wait till dawn before safely retrieving our sleeping bags. Mark said he’d heard in cowboy lore that snakes sometimes sought out the warm cozy comfort of a sleeping bag and added that the Mojave rattlesnake delivered more toxic venom than any of his cousins. I dismissed this as an old wives’ tale.

Dawn arrived and we circled our bags, seeing no evidence of a snake other than some furrows in the sand. We gingerly massaged the bags and detected no suspicious lumps. Feeling none, we cautiously unzipped them and shook furiously. Good thing: A scorpion tumbled out of Mark’s bag and scurried into the sagebrush.

Mark cast me a piercing look. “Holy crap,” he said. “Never ever ever again will you catch me sleeping in the desert without a tent. In fact, not even in a tent. Creepy crawly things can always slither inside. From now on I make the call on where we sleep.”

The Mojave gradually gave way to the arid Central California Valley and then the San Joaquin Forest as we approached the San Ynez Mountains to the west, the last barrier to the hospitable Mediterranean city of Santa Barbara. As part of the California Coast Range they pose as a shield that in summer separates an oven from a refrigerator, with temperature differences that can exceed 40 degrees.

As we drove up toward the summit, chaparral and grasslands surrendered to live oak, bay laurel and coulter pines. When we reached the crest we parked our cars, scanned the vast horizon of the azure Pacific Ocean and breathed deep. The arid desert air was pushed back by a wave of cool, moist saline air, accompanied by the aromatic delight of pine tar and eucalyptus. After over a month of unremitting heat we were intoxicated.

Santa Cruz

It was mid-July when we arrived in Santa Cruz, a city of only 25,000, early in the morning after an all-night drive from Santa Barbara. Although dog-tired, we were immediately invigorated by its beauty. The city lies on the northern edge of Monterey Bay and is known for its moderate climate, redwoods, beaches, world-class boardwalk, alternative community lifestyles and socially liberal leanings. And to our glee, there was only scant evidence of Askie in the suburbs. We rubbed our palms in anticipation.

Our first task was to stake out lodging at the University of California, Santa Cruz. The campus, which is on a peninsula in the bay, is renowned for its Spanish architecture buildings and is a lush arboretum of coastal and subtropical trees. We were warmly greeted at the SAE house and told there were some available beds on a second floor dormer. The brothers were impressed by Mark’s MG-TD but asked that I park the Buick and Albatross in the back lot. The unspoken word was that my entourage would repel potential coeds.

We immediately set about painting and found the residents to be exceptionally generous, and surprisingly we got no grief from the police. We figured to spend at least a week there before moving on.

A skirmish with terror

On the fourth day we found virgin curbs in a fertile neighborhood and set about finding two young kids to leave slips in doors for two cents a house. (There were no child labor laws that covered the enterprise of curb painting.) We could almost always readily find kids in the age range of nine to 13 riding their bikes or playing in the front yard. But on this day nary a kid was to be found; it was Saturday morning, cartoon time in America.

After cruising up and down several blocks we spotted two little towheaded boys riding bikes and popping wheelies. We liked their spunk. We sized them up and figured they were only six or seven, way too young. But as we were ready to drive on one of the boy’s mother appeared at the front door. When she spotted the Buick and Albatross she walked up to inquire what we were up to. The little boys pedaled up to join in the conversation. After we explained, they excitedly waved their hands and pleaded to hire on. We told them we’d like to, but they were just too young and asked the mother if she knew of any other kids in the neighborhood who might be interested. She said offhand she didn’t but thought her son, Robbie, was up to the task and wanted him to develop a work ethic. We hesitated, but she assured us he could do the job and that she’d check with the other boy’s mother to see if it was okay for him to join the team. Robbie’s pal got the green light, and both mothers told the boys to stay with us and not run ahead. We were off and painting.

Things were going well the first three blocks when suddenly we heard a blood-curdling scream coming from around the corner. We looked up and noticed Robbie was nowhere in sight.

A chill of terror came over us, and we sprinted to the source. Robbie was lying limp on the ground while a diminutive man was frantically pulling a lunging, frothing Rottweiler, trying to drag the beast into his house. Robbie was no longer screaming and had gone into shock, twitching like a wounded sparrow.

It was immediately apparent that he had been mauled by the dog and had deep wounds and lacerations over his torso and one arm. Mark ran back to notify Robbie’s mother while I knelt over him, pulling off my T-shirt to staunch the bleeding. A wave of helplessness and suppressed panic swept over me as I yelled for help.

A woman immediately rushed out of a house across the street and gently brushed me aside and took over, explaining that she was a nurse. Within minutes several other neighbor women appeared, and one was carrying gauze and said she’d called an ambulance.

Robbie’s mother rushed to the scene and began gently caressing him while the nurse applied more gauze and cleansed the wounds, applying antiseptic. I was deeply touched to see what a mother’s touch can do to a terrified little child: he was still sporadically sobbing but was able to explain that the dog had torn its chain out of the ground.

The dog’s owner came out of the house and began sputtering in what sounded like Spanish but turned out to be Portuguese. He managed to convey that he was off work that day and he’d called his wife, who worked at a bank.

The ambulance arrived and Robbie’s mother accompanied him to the hospital. The police arrived shortly thereafter, and several neighbors told them they had been living in mortal fear of the dog and that this was an accident waiting to happen. The police assured them the dog would be euthanized.

Mark and I sped to the hospital emergency room and were told Robbie was in surgery with his mother at his side. Over an hour passed as we paced the ER awaiting word on his condition when his mother appeared. We quaked at the prospect of a tongue-lashing and possible law suit, but her demeanor was calm and reassuring. She said that it wasn’t our fault, that she had granted permission and emphasized to Robbie that he was to stay with us. She said he had some deep wounds but that his face and head had been spared, and the doctor’s prognosis was that he would only have minimal scars. The wounds were being stitched, and antibiotics should prevent infection. She was an amazingly composed and warm woman and looked us each in the eye before giving us a reassuring hug. My eyes welled up, and it was all I could do to hold my composure.

Robbie spent that night and part of the next day at the hospital before going home. We stopped to see him at the hospital, and despite being bandaged up to the hilt the little warrior was in good spirits and relishing the attention and sympathy. He was wearing his bandages as a badge of honor.

We checked back at his house several times over the next few days and gave him a police badge as a tribute to his valor. He beamed with pride.

While Robbie recovered quickly we didn’t do as well—we were haunted by what we had witnessed. The horror of the mauling scene was a recurring nightmare that I couldn’t shed or atone for. We had narrowly averted disaster, and my sense of security was shaken. To this point I had lived a charmed unscathed life in terms of avoiding tragedy, and I suddenly felt and understood vulnerability. It was a dark cloud that hovered over me. My only previous encounter with shock and intense grief was when I was eight years old and found my best friend, Pancho the pup, run over by a car.

After a while my anxiety began to ease, but the memory would never be erased. Caution was now in my veins, and I’d become an overnight adult. I realized that when we hired children we assumed a parental responsibility for their safety and welfare.